Abstract

Taking Secret Cinema as its site for analysis, this article engages with the question what is ludic at the cinema. Secret Cinema delivers live, immersive, participatory cinema-going experiences and is a complex interaction between film, game, theatre and social media. Through the expansion and reimagining of a film’s milieu in both virtual and real spaces, Secret Cinema experiences encourage spectatorial performativity and ludic participation. Through the use of multiple methods, this article presents the formation of a dramatic and playful community in which the impact of game cultures and a ludic aesthetic upon cinematic audience spectatorship is illuminated. Cross-disciplinary in its approach, this article connects the registers of both game and film studies in order to account for this emerging playful engagement with cinematic texts. Through its use of empirical methods, we move towards a fuller understanding of audience experience and affective engagement.

Keywords

Immersive cinema, Ludology, Secret Cinema, Dramatic Community, Play.

Introduction

Secret Cinema (SC) (2007-) launched in the UK with an immersive screening of Gus Van Sant’s Paranoid Park in a disused railway tunnel, and has since delivered numerous expanded cinematic experiences. SC addresses a growing demand for live, participatory and often visceral cinema-going experiences and is shaping a new and highly profitable event-led-distribution-model. Prometheus made more money as a SC event than at the IMAX premiere and Grand Budapest Hotel’s No1 box office position was largely attributable to the £1.1m generated by SC. These events have garnered a huge following of devotees who are willing to pay premium ticket prices to experience highly crafted and augmented collective viewing events around a particular feature film. The experiences have been marketed in a clandestine way via word of mouth and social media in which participants are instructed to ‘tell no one’. From the moment of the tickets purchase, audience members knowingly and complicitly enter an in-fiction space. Dramatic exposition is presented in social media spaces and audience members receive instructions to make preparations before attending the event, such as how to dress and what persona to adopt as part of the instantiation of the film. The interrogation of such a complex and multi-layered experience requires a multi-modal research design, and in this case will be underpinned by a synthesis of the critical concerns and insights of game studies and film studies. Through participant observation of one event by two researchers, a close textual and aesthetic analysis of the experience has been conducted by building on existing film studies conceptualizations. Drawing on the broad discipline of game studies and the centrality of play theory, an analysis of the affect of the experience has been enabled through qualitative questionnaires and interviews both before and after their experience with a randomly selected sample of seventy participants, who responded to a call for participation through social media channels.

A new cinematic game space

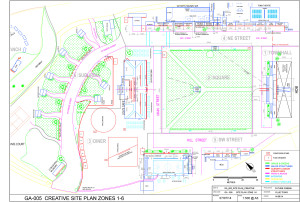

It is Secret Cinema presents… Back to the Future (BttF) which is the focus of the analysis of this article. Announced in June 2014, the event sold out 42,000 tickets in the first four hours, and then went on to sell almost 80,000 for the experience which ran throughout the summer of 2014. The cinematic spaces of the world of BttF were actualized as a ludic landscape, in both online and real-world spaces. In what follows, we look at some of the key qualities of this multi-faceted experience to interrogate the extent to which the aesthetics of games and play form can facilitate greater understandings. If this is ludic cinema – what kind of ludos is present here? We will explore the playfulness of the SC aesthetic experience by drawing parallels to the originating BttF cinematic text(s) and their concomitant audience pleasures, interactions and manipulations, whilst also interrogating audience behaviours and affect both during their preparations for, and at the SC event itself. We will draw on the critical vocabularies of the now established field of Game Studies to examine the extent to which the experience as designed assumes gaming or playful literacies on the part of the participant and borrows from or extends existing game aesthetics in the spatialisation and elaboration of the BttF world. In doing so, we will be drawing from influential approaches which draw attention to the aesthetic and affective dimensions of cultural experience as lived and embodied alongside significant critical work which has deployed early twentieth century play theory in the examination of contemporary games in terms of formal qualities but also in terms of player experience (Dovey & Kennedy 2006, Giddings 2008, Giddings and Kennedy 2009, Taylor 2006). In the following we identify some productive areas for close examination – the extent to which navigation and exploration are central features of the experience as both designed and embodied; the function of role-play as a structuring dynamic for participant engagement and also for designer control and rule formation; the evidence of a system of rewards for expert player/participant performance; the instances of collecting and accumulation as a central element of player engagement with the story as a pre-existing text and in terms of their experience as participants in the SC live event.

Online space – on becoming a resident of Hill Valley – from payers to players

As a participant or player, the BttF experience was shaped and tightly controlled from the moment of successful ticket purchase. Through online spaces and social media channels, participants were able access the fictional spaces of the experience via numerous ‘diegetic portals’ (Atkinson, 2014b), and invited to get into character. The fictional locale of BttF’s ‘Hill Valley’ was recreated in numerous in-fiction websites as well as in the physical spaces of ‘pop-up’ stores which opened up in East London in the weeks leading up to the main event in which visitors were greeted and served ‘in-character’ by Hill Valley residents. There was also the frequent publication of articles (online and in newspaper form) leading up to the Hill Valley fair (the proposed context of the live event), as well as a TV station (HV-TV) broadcasting via YouTube. These elaborations and embellishments of the fictional far exceeded previous events and were aimed at making the shows increasingly interactive and immersive, combining elements common to virtual worlds and pervasive games.

Within the ‘fictional’ social media strategy – ticket-holders were required to log in to the Hill Valley website using a secret access code that was embedded in an introductory email. Audience members were assigned new identities and issued with printable business cards which they were instructed to bring along to the event, which communicated their new name, address, telephone number and assignation to one of Hill Valley’s constituent organizations. Audience members were then given specific instructions of what to wear and what to bring to the event. For example, Hill Valley High School students were required to bring their homework and photographs (at the event students could then decorate their own locker in the school). Town Hall staff members were asked to bring banners, flags, posters and rosettes to support the Mayor Red Thomas re-election campaign (which were then used as props by participants taking part in a pre-screening parade).

Engaging in these activities enabled audience members to begin to immerse themselves into the diegetic fabric of the BttF filmic universe well in advance of attending the event. These interactions also worked on the level of introducing new characters to the audience, who don’t feature in the film, but contributed to an expanded diegetic canvas of the fabula of BttF. They also enabled audience members to contribute to the textual spaces of the experience and provide new content for sharing. For example, on the Hill Valley Telegraph staff page – members were asked to write articles on recent (imagined) news, these were then included on the dedicated website. One of our respondents was clearly delighted to have his pre-event engagement rewarded in this way:

Before the event I wrote a letter to the Hill Valley Telegraph about moving here from New York, which was ‘printed’ online (11b).

Audience members were also provided with instructions on the most appropriate clothing to wear through a downloadable Hill Valley ‘Look Book’. Alongside the issuing of a new identity and the very specific instructions regarding how to engage with the event, these instances could collectively be considered as the ‘rule set’ for BttF as a role playing environment, as we shall now explore below. It is also clear from these pre-experience responses that the participants took pleasure in the elements of role play and performance that were afforded:

I’ve realised you have to put something in to get the best experience. I have a 50s outfits already, I’ve visited the stores and I think I will pretend to be a character when I’m there (10a).

I plan to enjoy the surroundings and interaction with other fans and engage in character roleplaying to enjoy the moment (3a).

These preparations enabled audience members to occupy the physical space of the narrative diegesis of the Hill Valley fair prior to the screening in what we refer to as an intra-diegetic play-space in which participants take on a role through their embodiment of in-world characters to navigate and explore, and immerse themselves in the extensive fabula initially established online.

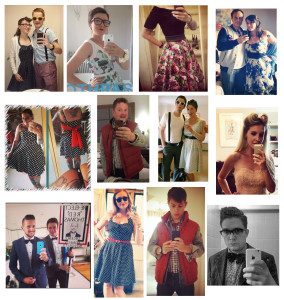

Players/participants celebrated and shared their preparatory engagements in a series of behaviours which share much in common with Cosplay (see Figure 2). Cosplay is a practice that aligns closely to film-fans, cinephiles, cartoon devotees and gamers (Gn 2011, Lamerichs 2011). In this instance, it was initially very closely policed by organizers and other fans, and in audience-generated tip-sheets – ‘to get the best experience’ (48a).

Despite the presence of a rule-set as described above, since so many of the BttF participants are established devotees and fans of the text, they arrived in their own self-selected identities – many of them choosing to play key central characters from not just the first BttF but also the two sequels. These minor acts of disobedience led to a preponderance of Martys, Biffs, Goldies and Docs whose actions and behaviours were easily confused with those of the actual professional actors who shared the landscape. Said one participant:

I always dress as Doc Brown to fancy dress parties and am a bit of an inventor like him! (7b).

This mirrors the on-screen BttF character engagement in constant ‘cosplay’ throughout the trilogy as key characters don decade-specific disguises. This confusion of the participants performative identity through the juxtaposition of conflicting temporal referents created a verisimilitudinal dissonance within the event.

The eclectic result of audience ‘cosplay’, captured by the mode and aesthetic of the social media selfie

The eclectic result of audience ‘cosplay’, captured by the mode and aesthetic of the social media selfie

These decorative cosplay activities closely resemble pervasive game behaviours and most specifically the Live Action Role Playing (LARPing) format. The participants consistently described the necessity to be ‘in character’ in order to benefit fully from the experience combined with a consistent recourse to terminology of ‘liveness’ in order to describe the event:

LIVE, immersive, entertaining, exhilarating, escapist, awesome! (17b).

I hadn’t been to the cinema nor had I been to the theatre, it was one massive blend of both that worked so well that it felt like I was actually in the film” (7b emphasis added)

The instantiation and mode of participation was directly similar – characters were ascribed and developed in advance, costumes were adopted and participants were invited to engage with the location, the inhabitants and other ‘players’ as their adopted persona.

Real-world spaces

Upon entering the SC site, participants enter the spatialization of the film’s fabula through the actualization of the fictional locale of BttF, in which the chronological ordering of the filmic time and syuzhet (plot) is recreated through the carefully simulated topology of Hill Valley (see figure 2). The approach to the site is marked with a ‘2 miles to Hill Valley’ sign, which leads the audience through Otis Peabody’s farm – Marty’s first arrival point in 1955. As with a theme park the route around the territory was heavily proscribed but difficult to absolutely control and was subject to meanderings and wanderings. The participants play their own part within this highly crafted mise-en-scène, as residents of Hill Valley navigating the difference spaces and encountering the different characters in order to accumulate knowledge, experience, and souvenir items. Close to the entrance, and right at the start of the experience participants can be photographed by the iconic and familiar sign for the yet-to-be-built Lyon Estates. Just as Marty McFly is a time travelling visitor to these spaces in the film, participants are at times positioned as tourists/flaneurs and later are able to purchase a disposable camera through which to record their journey and the spectacle. The navigable space dissolves into the Hill Valley town square – a miasma of styles, aesthetics, sounds and sensations.

The site includes recreations the family homes of the film’s key characters, Lou’s café, the High School, and a plethora of shop fronts. The fabric and iconography of SC’s recreation of Hill Valley is notably drawn from the entire BttF trilogy. This provides a deeper and more expanded frame of reference from which SC has drawn both textual and expositional detail.

Hill Valley’s recreation translates into a ‘film-set’ aesthetic in which all buildings appear as facades fabricated through theatrical flats and materials, and illuminated by stage lighting. The sense of the simulacra of the film set, as opposed to that of a real-world location is further compounded by the context of the Olympic park site which is overshadowed by the highly visible commercialized environment of the present-day consumer Westfield mall and by the UK’s tallest sculpture ArcelorMittal Orbit which looms large over the 1955 landscape. This sculpture is playfully referred to as ‘Doc’s Rocket Propulsion Device’ on the accompanying map of the site.

This confliction of multiple synchronous temporal-visual-referents is further complexified by the audience member’s eclectic/anachronistic dress-styles (as described above). The visual disorientation and temporal incoherence continues throughout the navigation of the various instances of 1950s pastiche and an undeclared corridor through which you can stumble in to a 1980s bar. The confusion of styles across three disparate decades is symbolized by the ubiquitous presence of anaglyph 3D glasses (which can be purchased for £1 in the 80s bar). These have no practical application on-site, instead they are the reproduction of a prop worn by a character in the film. But they can also be seen to act as a coherence device to link the 1950s, 1980s and 2010s – the three key eras in which 3D-cinema technology has been popularised. Moreover, the wearing of the glasses can be seen to symbolize the knowing mediation of the spectacle that the participants are witnessing, an acknowledgement that these are screen-mediated events, both created and experienced through the prism of the grammar and aesthetics of cinema. The absurd redundancy and silliness of wearing the glasses whilst wandering through the Hill Valley environment also signals a ‘lusory’ attitude to experience and indicates an affect of being at play (Dovey & Kennedy 2006, Raessens 2014). This is reflected in one participant responses who described the sensation as:

a three-dimensional entertainment experience. You’re in the film for the length of the film (1c).

This cacophony of styles and time referents unintentionally mirrors the intrinsic postmodern textual aesthetics of the BttF films, in which scenes contain simultaneous mixed time-period metaphors, cross-pollinating through costume, props, dialogue and mise-en-scène. Time itself is a matter for textual and narrative play, for example, in 1885 in BttF 3 – Marty is seen doing a 1980’s moonwalk as the character Mad Dog Tannen fires bullets at his feet. In the same film, we see a modified Delorean which is a hybrid of both 1950s and 1980s automobile features. Just as alternate futures were envisioned in the films of the BttF trilogy (for example, an alternate 2015 and a dystopic 1985) so to are the alternate histories of 1955 recreated in the spaces and costumes of SC’s rendering. The experience presents and perpetuates a version of the 1950s that never existed in actuality through the materiality and digital materiality of the present day.

Roleplay Aesthetics

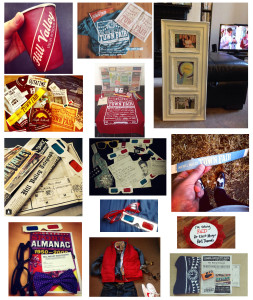

The experience includes a number of (interactive) narrative vignettes in which audience members are invited to engage with the fictional characters and with one another in activities and games that relate to a specific context. These included competing in the ‘Six at Six’ radio competition, participating in a signing lesson at the school, and joining in at a neighbourhood-watch meeting. The street performers contributed to the gamelike experience by providing the mechanism through which further activity and reward could be garnered. These performers would engage or be engaged by the player, at which point they would reveal the fundamental elements of their character and, if the correct series of verbal responses were given, they were able to assign the player a quest, or, in some cases, a simpler immersive experience such as answering questions on a game-show or being told a story. These mini-quests were occasionally rewarded with souvenirs (see figure 3) or participation in the Hill Valley Parade. As one respondent stated:

…we both got enrolled in the apprenticeship program and had to carry out a few tasks to complete this, unknown to us we had drawn a huge crowd and everyone was cheering us on! amazing. The Texaco guys invited us to take part in the Hill Valley parade before the film, well that was it for me, kid in a candy store! We joined the parade and had to wear Texaco boiler suits and carry a tyre along the route singing the Texaco song! This was a moment, as a massive BttF fan, that I will always remember (7b).

This will be familiar as a structure for creating multiple narratives within one setting to any player who has previously taken part in video-RPG sandbox games or even board-game or live-action variations not based on film text or setting. A notable similarity is the availability of the option for the player to ignore all the quests and even the exploration potential and do something arbitrary or ‘normal’ in the spaces of the map which weren’t reserved for the quest such as sit in a bar and drink. If the player chose this option at the BttF event, instantly the experience would lose most of its ‘game’ elements and simply become more similar to a themed festival or a costume party. In this same vein, fairground rides featured, demonstrating the curious mixture of immersive action and non-specific revelry, or to deploy the Caillois system of categorisation of play – mimicry (playing a role) and ilinx (the thrills of the fair ground).

Along with navigation, acquisition is a key part of many game modes, especially RPGs, whether you’re collecting coins, bottle-caps or medi-kits, and within the Hill Valley site there were a lot of mechanisms through which this could be achieved, not only by way of the quests as mentioned above. A dress shop which sold fifty-dollar dresses and a record shop selling five dollar albums were key indicators of the organisers’ desire to use the experience not only to sell tickets but to sell merchandise (see Figure 3).

Audience/player generated content accumulated both in the lead-up to the event and during the experience

The BttF experience facilitated two ‘play’ modes which would be familiar to gameplayers; story or sandbox. In story mode gameplay is determined by successful completion of a sequence of events, action or interactions often thinly aligned with an overarching narrative. In sandbox mode players are allowed to interact within the gameworld, complete smaller non-sequential and open-ended tasks. For BttF adept or expert story mode players who knew the precise geographies and temporalities could explore the environment more purposefully and would be rewarded for their successful navigation by being present as the live-enactments took place also allowing them occasionally to play minor roles in this action.

As we loved the film and knew the plot well we had a good idea of where things would be happening when, for example we waited on the residential street for the scene where Marty gets hit by his grandad’s car (9b).

Collecting a complete set of these story driven interactive “cut-scenes” is a clear reward for expert engagement with the story mode. These cut scenes, akin to the non-interactive live action sequences of a computer game took the form of reenactments in locations across the site by key characters in the same chronological ordering of the film’s syuzhet. These span Marty’s arrival in Hill Valley, his encounters with the 1955 version of his parents, and his meeting with Doc. These are uncanny in their emulation – played by actors who resemble their on-screen counterparts in costume, but in features and build – are clearly different. These moments are pre-empted by the growing crowd surrounding the action and through the sudden arrival of ‘out-of-character’ stunt crew surreptitiously whispering into communications devices in order to cue the live action vehicles and to keep audience members away from their approach. These moments reveal the representational practices of filmmaking ‘Style’ (Bordwell, 1997) and signal an emerging semiotics of the artifice of film production which is ever-present throughout and arguably characterizes the entire SC experience, a case of the ‘text making strange its own devices’ (Polan, 1985, p. 662).

Once the screening has commenced the participants are no longer individuals but become part of a community of viewers who engage together in prompted and unprompted behaviours and aesthetic responses. Some of this participant behavior is carefully crafted – just before the screening commences the crowd participates in a ‘dance along’ which is a fitting prelude to the stillness required for group viewing on a single tier simulated lawn. During this aspect of the experience the players are subject to a “recombinatory aesthesis” as they are surrounded (literally enclosed within) screen and live action re-enactments allowing for an “amplification of affect and effect [as players respond to and experience] visual and kinaesthetic pleasure” (Giddings & Kennedy 2008, p. 31).

The viewing experience of the film is augmented by a number of synchronous off-screen reenactments of on-screen action which include the opening sequence of Marty’s trip to school set against the Power of Love soundtrack in which he is towed by a vehicle on his skateboard around the 1985 Hill Valley square; the reveal of a replica smoking time-travelling Delorean; the dramatic chase by the Libyan terrorists and Marty’s arrival in the 1955 town square of Hill Valley. Stunt doubles are used for the main characters in the action scenes – although their costumes are identical, their physical appearances are clearly different – which once again reveals the representational practices of filmmaking style and artifice through the inevitable presence of continuity errors.

As well as these highly choreographed moments of meticulously matched action, actors simultaneously perform key dialogue sequences which include George’s confrontation with Biff at the dance and his subsequent romantic union with Lorraine. These moments which are carefully lip synced (although are invariably ‘out-of-sync’) by the off-screen versions of the characters again invoke a sense of the uncanny, of the familiar made strange. Moreover, these moments of mismatched stunt doubles and out-of-sync dialogue reveal further representational aesthetics of film production. The filmic text(s) of the BttF trilogy also contain such moments during the repeated action, for example, the reenactment of the 1955 scenes in BttF 2 include older (and sometimes different) versions of the actors. This acceptance by the cinema (and SC) audience of the mediation of filmmaking process has become the source of some cinematic fan practices (i.e. spotting continuity errors).

Hill Valley Sandbox & Emergent Play

At one particular moment an unintentional continuity error occurs, which signals a shift towards the experiences becoming a self-referential and playful text. This occurs in the off-screen simultaneous action in which the two versions of Doc are in-sight of the audience – the stunt version of Doc is still visibly uncoupling from his dramatic descent on the zip wire, whilst the actor-version of the Doc appears on the ground to deliver the next scene. This off-screen (SC) continuity error uncannily occurs at the same scene in the BttF 2 film’s syuzhet in which two versions of the Doc are also (albeit deliberately) visible on screen – the original 1955 Doc is seen setting up the electric rig to the clock from the point-of-view of the 1985 Doc. This unintentionally reflexive, meta-fictional (Waugh 1984, Holland 2007) moment mirrors the postmodern aesthetic of self-reference characteristic of the three BttF films. For example in BttF 3 Marty makes a comment about lack of time, ‘ten minutes, why do we have to cut these things so damn close’ highlighting the characters’ awareness of the film’s creation and the dominant running-out-of-time aesthetic. In another instance, Marty and Doc swap their character’s catch-phrases (‘Great Scott!’ and ‘This is heavy’). In SC, this action of dialogue quotation and re-quotation is an act in which audience members delight, for example, in numerous respondents telling us that they approached the character of Goldie Wilson telling him that he should run for mayor. The audience’s pleasure in the repetition of character lines and catch phrases is a playful participatory practice evidenced in other instances of (cult) cinematic reception (such as the The Rocky Horror Picture Show, see Austin, 1981).

Like other forms of live play events and despite the presence of rather precise rules and a tightly controlled environment, the BttF experience produced moments of emergent gameplay. As one participant commented:

It was a completely personal experience that would be unique to each person, depending on how you chose to spend your time and what you happen to stumble across as you explore the world they created (8b).

Emergent play is more open ended and less dependent upon the overarching narrative and more upon elements of chance and the extent to which the participant was willing to engage with others around them. “These occurrences often lead to intensive and fun game experiences, which have not been planned by any designer or participant” (Montola, Stenros & Waern 2009, p. 18).

On arrival at Hill Valley, there was also a school bus recruiting passengers who could travel directly to a point much later in the ‘story’. In this sandbox mode the participants could visit the fair, dance to 80s music, drink cocktails, play videogames & buy 80s themed merchandise, gorge themselves on burgers, fries and milkshakes at Lou’s café and then drink more themed cocktails at the 1950s Enchantment Under the Sea high school dance in the style of the disjunctive, discontinuous, vertiginous and unruly carnivalesque. The story does not entirely drop away of course – SC’s Hill Valley is populated by ‘characters’ from the world of the film delighting the audience with small recurrent set-pieces throughout the environment. The headmaster of the high school, Strickland, is seen issuing detentions, George McFly cycles around the square engaging the audience in conversation, while Police officers reprimand audience members for jay walking. As one participant commented:

I took part in Doc Brown’s experiment (which was hilarious) and got picked on by bullies twice, which was weirdly the highlight for me (3b).

This open mode and the recurrent nature of these behaviours allows for multiple points of view which is also a defining aesthetic feature of the BttF films – whereby similar sequences are repeatedly replayed throughout the trilogy.

Like other forms of game (console, online, pervasive etc.) SC’s BttF can be understood as an event that has been designed, constructed to expect or require specific behaviours, attitudes and literacies on the part of the participants. It is only through these that the event comes into being – key to participation is a willing adoption of this ‘lusory attitude’ – the willingness to engage in the act of playing ‘as if’ (Suits, 1990). In this context, playing ‘as if’ in the world of 1955 as constructed through these film texts. The extent to which the player or participant is willing to ‘give themselves up’ to the required behaviours; to play out a role consistent with the world as designed is seen by our respondents as key to pleasurable and successful experience. As one respondent articulated:

It is immersive. You play a part in it and have a great time interacting with other actors and ticket holders. The more you put in the more you get out (2b).

This description of appropriate affective engagement indicates the extent to which player effort is rewarded by greater levels of immersion and experience of presence.

Conclusion

SC’s BttF is an interstitial experience, one that occupies a liminal space between theatre, game and a filmic text; the simulacra of its making and the playfulness of its reception. It is navigated and ‘played’ by a highly literate audience attune to interactive engagement with cinematic texts through a variety of fan practices and familiarity with video game-play. The event enabled the formation of a playful and ‘dramatic community’ (Atkinson, 2014a) in which the impact of game cultures and a ludic aesthetic upon cinematic audience spectatorship could be clearly identified. This SC project marks a new point of departure in the evolution of what has been described as the ludification of culture and cultural experience (Raessens 2014).

Our theoretical integration both challenges and begins to extend the textual analysis approach of film studies, through an expanded consideration of the permeation and manipulation of the filmic text beyond the screen and by the audience. By recourse to game studies approaches we have been able to tease out the ways in which the designed elements and player responses can be understood in relation to the mechanics of games and play forms.

Bringing together the critical vocabularies of play theory and film theory within this paper begins to afford some purchase on the complexity of this experience. However, this phenomena marks out new territory and an evolution of a new form of cultural experience worthy of its own critical vocabulary sufficiently nuanced to capture its aesthetic and affective complexity which we hope to have initiated. As games become increasingly cinematic and event cinema becomes more gamelike and playful a new integrative theoretical and conceptual model will emerge.

– All images belong to their rightful owner. Academic intentions only. –

References

Atkinson, S. (2014a). Transmedia Critical | The Performative Functions of Dramatic Communities: Conceptualizing Audience Engagements in Transmedia Fiction. In International Journal of Communication, 8 (pp. 2201–2219).

Atkinson, S. (2014b). Beyond the screen: Emerging cinema and engaging audiences. New York, NY: Bloomsbury.

Austin, B.A. (1981). Portrait of a Cult Film Audience: The Rocky Horror Picture Show In Journal of Communication 31–2.

Bordwell, D. (1997). On the History of Film Style. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

De Mul, J. (2005). The Game of Life: Narrative and Ludic Identity Formation in Computer Games. In J. Raessens, J. Goldstein, (Eds.), Handbook of Computer Game Studies, 251–66. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Dovey, J., Kennedy, H. W (2006). Game cultures: Computer games as new media, Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

Giddings, S., Kennedy, H. W. (2008). Little jesuses and fuck-off robots: on aesthetics, cybernetics, and not being very good at Lego Star Wars. In: Swalwell, M. and Wilson, J., (Eds.), The Pleasures of Computer Gaming: Essays on Cultural History, Theory and Aesthetics. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, pp. 13-32

Giddings, S. (2009). Events and collusions: A glossary for the microethnography

of videogame play. Games and Culture: A Journal of Interactive Media , 4 (2). pp. 144-157.

Gn, J. (2011). Queer simulation: The practice, performance and pleasure of cosplay. In

Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies, Vol. 25, No. 4, August, 583–593.

Holland, N. H. (2007). The Neuroscience of Metafilm. Projections, 1, 59-74.

Hall, S. (2000). Who Needs ‘Identity’? In Paul Du Gay, Jessica Evans, Peter Redman, (Ed.), Identity: A Reader, 15–30. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Jenkins, H. (2004/07/10). Game Design as Narrative Architecture. Retrieved from http://www.electronicbookreview.com/thread/firstperson/

Lamerichs, N. (2011). Stranger than Fiction: Fan Identity in Cosplay. In Transformative Works and Cultures, no. 7.

Retrieved from http://journal.transformativeworks.com/index.php/twc/article/view/246/230

Montola, M., Stenros, J., Waern, A., (Eds). (2009). Pervasive Games Theory and Design: Experiences on the Boundary between Life and Play. Burlington: Morgan Kaufmann.

Polan, D. (1985). A Brechtian Cinema? Towards a Politics of Self-Reflexive Film. In Bill Nichols (Ed.), Movies and Methods: An Anthology. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Raessens, J. (2014). The Ludification of Culture. In Fuchs, M., Fizek, S., Ruffino, P., Schrape, N. (Eds.), Rethinking Gamification (91-114). Leuphana: Meson Press.

Suits, B. (2005/1978). The Grasshopper: Games. Life & Utopia New York: Broadview.

Taylor, T. L. (2006). Play between Worlds: Exploring Online Game Culture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Tolstad, I.M. (2006). “Hey Hipster! You Are a Hipster!”. Oslo, Norway: The University of Oslo.

Waugh, P. (1984). Metafiction: The Theory and Practice of Self-Conscious Fiction. London: Routledge.

Author contacts

Sarah Atkinson – s.a.atkinson@brighton.ac.uk

Helen Kennedy – h.kennedy@brighton.ac.uk

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.