Abstract

Our overly fearful risk society has eliminated much of the beneficial risk that should exist in contemporary games. Games that incorporate actual risk by design can help us overcome delimiting and harmful fears, habits, and laws. Riskier games expose our self-imposed limitations, creating opportunities for us to grow past them. Bust A Cup is a risky game that serves as exemplar in this paper but other games such as Brutally Unfair Tactics Totally Okay Now, Pac-Manhattan, and BorderXing Guide will also provide perspective. These games are risky by design, empowering players to engage in varying degrees of danger that may be legal, physical, and in some cases merely perceived. They reward recklessness with gameplay advantages and are as safe as players collectively decide to make them.

Keywords

Play, risk, risky games, game design, physical games, broken games, risk society

Introduction

This paper looks at some of the negative effects from how we conceptualize and mitigate risk in society. Then it examines how games that afford varying degrees and types of risk can help counteract those negative effects. Risky games offer opportunities for players to face, feel, and redefine self-imposed limitations that protect us from danger or injury. The primary game examined is Bust A Cup, although other risky games are studied to provide perspective and contrast. The paper will also advise how to afford risk by design while avoiding the popular, unfortunate aesthetic of human destruction. The paper closes with the argument that risky games can serve a vital function to society by embracing a form of political protest akin to certain forces within the historical avant-garde.

Risk Society

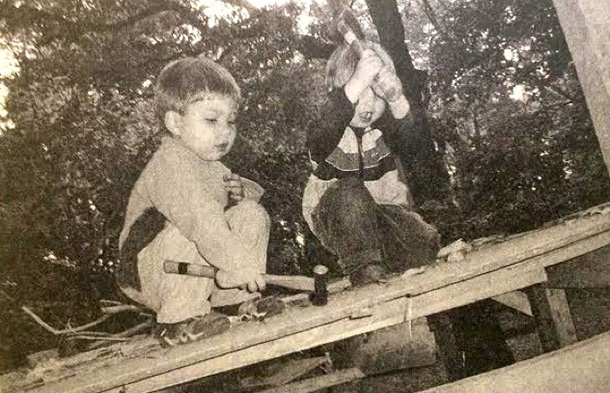

Figure 1 Children wield hammers in the chaotic, messy play space of Hanegi Playpark in Japan. Image from Savage Park: A Meditation on Play, Space, and Risk for Americans Who Are Nervous, Distracted, and Afraid to Die (Fusselman, 2015, p. 34).

Risk is the exposure to danger, injury, or loss. Amy Fusselman (2015) explores how we have stripped childhood of risk-taking without actually making it any safer in Savage Park: A Meditation on Play, Space, and Risk for Americans Who Are Nervous, Distracted, and Afraid to Die. Fusselman promotes “adventure playgrounds”, curated junkyards for kids who are only minimally supervised. Adventure playgrounds are stocked with building tools such as saws, hammers, box cutters, nails, rope, and assorted trash such as rusting boats, mounds of old tires, and deteriorating piles of wood, enabling children to navigate risk of minor injury according to their own emergent play interests such as constructing whimsical or ramshackle play structures. Adventure playgrounds are not popular in the United States due to their perceived risk and exposure to litigation.

Adults have become increasingly averse to their own risk as well over the past few decades. Mainstream news media have become more alarmist, contributing to an overwhelming sense that we suffer from a growing litany of calamitous risks from terror attacks, to new infectious diseases, climate change, and so on. German sociologist Ulrich Beck coined the term “risk society” to define how society organizes in response to risk. Our risks are no longer limited to regions, territories, or countries. They have become spatially unbounded, each with myriad contributing factors—many unknown or uncharted. Agencies charged with risk management seem decreasingly able to assess and mitigate short and long-term dangers. According to Beck “the hidden critical issue in world risk society is how to feign control over the uncontrollable—in politics, law, science, technology, economy, and everyday life” (Raley, 2009, p. 35). We realize that we cannot effectively control our growing systemic risks so the best we can do is pretend to minimize them, for example with security theater in U.S. airports. The more we minimize risk the more we close off ways of being, thinking, and socializing that are integral to questioning and adapting our place and purpose in the world.

The Counterintuitive Result of Getting Beaten Up

As a writer, educator, and designer I strive to diversify why and how games are made as well as what games can do and mean. One of the ways I help realize these goals is by allowing game design practice to inform life experience and vice versa. My games are inspired by things that happen in my everyday life, and, conversely, I try to allow a ludic mindset to inform aspects of my behavior and life choices. For example, I bring a playful open-mindedness to where I choose to visit in Chicago or while traveling in Cambodia, Mexico, Colombia, the Philippines, etc., and whom I choose to interact with. This brings me into neighborhoods and into contact with people whom my social circle or better judgment may deem dangerous, uninteresting, and so on.

The impetus for developing the game Bust A Cup and ultimately this paper was getting beaten up. In the fall of 2014, I suffered an unprovoked attack by three strangers on the street in Chicago. I was not given a chance to give up my property before the attack, which happened suddenly out of nowhere. It is unclear if the assailants wanted to rob, assault me, or both. Without warning, an assailant choked me while another beat my head and ribs with a socket wrench and a third punched my stomach. The attackers pinned me to the ground as they beat me but I did not pass out or give up. I got up several times as they kept beating me down. They kept screaming, “Stay down!” but I did not. Although I did not fight back effectively, I was able to work my way free eventually due to adrenaline, terror, and resolve.

The event was traumatic leaving me injured and shocked. However unfortunate, it taught me that my body is much tougher than I thought and my mind resolute when suffering a beating. Before the event, I did not know how I would react to an assault but now I do. My self-image changed after the beating, counter-intuitively causing me to feel stronger and more resilient once I worked through the initial shock and returned from the hospital. After I recovered from the trauma, I wanted to bring positive aspects of that experience to a game I would develop so players could realize their own resolve and resilience in the face of fear of injury. I wanted to let people play an artfully softened attack, as well as interpret and perform it each in their own way.

Bust A Cup

Bust A Cup (2014) is a physical two-player puppet brawler developed by the author and Brian Gabor Jr.

Coffee cups are placed upside down on top of “attack puppets”, crude wooden crosses armed with hammers, chains, and locks. The player who breaks her opponent’s cup wins. Maneuvering around in combat a player’s coffee cup wobbles and tinkles against the wood. As cups are not glued or attached to the cross in any way, but simply placed upside down on the vertical beam, if a player moves too fast or wields their attack puppet at an unusual angle the cup will fall off, break on the ground and that player will lose. This design prevents players from moving too recklessly. A foot-and-a-half metal chain is attached to the right end of the crossbeam. At the end of the dangling chain swings a metal Master Lock. The chain and lock serve as a range or distance weapon. On the left end of the crossbeam, a hammer hangs attached by a swivel that rotates completely around. The hammer serves as a melee or close-range weapon. Dexterous players can get the hammer propelling around by gyrating their cross in a circular pattern to build momentum. Staring at your opponent’s hammer whirling around during an orchestrated lunge is as mesmerizing as it is intimidating.

Figure 2 Close up of one of the attack puppets of Bust A Cup showing the chain and lock on the right, hammer on the left, and upside ceramic coffee cup on top. Image courtesy of the author.

Bust A Cup enables players to put themselves at varying degrees of actual risk that has been lost in contemporary games. It is a DIY throwback to the traditional duel, in which opponents settle disputes in a serious game of combat using swords or pistols. In Bust A Cup, swinging chains and spinning hammers whiz by tottering cups that shatter at your feet. New players grapple with learning how fast they can move without losing their cup. How aggressive are they supposed to play? How do they control this flailing puppet? What kind of attacks and parries can you invent with it? How silly or threatening do they look? The effect of playing Bust A Cup is a sense of lively embodiment navigating a clunky, cracked open experience.

Bust A Cup exerts a sociopolitical force through its spectacle of play. Ceramic cups smash on the asphalt when we play it in the alley outside DePaul University in downtown Chicago. The debris piles up crunching beneath the players’ feet. Players occasionally get nervous about the accumulating debris, noise, and attention passers-by give during gameplay. Bust A Cup reclaims public space for ostensibly reckless, performative play. It interrupts the lunch routine of passers-by who must reconcile the odd scene with the usual midday sidewalk flow. It is not a street brawl, but not quite the usual, safe urban game either. It is a LARP of a brawl. However, instead of roleplaying dramatic places, events, and people fantastic or historic, this is a LARP of a simple brutal act of street violence, a personal reinterpretation of a personal event. This is evident when discussing the game with players. Some have described it as the closest they have ever gotten to getting in a street fight, albeit a much safer, purely voluntary (and therefore less scary) street fight. It is a way to play through a scenario they fear and avoid, rendering it less foreign and enigmatic.

Audiences, players, and the game community must address new kinds of challenges when they are faced with novel, physically risky games such as Bust A Cup. Nobody knows how to effectively use the equipment and it is unclear how dangerous the game really is for players or even onlookers as cups and debris fly surprisingly far. For example, the organizers of Itty Bitty Bash, an indie game festival held February 25th 2015 in Chicago, wanted Bust A Cup to be played at the event. However, the game was ultimately rejected due to fear of litigation. Hopefully, risky games that afford underrepresented, psychophysically beneficial experiences such as Bust A Cup will be included in more festivals in the future in spite of such fears.

Design Goals of Bust A Cup

I created the game Bust A Cup with two development goals in mind. The first design goal was to create an experience that gives players an opportunity to experiment a loss of their usual sense of safety. I wanted it to feel a somewhat reckless and intimidating. It is supposed to foster an unstable frame of mind with regard to personal safety and aggressive performance. Liminal experiences such as this are rare in our usual flow of managed and mediated experiences crafted by mainstream designers complicit with contemporary risk society. In this way, Bust A Cup reclaims a sense of risk that our fearful contemporary culture wishes to close off from experience.

The second design goal of Bust A Cup is to deliver a more refined version of what I psychophysically experienced in my Chicago beating. That unfortunate, random attack taught me that I was hardier than I had thought. I wanted players to gain a sense that they could handle the threat of minor physical injury with playful enthusiasm, testing and impressing themselves—not to be self-destructive but the contrary—to be life-affirming beyond restrictive notions of the self, e.g. that they are not tough enough. Just as adventure playgrounds provide opportunities for children to actualize themselves through their chosen levels of risky play, Bust A Cup provides an analogous opportunity for adults. Combatants continually negotiate through body language and banter how aggressively to play. Some matches are borderline polite, as players gingerly feel out the game mechanics and chuckle at the spectacle, while other matches spring into action wildly with cups shattering into brick walls.

Broken Games

When we play Bust A Cup outside DePaul University in downtown Chicago, the spirit of gameplay is festive. The subversive charm of LARP brawls in an alley is liberating and joyful. At the same time, students tend to show concern, picking up the debris to minimize potential trouble. Players swing hammers and chains with care not to hit each other’s bodies, although occasional glances are inevitable. People tend to play in a civil, friendly manner due to the social context and setting.

When we hosted a Bust A Cup tournament outside a bar in Joliet, Illinois the mood was quite different. The crowd was more diverse and less familiar with each other. Inebriation led players to perform belligerently, sluggishly, or comically. Players accepted more risk in potentially hurting opponents as well as themselves. People did not care about the accumulating debris or trouble the ruckus could cause.

Doug Wilson noticed a similar divergent trend in player behavior with his 2011 game developed by the Copenhagen Game Collective, Brutally Unfair Tactics Totally Okay Now (B.U.T.T.O.N). People played more or less aggressively depending on the venue and social context. B.U.T.T.O.N is an unconventional party game for 2-8 players. To begin each round all the players set their controllers down near the screen and take a few steps back. When instructed, players race to grab their controllers and press a button while preventing opponents from doing the same. Different instructions around this theme add variety to gameplay.

Wilson (2011) argues that “that intentionally ‘broken’ or otherwise incomplete game systems can help nurture a distinctly self-motivated and collaborative form of play” because players have an unusual amount of agency to decide how brutal or sweet they may be. Depending on the overall mood, levels of inebriation, and familiarity, a player may decide to tackle opponents, turn off the screen, dangerously leap over people to win, and so on. Wilson reports that when drunk strangers played B.U.T.T.O.N. against one of the quiet, lanky developers, he experienced uncomfortable levels of hostility. Wilson analyzes the potential of “broken” games like B.U.T.T.O.N.:

In the company of friends or like-minded strangers, the punk rock, design-it-yourself spirit of the game can be liberating. But played carelessly – however we even define that – the game can quickly turn sour. Such are the opportunities and pitfalls of so physical and open-ended a game system, so obviously contingent on the particular players and the particular setting. Yet it is precisely because the game can go so wrong that it is so rewarding when the players manage to keep it going “right”. Its contingent nature might well be the main attraction. (Wilson, 2011)

Wilson proposes a design strategy for “broken” games:

My argument is that intentionally “broken” or otherwise incomplete game systems can help support a distinctly self-motivated and collaborative form of play. From a design perspective, the key to making these kinds of broken games work is to frame them in the right way. In this view, the practice of game design becomes less about crafting systems, and more about mood setting and instilling into the players the appropriate “spirit” (Wilson, 2011).

Whereas Wilson defines broken games as “working” when the spirit remains festive, positive, and fun, I propose that broken games can also work, albeit in a different way, when things break further, become unfair, or go awry. For example, during the Bust A Cup tournament outside the Joliet bar, a tall, hulking player dominated the latter half of the evening. He would invariably and almost immediately break any challenger’s cup. It was a sight to behold. His emergent strategy was to lunge forward and directly smash his cup against his opponent’s cup, often shattering spectacularly. I had never seen this strategy before. At the end of the night I discovered I had accidentally bought a stoneware cup that was harder than the ceramic cups I had purchased for the tournament at a secondhand shop earlier that day. Toeing up against an undefeatable champion was scary because of his precise, swift, violent attacks. Knowing he will win not only brutally but instantly made it much worse. The second time I challenged him he fiercely smashed his cup against mine in the initial moment of gameplay just as he had the first time. My cup’s debris sprayed across my face, grazing my chin and hand drawing blood. The superficial cuts contributed to the debauch vibe of the bar scene. A few reticent volunteers chose to challenge the champion only at that point, riding the frothing energy of a drunken crowd. Everyone cheered whoever would face such a formidable threat.

This “broken” event with an insurmountable champion was illuminating and valuable because it allowed players to face certain risk in play. It allowed people to face and process justifiable fear in a productive way. Psychologist and proponent of play Stuart Brown (2010) argues that play prepares us to better deal with risk. Brown’s oft-cited example is a scientific study involving two sets of rats. One set was allowed to play when they were juveniles while another set was not allowed to play. Later in their lives, both sets of rats were exposed to cat urine. The rats not allowed play as juveniles would not come out of hiding and died while the rats that were allowed to play as juveniles eventually came out and survived. Through play they had learned to be resilient to perceived threats. Similarly, during that particular evening of Bust A Cup people could face intimidating and certain defeat in an open and playful way. Even if only briefly, players had a chance to confront an unfairly matched Goliath aggressor, a sort of pseudo-bully—which was as empowering as it was frightening. Due to the actual bit of danger tamed by the seductive power of play volunteers could readily tap into their own and their friends’ perceptions of themselves as brave or cowardly and proceed to challenge those perceptions.

Risky Play Can Restructure Our Subjective Reality

By being open to things going wrong, broken games allow players to unearth and examine nuances of risk perception that may have sat unchallenged and undisturbed for years in their psyche. Risky games allow us to confront and diffuse fears in ways that are liberating, provocative, and productive to personal development. Some of us in game studies have long misunderstood the power of play, especially with regard to disruption and risk. Dutch anthropologist and landmark theorist of play, Johan Huizinga saw play as subordinate to the power of the real world. He argued that the former is always at the mercy of the latter. Huizinga (1970, p. 11) claimed, “the spoil-sport shatters the play-world itself. He reveals the relativity and fragility of the play-world. He robs play of its illusion”. It is easy to see where Huizinga’s formulation is indeed true: if you are broke and worried about paying rent or, more immediately, if you have to go to the bathroom, you may not feel like playing cards just now. But, more importantly, for Huizinga play is weak because it is based in fantasy, in our minds; and the ordinary world is formidable because it is the real physical universe. Yes, play can operate in a subordinate nature to reality. In many cases, play may be limited by the things we accept and know to be real. However, play may also be transformative of reality as we perceive, project, and construct it.

Brian Sutton-Smith, another key theorist of play, sees play’s purpose as questioning our usual way of acting and being in the world. This is in opposition to Huizinga’s formulation, which sees play as subordinate to reality. For Sutton-Smith play’s purpose is to restructure reality. To be specific, play reinforces variability from rigid, successful adaptations. Play enables organisms to push past hard-won patterns that have become fixed having ensured past survival. The established way of doing things may work, but some new experimental way of doing things—although riskier because unproven—seems like it could work and might even be fun. Literary critic James S. Hans has picked up and extended this thread. Hans laments play in our risk society has become so safe and manageable that it has lost its vitality and purpose. Contemporary culture has done its best to minimize and manage risk in play rendering it frivolous and antithetical to its purpose. A player wholly engaged in play does not only place himself at risk; he places his world at risk by giving himself up to play’s dynamic and unpredictable flow. A fully realized player:

places everything at risk, and not in the naive sense that he must consider the consequences of his action on other people as well as himself… One risks the world precisely by giving oneself up to it… we have done our best to eliminate the risk in play, to make it ‘safe’ for society. We almost need to relearn from the beginning that play is always only play if something is really at stake, or if everything is at stake. (Hans, 1981, p. 182-183)

A value of play is that it allows players to question the patterns in which we think and interact in the world. Play can accomplish this by incorporating actual, variable kinds of risk, dissolving limitations that conform our actions in everyday life. It can publically challenge the conventional wisdom of risk society. Players of Bust A Cup can, for example, play their way to a stronger self-image. Playing it in urban environments can open up livelier physical actions in shared public spaces.

At any stage of our lives we may playfully open alternate ways to be and perform in an unstable world full of dangers and potential, although traditionally, the younger we are the more we perceive and play with reality in that way. In terms of childhood development, to willfully hallucinate with “an intermediate reality between phantasy and actuality is the purpose of play”, according to developmental psychologist Erik Erikson (2000, p. 104). The more often we can revisit that mindset of that developmental stage, the more we may face, feel, and transform ourselves and our world throughout our lives at any age. By embracing risker kinds of games, games that put into question chosen aspects of our identities and reality that the designers select, the more purpose play may have over our world and our lives. Designers of so-called “serious games” who wish to transform the world would do well to open their gameplay experiences to such risk in order to achieve the broader and more fundamental sociopolitical change that they aspire to foment.

Beyond the Aesthetics of Human Destruction

I would like to distinguish the kind of play I am advocating from the “aesthetics of human destruction” that cultural theorist Paul Virilio describes in his book Art and Fear. According to Virilio modern artists of the 20th century celebrated the destruction of humanity and the human world in their art, evidenced through grotesque deformations of the human body in abstract expressionism, the breakdown of human vision in cubism, and so on:

[I]t was through the carnage of the First and Second World Wars that modern art, from German Expressionism and Dada to Italian Futurism, French Surrealism and American Abstract Expressionism, had developed first a reaction to alienation and second a taste for anti-human cruelty. (Virilio, 2006, p. 2)

Via broken games, we should not advance cruelty or risk danger, arrest, or humiliation for a masochistic thrill at the prospect of destruction. Nor should we advance these games to revel in the injury and misfortunes of others. Like effective avant-garde art, games that offer risky play should not advance fear or shock for their own sake. The purpose of risky play is to affirm life and diminish alienation. It should help us face and feel ourselves and our world in new ways, not further separate us. It is to enrich our being, to cultivate a stronger sense of presence in the world as well as a greater plasticity of self. It is to diversify our experience beyond the happenstance of our personal histories; to feel more alive in rich connection with this mysterious, surprising, and continually unfolding world.

Jackass: The Movie (2002) can alter the viewer’s sense of how much, or more precisely how little, at risk the human body is of injury in motley, stupid reckless situations. The film is a series of comically idiotic, dangerous stunts performed by regular actors rather than professionally trained stuntmen. For example, in one scene Steve-O, donning only underwear stuffed with raw chicken, attempts to walk across a tightrope over a pool of alligators. In another scene, the performers crash golf carts through a miniature golf course. Yet another depicts Steve-O alternating back-and-forth between snorting wasabi and vomiting. The aesthetics of human destruction has been popularized and made visceral in YouTube communities, who celebrate backyard wrestling mishaps, testicular abuse, and a litany of horrors comprising a mosaic of human suffering that might delight Hieronymus Bosch. Most videos of injury or humiliation in this genre lack the context and continuity of the Jackass franchise. Jackass features reoccurring performers, such as Johnny Knoxville and Steve-O facing certain danger after danger. The most shocking aspect is how they never or barely get hurt. They demonstrate that after an endless stream of abuses the human body keeps going if armored with a sense of abandon and bottomless humor. Jackass Number Two (2006) was a Critic’s Pick with Nathan Lee describing it in The New York Times as:

[d]ebased, infantile and reckless in the extreme, this compendium of body bravado and malfunction makes for some of the most fearless, liberated and cathartic comedy in modern movies… At the root of the ‘Jackass’ project is an impulse to deny the superego and approach the universe… as an enormous, undifferentiated playpen. (Lee, 2006)

Lee articulates why Jackass is able to surpass the aesthetics of human destruction and achieve something greater. Steve-O and other performers consistently demonstrate a state of being that is open to actual risk. They show us how to play in a way that has been lost in much of contemporary risk society and how to break our overreliance on safe, overly managed activities. They remind us that we can loosen up and clutch into the shards of the unknown—we will probably not get too hurt—so we may manifest a more open, playful life.

Risky Games are Politically Avant-garde

Much of the popular critical discourse around videogames over the past few decades has been around safety and violence. Similarly, much of the popular critical discourse around sports in the United States has focused on injuries and safety. Beyond sports and games, other ludic media such as Jackass has been criticized as encouraging people to injure or kill themselves or others as they imitate or invent risky behavior inspired by the franchise.

These criticisms are justified and should weigh in debates on risk society sports, games, and entertainment. People who defend the right for Jackass, or violent videogames for that matter, to exist tend to do so on legal grounds such as our protections around free speech as well as with values of individual liberty and the pursuit of happiness. People who defend American football invoke cultural tradition, history of the sport, and the popular entertainment it provides. Both sides of these debates have valid points. I simply wish to add another point to consider.

Experiences that allow us to voluntarily engage in risky behavior enable us to face, feel, and transform ourselves as well as our world. They prepare us to accept more uncertainty in life and even playfully thrive in the face of justifiable fear. If left unmitigated, risk society is destructive on a global scale as it nationalizes, institutionalizes, and normalizes fear. The United States’ response to 9/11 with the War on Terror and TSA security theater were fueled in part by America’s inability to accept lingering perceptions of risk. The Obama Administration’s expansion of drone warfare to kill potential enemy combatants in their homes, sometimes along with the collateral damage and death of their friends and families, also stem from our inability to accept the risk of letting them live. If considering potential negative effects of risky games on society let us also remember the positive effects, such as helping to inoculate society against fear that can be fueled and manipulated to justify war, hate, intolerance, nationalism, and rise of police and surveillance states.

In Avant-garde Videogames: Playing with Technoculture (2014), I describe how avant-garde political art and games blend domains as well as problematize dichotomies, such as safe/dangerous, private/public, sacred/profane, in transformative ways. An iconic example is Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece (1964-1966), which she first performed in 1964 in Japan. The artist walked onto a theater stage, knelt down and placed a scissors on the stage nearby. All she said was “cut”. One by one, audience members got up from their seats and proceeded to cut off pieces of her clothing. When Ono was stripped down to her bra and underwear, the audience stopped cutting and everyone simply sat in their seats. The next year Ono performed Cut Piece at Carnegie Hall in New York and the audience behaved differently. For example, an audience member menacingly walked around Ono brandishing the scissors in a threating way and proceeded to cut off her bra and underwear, resulting in a symbolic kind of rape. Challenging popular constructs of risk society, Cut Piece blends intimate space with public spectacle. It places trust in the hands of strangers. Ono hopes they will treat her with respect but it is ultimately each person’s decision how to treat the silent, vulnerable artist. The piece demonstrates how to risk one’s dignity publically to achieve more social trust.

The game BorderXing Guide (2002-2003) enables players to engage the risk of arrest through acts of political dissent. Developed by Heath Bunting and Kayle Brandon and sponsored by the Tate Gallery London, BorderXing Guide was an attempt to “delete the border” by hacking national boundaries. Deployed from 2002-2003 the game emboldened and aided players crossing the borders of European countries surreptitiously and illegally. Only accessible in tactical geographic locations, an online database conveyed procedures for crossing borders undetected by police and military. By throwing a colossal magic circle over European states, BorderXing Guide players could engage in sociopolitical dissent through the playful traversal of space.

Figure 3 A Pac-Manhattan player dressed up as Pac-Man runs across a street to avoid ghost players. Image retrieved from http://pacmanhattan.com

Pac-Manhattan, developed in 2004 by students at Tisch School of the Arts, New York University, is a location-based game in which players run around Manhattan. A player dressed up as Pac-Man tries to avoid other players dressed up as the ghosts Blinky, Inky Pinky, and Clyde. Pac-Manhattan players run through traffic and crowded sidewalks, risking potential citation by police, physical injury from moving vehicles, and social judgment from playing wildly and disruptively in public. Beyond allowing players to engage in various kinds of risk, playing Pac-Manhattan exerts a sociopolitical force because it reclaims public space as a venue for whimsical play.

I hope this brief look at other risky games provides some perspective on the genre. Rather than provide a formula to design risky games, I will simply offer this. Technoculture increasingly funnels our proclivities for play into safe and manageable mechanisms, which we then increasingly take for granted as the way things are. We swipe right on sex partners the same way we match three, retweet, order food, and vote. Our day is a long, safe mosaic feed of playful choices and tiny surprises. Social media becomes a great game as does the political process, dating and everything else. As our daily choices seem less consequential the real world seems more so, more volatile, more unpredictable, more terrifying from climate change to terrorism. Every election becomes the most important election in history. There is a growing gulf between the way we inconsequentially and safely play in the world, and the dire rhetoric and perceptions we have about the world. The more we can connect the two through risky play the more we can live and perform in the world in ways that are earnest, yearned for, and transformative.

Conclusion

Games that incorporate actual risk by design can help us overcome delimiting habits, norms, and laws. They help make us resilient to manipulation through fear. Riskier games expose our self-imposed limitations concerning risk and provide opportunities for us to grow past them. They encourage us to handle greater uncertainty with playful grace. This opens up our world to be fundamentally reconfigured through play. The more we risk of our world and ourselves the more we can reveal, examine, and reconfigure. The types of risk and the aspects of the world that we transform may have to do with physical safety and the sense of our body’s fortitude; or our conceptions of public space and the appropriate kind of behaviors that space affords; or legal constructs of space from national borders to the demarcation of private property; or they may be more narrative or personal in nature—allowing players to face unique fears of humiliation, specific traumas or potential injuries. Whatever the case may be we should design more of our games to be broken and risky in myriad ways if we want to advance the medium of games as well as realize and reclaim the real potential of play that has been disappearing in our overly fearful risk society.

Review excerpts

Click here to read excerpts from the reviewing process.

References

BorderXing Guide, Bunting, H., & Brandon, K., England, 2002-2003.

Brown, S. (2010). Play: How it Shapes the Brain, Opens the Imagination, and Invigorates the Soul New York: Avery.

Brutally Unfair Tactics Totally Okay Now (B.U.T.T.O.N), Copenhagen Game Collective, Denmark, 2011.

Bust A Cup, Schrank, B., & Gabor Jr., B. USA, 2014.

Cut Piece, Ono, Y. Japan, USA, & England, 1964-1966.

Erikson, E. H., & Coles, R. (2000). The Erik Erikson Reader. New York: W. W. Norton and Company.

Fusselman, A. (2015). Savage Park: A Meditation on Play, Space, and Risk for Americans Who Are Nervous, Distracted, and Afraid to Die. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Hans, J. S. (1981). The Play of the World. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

Huizinga, J. (1970). Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture. Boston: Beacon Press.

Jackass Number Two, MTV Films, Dickhouse Productions, USA, 2006.

Jackass: The Movie, MTV Films, Dickhouse Productions, USA, 2002.

Lee, N. (2006, September, 22). The Joy of Self-Inflicted Trauma. The New York Times. Retrieved from: http://www.nytimes.com

Pac-Manhattan, Bloomberg et al. USA, 2004.

Raley, R. (2009). Tactical Media. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Schrank, B. (2014). Avant-garde Videogames: Playing with Technoculture. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Schrank, B. (2014, September 22). Bust A Cup video. Retrieved from http://brianschrank.com/games.htm#bust.

Sutton-Smith, B. (1997). The Ambiguity of Play. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Virilio, P. (2006). Art and Fear. New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

Wilson, D. (2011). Brutally Unfair Tactics Totally OK Now: On Self-Effacing Games and Unachievements. Game Studies, 11 (1).

Author contacts

Brian Schrank – bschrank@cdm.depaul.edu

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.