Vicki Williams (University of Birmingham)

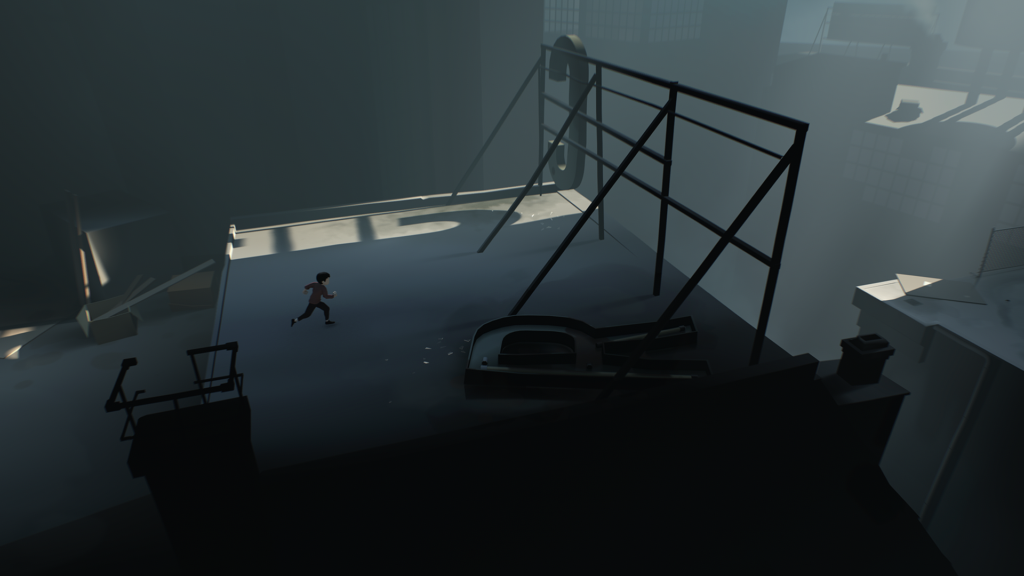

Figure 1 – Screenshot taken from Inside (Playdead, 2016). All figures included in this article are courtesy of Playdead

Abstract

Videogames and their systems of play are continuously defined through their slipperiness, i.e. their affective capacities that attend to realms beyond the human, producing agencies which escape and exceed human grasp. Drawing from interdisciplinary perspectives of agency, phenomenology and affect theory, this paper will conceptualise Unhuman Agency, and its emergence in Playdead’s 2016 videogame Inside. The paper will argue that the mutations of the human subject in the game mark a distinct movement towards various kinds of material slipperiness which challenge human/player agency. This paper will look at the ways player agency is continually at odds with the world inside, and how this lack of agency opens up aesthetic, social, and political tensions present within the game-world. Via Unhuman thematics, Inside represents a world of authoritarian agencies which implicate various bodily rhetorics (Foucault, 1975), requiring players to un-learn agency and common gaming mechanics to adapt to the unique logics and movements present within the game’s eerie landscape.

Keywords: Unhuman agency, affect, embodiment, phenomenology, Inside

Videogames toy with agency. The medium’s affordances when it comes to player agency are rich and entangled, creating dialogues between play and programmed systems. Yet, unanticipated agencies emerge out of and beyond the programmable corners of videogame systems. There are multiple interactions and interrelations between a game’s narrative, environment, material components and player embodiment that see control and agency dispersed between ontological layers. Such forms of agency emerge procedurally when (human) player and (nonhuman) system interact with one another in unanticipated ways. As one aspect of opening new discourses around the ways agency emerges as an aesthetic, social, and political factor within videogame play, this article will consider the ways that a lack or distribution of agency reveals legitimate and novel tensions. The 2016 puzzle platformer videogame Inside by Playdead will be explored here in order to demonstrate the ways agency is distributed between the game’s central text, subtexts, and physical interaction with the gaming hardware. Such encounters, I will argue, see a coming-into-contact with the Unhuman. I will begin by outlining some of the key scholarship concerning agency as it is distributed between human and nonhuman actors. I align this with the article’s approach to the unhuman. The unhuman, I want to suggest, is an underexplored facet of videogame subjectivities and the ethics of gameplay.

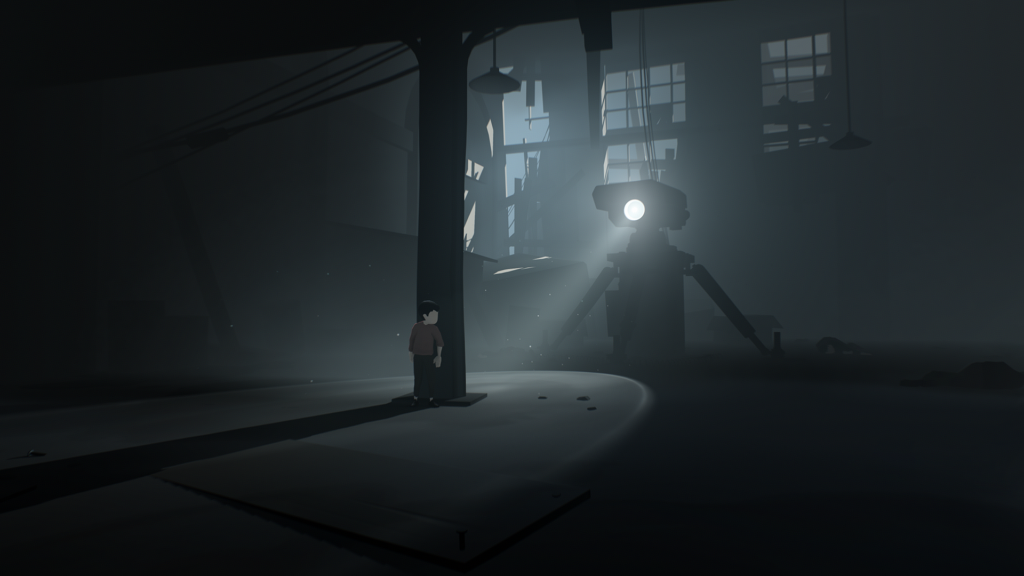

The game Inside, released cross-platform by Playdead in 2016, is an eerie puzzle platformer which centres around a young boy who moves through a dark, unforgiving world of complex mind control systems and terrifying encounters with unsettling creatures. All of the subjectivities present within its world, including the boy, are constantly monitored by non-human entities: cameras, computer networks, and the game system itself. The visual design and aesthetics of the environments hint at the dark and eerie worlds the game represents: not only is the player given very little information about the storyline the game follows, but they are also given little sense of the central agents who are in control of the world depicted. As a puzzle platformer, the game intends for the player to make mistakes in order to solve the puzzles in the environment the next time around. Over the course of the game, the narrative implicates various subjectivities, and its puzzles evolve across various human labour practices. The puzzles within the game adjust with the type of environments represented: from rural fields and abandoned farm buildings towards desolate, Fordist industrial spaces (Figure 2). These include large factory buildings which house conveyor belts, levers, and creaking pipelines. Yet, it is also clear that Inside draws attention to the systems at play beyond the player’s immediate perceptual experience. Within its temporal framework, Inside captures various mutations of the human subject over time, the societies of which they are part, and the technologies they interact with and become part of, marking a revelation of Unhuman agency. Elements of unhumanity reveal the more slippery and affective relationship the game initiates beyond the bounds of absolute player autonomy; there is simultaneously evoked a sense of control, but a control that is constantly pulled away by actors in the gameworld, and the gaming system.

Figure 2: The boy explores a farm in Inside (Playdead, 2016)

Figure 2: The boy explores a farm in Inside (Playdead, 2016)

My analysis of the game Inside will be informed by a new materialist perspective, a vantage from which player agency and its importance to fluid gameplay is disrupted through consideration of its complex affective tendencies. The multi-sensory nature of Inside has been explored in much of the writing and reviews of the game, particularly in the ways the audio tracks reveal elements of the narrative 1. Yet, little has been done on the intricacies of the affectivity of the game, the kind of emergent feelings produced by its mechanics, and the ways its narrative truly unsettles player agency. Alternative logics and models of physics are revealed through strange experiments contained within the gameworld. There are human corpses tied to chords that float upwards underwater, and other gravitational forces which push rather than pull; such forces are replicated through subtle triggers that emerge out of the hand controller. In one section, the player must shelter the young boy from the deathly, rupturing force of a sonic boom experiment: should the boy come into contact with the vibrational force which is omitted from the mechanism, his body explodes and flies towards the screen in shards of flesh. This moment is affectively transient, mimicked by vibrational feedback in the controller, and unsettling sounds of rupturing flesh as it perceptually gets flung towards the player. An exploration of the new materialist framing of intra-action might more accurately capture the nuanced interplay of agencies beyond the player that are present both in the game’s central plot, and its material interactions with the player. The formulation of intra-action emerges in the work of Karen Barad. Her investigation of cross-ontological agencies sees a decentring of the human subject. In her 2017 work Meeting the Universe Half Way, Barad reads the interactions between human and non-human agents through what she calls “agential realism”. She defines this as:

An epistemological-ontological-ethical framework that provides an understanding of the role of humans and nonhumans, material and discursive, and natural and cultural factors in scientific and other social-material practices, thereby moving such considerations beyond the well-worn debates that pit constructivism against realism, agency against structure, and idealism against materialism. Indeed, the new philosophical framework that I propose entails a rethinking of fundamental concepts that support such binary thinking, including the notions of matter, discourse, causality, agency, power, identity, embodiment, objectivity, space, and time. (Barad, 2007, p.32)

Barad’s framework of agential realism analyses modes of agency which are spread amongst “intra-acting” actors. By this, Barad suggests that agency resides across matter, discourse, causality, power, identity, embodiment, objectivity, space and time— between both human and nonhuman actors. This reshapes the concept of agency within liberal humanist thinking as “the ability to act based solely upon one’s own free will” (Tulloch, 2014, p.342). There is a focus in Barad’s work on the act of ‘becoming’, as opposed to a fixed subject or object who acts on their own accord. She states that “matter is substance in its intra-active becoming—not a thing but a doing, a congealing of agency” (Barad, p.151). The focus on matter enables new considerations of the possible expansions of agential enquiry; matter, as substance, is continually forming through the congealing of multiple agents. The game Inside, through its depicted tones and textures, places a strong emphasis on this congealing of agencies through various subjectivities in its world. I argue here that in the particular context of the game, this reveals the “unhuman” at its core. The game propels its player towards a rupturing of agency and embodiment. The Inside referred to in the game’s title is potentially an outside: the revelation of subjectivities which exist on the edge of human phenomenology and cognition. Inside represents not just the co-emergence of the human and nonhuman, but the production of an entirely new unhuman subjectivity. This videogame marks specific mutations of a specifically human subjectivity, and marks a shift in emphasis from human/player agency, towards a dynamic and intra-active network of agents.

Post/Non/Unhuman

The unhuman serves a particular purpose within the game Inside, in that it provides a framework of compromised agency which is central to the game’s narrative. However, before venturing into the particularities of the unhuman in Inside, I want to establish where the figure of the unhuman draws on, and differs to, the more commonly found categories of the nonhuman and posthuman. The unhuman is yet to be rooted in games scholarship – and here I hope to unite the topics of unruly agency and affect through the horrific dimensions of unhumanity. The prevalence of the posthuman, and the field of posthumanities, indicates the desire of the humanities to challenge the centrality of a generalised human subjectivity in its enquiries. The posthuman/posthumanities push beyond common figurations of the human, considering underexplored objects, things, animals and oftentimes “othered” beings that extend critical enquiry beyond the humanist subject. In their introduction to the Posthuman Glossary, Rosi Braidotti and Maria Hlavajova offer rich insights into the capacity for the posthuman to “critique […] the humanist ideal of ‘Man’ as the universal representative of the human” (2018) and even to “contribute to and explode the concept of the human” (p.3). The posthuman also has its roots in cybernetic discourse (e.g. Hayles, 1999), marking the convergence of humanity and the machine. The nonhuman is somewhat concurrent to the aspirations of the posthumanities, given its capacity to open up considerations of things and beings which are not captured under the category of “human”. Agency plays a pivotal role in scholarship on the nonhuman, in the ways that it opens up the ways we conceptualise agency as interconnected and dispersed, beheld by humans, objects and animals alike. The post and nonhuman are oftentimes associated with contemporary games studies, in the ways that they enable us to understand the rich systems that videogames enact. Daniel Muriel and Gary Crawford argue that “videogames help us to visualise the nature of agency in contemporary society as a posthuman, assembled, and relational process.” (2018, pp.9-10). They suggest that the distributed agencies enacted by and through videogames enable an affective and embodied understanding of the ways objects, bodies and software peripherals all enact change. This approach is communal, yet the unhuman makes communality strange. The unhuman challenges the unity of things and rather asks where they pull apart.

The unhuman is an unruly being. It marks a brute, embodied materiality—a mutation, and an alienation of humanity away from itself. In a sense, the kinds of mutations captured through the figure of the unhuman mark a temporality after the human – where traces of the human subject are eerily present on an elemental scale (for example, flesh), but mutate into new and unsettling subjectivities. Dylan Trigg’s work on the unhuman places the figure specifically at the core of horror and emerging phenomenologies “in which the gaze of human subjectivity loses its privileged place” (2014, p.3). Trigg locates the unhuman at the cusp of traditional phenomenology, where new subjectivities emerge which challenge traditional notions of what it means to be human. In many ways, Trigg’s formulation sees an embodied emergence of human and nonhuman agents commingled. Trigg states that the unhuman enacts:

A collision of the human and non-humanity inhabiting the same body, with each aspect folding over into the other…The subject…is depersonalised through an exposure to the alienness of matter. What remains is materialised abjection. (pp.8-9).

It is here, I argue, that the strange, affective contours of the unhuman emerge. Marking a new subjectivity, the unhuman sees multiple agents folding into one another, an embodied being that marks the slippery and inarticulable enmeshings of human and nonhuman.

Within unhuman subjectivity lies a new focus on the weird contours of human embodiment, its messy articulations and limitations. I have argued elsewhere that the sensations of the loss of control during gameplay allows for the emergence of unhuman forces, where the player senses weird affections that manifest within their own bodies 2. Dylan Trigg’s particular emphasis on horror and the uncanny sees “alien material” as a central facet of coming-into-contact with the unhuman—where suddenly the body does something unanticipated that makes us acknowledge its messy materiality. This kind of sensation can emerge when game systems do something the player did not anticipate, where there is an incapacity to behold the agency to maintain full control over their own actions. The unhuman can be found when intra-actions follow a slippery and unanticipated connection between human (subject; player) and nonhuman (object; gaming system; material hardware).

Elsewhere, contemporary scholarship on the figure of the unhuman focuses centrally on its implications and articulations of agency, considering the challenges the unhuman poses to the more widely explored subjectivities in humanism and posthumanism. Daniel Cottom’s Unhuman Culture argues that the unhuman is that which is “foreign to the definition of humanity” marking the “alienation of humanity from itself in the very act of positing itself” (2006, p.xi). For Cottom, the unhuman poses a definitional dilemma: it uproots the meaning of humanity and human subjectivity, alienating it from itself. Cottom argues that the unhuman challenges the idea that agency is, or ever was, distinctly human, stating:

identity then would appear to be wrought by the impersonal agencies of economic, technological, political and ideological forces and structures. (p.x)

These impersonal agencies mark the intra-active relations between human and nonhuman systems, the visible and invisible elements that structure experience. In Human No More: Digital Subjectivities, Unhuman Subjects, and the End of Anthropology (2012), Neil Whitehead and Michael Wesche link unhuman subjectivity directly to digital technologies and the ethical dilemmas attached to the ways they reconfigure what is human (p.11). Whitehead and Wesche look at the new forms of marginalisation and oppression created by technological monopolies, where digital connections produce new forms of sociality beyond traditional social formations.

‘The Huddle’ as Congealed Unhuman Agency

The unhuman subjectivities found within Inside mark fleshy and affectively disturbing subjects that cross into alien territories. The game, in many ways, attempts to mimic the affective coming-into-contact with the unhuman through a layered narrative which bleeds between representation and the player’s material interactions with its world. This becomes central at the game’s finale – where the sporadic allusions to unhumanity throughout the game congeal themselves into what Playdead label as ‘the huddle’.3 The huddle is an entity discovered by the central avatar of the young boy at the end of the game. In the words of the game designers, it is “a compound humanoid blob of muscle, fat, skin and bones” (GDC, 2018). Playdead note that they took inspiration from various phenomena including crowdsurfing, a cluster of individuals where hands share a common goal. Visually, the huddle looks like a huge compound of flesh comprised of human body parts that have been mingled together. The huddle, I argue, is unhuman precisely because it represents an alienation of humanity into materialised abjection; it is horrific, it is strangely affective, and it resists agency on the part of the player and the gameworld.

The huddle is initially encountered by the player upon locating a vat within a building comprising computer networking rooms and laboratories. Human figures in lab coats and business wear surround the vat, gazing in at the huddle (which remains hidden until the young boy gets sucked into the vat and swims towards it). This is the suggested Inside made evident in the games title – the centre of a vast corporate entity whose networks remain obfuscated throughout the game’s entirety. The huddle is attached to a pumping mechanism within its enclosure, as if it is being used as some kind of energy source. This is the functioning source of the unhuman network at the heart of the game. The game implies that the huddle has been created by an underground establishment, in order to power the strange experimental puzzles the player participates in throughout the rest of the game. The experiments are predominantly focused around mind control – where the player encounters a number of animals, zombie-esque figures and technological entities which appear to be under the control of a powerful and dystopic hidden agency. Essentially, the game operates in a way that maps new revelations during its course, as opposed to giving any direct and directive diegetic information to the player through cut scenes and dialogue.

The huddle is the heart of a vast control network which dictates the behaviour of everything the player has witnessed throughout the game. Such a network, according to Alexander Galloway and Eugine Thacker’s approach in The Exploit: A Theory of Networks (2007) can be read as an emergence of the unhuman through network control. The huddle necessarily represents an aggregate life form which sees agency extend beyond the human subject, and into a strange, visceral network of fleshy matter. Galloway and Thacker note that:

Network control ceaselessly teases out elements of the unhuman within human-oriented networks. This is most easily discovered in the phenomenology of aggregations in everyday life: crowds on city streets or at concerts, distributed forms of protest, and more esoteric instances of flashmobs, smartmobs, critical massing, or swarms of UAVs. All are different kinds of aggregations, but they are united in their ability to underscore the unhuman aspects of human action. It is the unhuman swarm that emerges from the genetic unit. (p.41).

Through this approach to networks, the unhuman is revealed to be always-present, always potential, emerging at the point of new synergies that are impersonal and intersubjective. The swarm, as one unhuman unit, marks the dissolution of human subjectivity towards an aggregate phenomenology. The huddle is inspired by the unhuman swarm, in the way that it still maintains an elemental human feel, but produces an entirely new aggregate entity. Galloway and Thacker argue that unhuman figurations capture the “tension between unitary aggregation and anonymous distribution, between the intentionality and agency of individuals and groups on the one hand, and the uncanny, unhuman intentionality of the network as an ‘abstract whole’” (p.155). The Exploit sees the unhuman as a marker of the underlying agency of networks that monitor and control human subjects. This analysis of networks reveals the nonhuman elements that form our understandings of human subjectivity, as it is (re)produced through digital technologies in the form of bits and atoms. The unhuman reveals and breaks down the valorisation of the human subject as absolute agent, and allows access to otherwise hidden agencies which emerge alongside human action on both individual and collective levels. Where Galloway and Thacker maintain focus on human-oriented networks, the network present within Inside fundamentally circulates dystopic mind control functions that produce its specific forms of unhuman agency.

The ethical dimensions of the unhuman are arguably the central force within Inside: players of the game are forced to consider the world’s underlying systems, the ways that the technologies present within its world reconfigure the human subject, and the inherent implications of these reconfigurations. The huddle is the subjectivity which powers the network it is controlled by. Enclosed within a gigantic vat, attached to a large mechanical chord, it appears that brute matter is the central energy source to the intricate systems embedded within the world. Viewed in this way, the world of Inside can be seen as one giant network-body. Its entanglements of wires, generators, and complex mechanisms all link back to the huddle. The huddle is the brain at the core of the system that it is being manipulated by. The boy is absorbed into its mass of flesh – at which point the player moves through the world as the huddle. As the boy becomes part of its “beastly body” 4, it breaks out of its glass cage; the humans that surround it run in fear. It is here that a change of agency is marked by the bodily rhetorics of the huddle, where the player must control the disorientating and unbalanced mound of flesh as it crashes through glass and squeezes through small doorways. The huddle utters eerie moaning sounds as it moves, replicating the sound of deep, distorted human groaning, which indicates a conflicting sense of pain from something that was once human, but is no longer. The affective tie the player has with the huddle is marked by a fluid and unstable link between the actions they take on the control pad, the feedback sent through the hand controller, and the movement of the huddle on the screen. There are kinds of subtlety involved that the player must learn in order to balance its unhuman fleshy substance as it crashes through the gameworld. Though the player now controls the mass of flesh, there is a sense that its agency remains somewhat untethered. The game challenges the ethics of completing its puzzles as a means to its players achieving satisfaction. Rather, it makes the player consider the ways they are implicated, and what role they have played in the events that unfold having participated in its world. The unhuman networks mask the hidden agents at the game’s core. Though the huddle is horrific and yields its own agency, it is seemingly bound by the creation of a vast corporate entity that engineers mind control systems in order to produce obedient subjects.

The game’s aesthetic design depicts all of its human characters as abstract and faceless. There is no capacity for human emotion to be rendered visible; instead, the game places focus on sound and movement to relay emotional cues to the player, and influence them to action. The avatar that the player controls from the start of the game is perceivably human: a young boy wearing a red jumper who begins by tumbling from out of shot into a rain-sodden field. Though the boy is faceless, his bodily rhetorics – i.e. the manner in which he moves – relays useful information to the player. For example, when the boy is in danger, he will begin to sprint hectically and his breathing becomes heavy and panicked. Such actions are motivated by signifiers in the gamespace, including other people, animals, and objects which pursue him. This is initially learnt by the player in its opening scene as he is approached by other ‘human’ actors. Within the eerie, dark landscape of a wet field, a set of car headlights emerge out of the foggy backdrop and two men exit the vehicle. Without any action on the part of the player, the boy looks towards the car and begins to breathe heavily. When the player urges the young boy forward, his movement transitions from measured jogging towards a panicked sprint. The men then ran towards the young boy, and the player must tackle a number of obstacles to avoid being captured by the men; if he is captured, the boy is killed. This is something the player only learns if they do not manage to escape the first time round. All of the boy’s movements relay subtle feedback through the hand controller, and this alters according to the kinds of environment he moves through. The camera’s pans, framing and angles are predominantly fixed, save for some parallax elements, yet at key points the vista shots zoom in and out in order to reveal visual cues that aid the player; these cues, along with other audio-information, reveal subtle hints of how the player should respond in certain situations. The player, throughout most of the game, is forced to imagine the game’s plot, as no direct information is given to them about the wider narrative premise. The player feels a sense of responsibility toward the boy, but has little control over the wider structures – why he must survive, where he is going, and for what purpose. There is a sense of evolution within the objects the boy can interact with as the player progresses throughout the game, all of which hint at various “bodily rhetorics” associated with traditional working models. I am taking bodily rhetorics here from the work of Michel Foucault (1975), which captures the ways subjects move, the gestures they make, and the efficiency through which they respond to institutional order. There is a sense that Inside draws attention towards the bodily attunement of the young boy in various institutional environments, which constantly and consistently shifts as the game progresses. Where the beginning of the game is primarily located outside in rural, farming landscapes, the end of the game marks an absolute rupturing of bodily subjectivity into the unknown and eerie rhetorics of the Unhuman huddle.

The agency communicated to the player through the young boy differs from that of the huddle, in that it feels slippery to control: the huddle is a subjectivity which escapes and exceeds the human player’s grasp. By ‘slippery’, I not only allude to the huddle’s fluid mechanics and movement through the gameworld, but the replication of its affective surfaces via the player’s embodied interaction with it. For example, though the player pushes the huddle forwards, it moves with its own fluid and unhuman momentum. Its limbs stretch out in various directions, it stumbles, condenses and expands its own fleshy substance. The affective sensations of moving the huddle replicate the eerie organicity of its bodily parts. This affective modality of interacting with a videogame marks the medium’s capacities to attend to realms beyond the human, producing new agencies which escape and exceed human grasp. This sense of the ungraspability does not necessarily reference a literal holding onto something like a hand-controller, it allows for a reconsideration of valorised player control as the central means for progression through a gameworld.

Figure 3: as the player pushes forward, the running boy gains momentum in Inside.

Figure 3: as the player pushes forward, the running boy gains momentum in Inside.

Agency, Game Aesthetics and Weird Affect

Inside resists the use of representations of emotion to convey information to its players, instead programming affective cues to prompt player action. The game requires that the player has an embodied relationship with the gamespace: as Aubrey Anable notes, the feel of a game “is directly linked to the affective circuits that touching opens up between representation, screens, code, and bodies” (2018, p.37). The game’s affective dimensions enable the player to gain some insights into the idea that the young boy is being hunted down by some kind of anonymous institution. Given the lack of intradiegetic information relayed at the beginning, there is no emotional attachment – but certainly an affective one.

Videogames act as unique mediums for eliciting specific forms of affect. The capacity for players to be touched by videogames has been explored by a range of scholars (Ash 2013; Shinkle 2005; Anable 2018) all of whom consider the contact produced between the body, representation on screen, gaming narratives, software, and hardware. James Ash (2013) argues that affect can be aligned with the ways players become somatically attuned to the medium, incorporating gaming hardware as part of their apparatus in order to achieve desired actions within the gameworld. Ash notes that specific design elements negotiate the “affective and emotional engagement” players have with games (p.28). Eugénie Shinkle pushes beyond the capacity for game design to mediate affect, arguing that players “possess subrational agency” which enables lateral and unpredictable responses to perceived environments. Shinkle argues that “games actualise affect in ways that designers (whatever their motives) do not always anticipate.” (p.6). Aubrey Anable (2018) notes that affect can be read as a specific orientation towards representations, arguing that game studies has seen a shift away from emergent gameplay, towards emergent feelings. Anable reads videogames as mediums which enact “specific affective dimensions, legible in their images, algorithms, temporalities, and narratives” (2018, p.7). Across the spectrum of approaches aligning videogames with affect theory is a questioning of the ontological boundaries between players, programming, representation and material hardware. Whether intentional (attunement; incorporation) or unintentional (subrational response), our affective responses to videogames necessarily implicate various human and nonhuman agents.

For the sake of this article, it is necessary to consider the ways in which games might complicate attunement and incorporation, in the ways that they produce sensations for the player of not quite being in control. Some games produce unique affects when agency is, or feels like it has been, stripped away from the player; this can be both embedded in its programming, or occur through emergent play. Horror games, in particular, are notoriously sites for experiencing compromised agency. Tanya Kryzwinska notes that the dynamics of being in and out of control in horror games see the emergence of affective attributes that “link deep to the structure of games, provided by their programming” (Kryzwinska, 2002). Toying with agency is particularly relevant to videogames, in the ways that agency can be pulled between multiple actors including player, hardware, narrative, and code. However, the particularly strange, embodied affects produced by compromised agency in games remains underexplored. When games pull between an ontological here and there, this can leave the player feeling uneasy—it can evoke strange satisfaction and unanticipated thrills. Weird affects seep out of the programmable corners of videogames: they are not necessarily predictable for players when they participate in their virtual worlds. Videogames have the unique potential to make us feel weird. This could, for example, occur when a game glitches, momentarily resisting both the control of the player, and also its embedded programs and control systems. Games become weird sites when they do something that neither player nor programmer could predict. They can also make their players feel strange through their unique aesthetic and representational capacities. Videogames have always allowed for the depiction of unsettling and inarticulable subjectivities that operate via logics that are beyond the quotidian lifeworld – namely, alternative worlds that give rise to new beings which go beyond the human subject. In the case of Inside, I argue, weird affects emerge through the game’s depictions of unhuman subjectivities which are inherently strange and unsettling.

Mind Control

After considering the unhuman in relation to its affective contours, I want to turn specifically to the circulation of unhuman elements in the game via its hidden mind control networks. Here, I argue that the diegetic representations of agency pour out of the gameworld, and are mirrored by the player’s own relationship with the avatar’s they control. The parasitic entanglements of agency overtly represented in the game bleed out of, and slip beyond the plot, as they simultaneously frame the relation between avatar and player. The mind control structure is first hinted at earlier in the game, when the player moves the young boy through a field full of scattered pig corpses. All of the corpses are being consumed by small parasitic worms. Moving past the heap, a living pig charges towards the boy; if the player does not steer clear of its path, the boy gets trampled by it. The pig groans uncomfortably as it moves, and follows the young boy in whichever direction the player moves him. Upon closer inspection, it appears that a worm is attached to the pigs head. The animals are being controlled by some kind of genetically modified creature that dictates that they too must try to sabotage the boy as he gets closer to the game’s Inside. Such parasitic elements of Inside have been discussed by Andrew Bailey in his paper ‘Authority of the Worm: Examining Parasitism Within Inside and Upstream Colour’ (2018). Bailey notes that parasitism “functions as a tool for the boy to make subversive use of the same systems that are being used to take control of his world” (p.49). There is a multidimensional agential problem at the core of the game, where the player must manipulate the boy to progress, whilst the boy enacts manipulation onto a number of figures within the game. In the early stages of the game, such agency follows the rules of bodily rhetorics that function on a primarily instinctual level – where there emerges a threat, run or hide from it. The boy’s movement is fairly self-explanatory to begin with, and the player must simply follow the multisensory cues provided within the environment in order to solve the puzzles. Yet these puzzles become more and more complex, as the dimensions of the networks in the game reveal themselves.

Figure 4: Screenshot from Inside (Playdead, 2013) in which the boy is monitored thorough a surveillance system.

Figure 4: Screenshot from Inside (Playdead, 2013) in which the boy is monitored thorough a surveillance system.

As the player navigates through various spaces, the camera pans in and out to reveal backdrops in the distance of masses of drone-like human bodies, marching outside the buildings. The player gains brief visual insights through small crevices and windows of the lines of unhuman bodies, moving in perfect synchronicity towards an unknown location. Not dissimilarly to the mind-controlled pigs earlier in the game, these figures move as if they are being controlled by something. They ignite unsettling feelings during gameplay, because the player has very little sense of who or what these figures are, and who they are being controlled by. Clambering across rooftops and sliding down pipelines, the young boy eventually falls through a gap in the roof, and stumbles into a line of the drone bodies as they drudge forward through a space where they are monitored by multiple surveillance cameras and figures wearing lab coats. These drone-like bodies lack any kind of humanity, beyond their being human bodies. Their bodily movement differs, for example, from those they are being monitored by: animate human-beings, with lifelike qualities who are wearing smart business attire and lab coats. As they stand taking notes, below the overbearing gaze of an inscrutable surveillance camera, the player must learn to adjust to the rhythm of the figures, moving perfectly in time with them. If they fail to do so, a claw emerges from the surveillance camera, dragging the boy out of line and presumably to his death. The player, in other words, must adapt the boy’s bodily rhetoric within the game to the rhythm and motion of the unhuman figures it portrays. The player must affectively respond to the intense situation they are thrown into, and learn as they go along. Any action that occurs outside of the synchronous rhythm of the system warrants death, and the puzzle restarts. Such unhuman bodily rhetorics mark the emergence of the unhuman subject under “the individualising fragmentation of labour power” (Foucault, p.148) within the gameworld; each body becomes a unit that is monitored under the premise of a kind of lifelessness. Any hint at “humanity” or messy movement results in a removal of the body. The line, then, marks the surveillance of efficiency under the unknown institutional order that characterises the core of the game’s narrative system. As such, affective embodiment is seemingly eradicated, a shift towards a “bodiless reality” (Foucault, p.148) where movement is dictated by the narrative’s central political machine. The unhuman presented here manifests a bodily docility. This, in and of itself, marks an uncomfortably affective player experience: the strange movement of the docile unhuman bodies is tense and unsettling. Yet the player must adjust their control accordingly in order to fit this unhuman mould.

As the game progresses further towards the Inside the game’s title alludes to, it becomes more evident that these unhuman figures are being controlled by an ominous and parasitic mind control system. There are increasingly frequent encounters where it is evident that more “human” bodies are surveilling and monitoring the “unhuman” bodies, and this is primarily revealed by the bodily rhetorics each of the bodies enact. The unhuman bodies slouch and stumble forward, their faces not even looking in the direction they are walking. They seemingly resemble the undead, the zombie – a kind of regurgitated stumble. They represent a compromised form of (un)humanity that is produced in order to fulfil a system functionality, created in order to be completely unconscious and docile.

Discovering Subtexts: Further Dimensions for Agential and Ethical Enquiry?

Within all the strange and disorienting puzzles that the player must solve, there remains a slippery sense of agency that ties to the ethics of play; that is to say that the player has to use the docile unhuman bodies depicted in order to solve the puzzles and move onto the next stages. Despite the fact that there is an ominous control system at play, the player themselves participates in this control system by utilising their own agency over the unhuman figures whose agency is being compromised. In one particular section of the game, the boy moves through an abandoned mining shaft, and is followed by unhuman miners who seem to be drawn to him. The player must escort the miners through the shaft, using them as material mass to trigger a platform that unlocks the door to exit. When the player has recruited 20 miners, all of whom follow the young boy in whichever direction he moves, the entrance into the next part of the game unlocks. Whilst the miners remain in stasis on the platform, the boy runs towards the exit, leaving them abandoned in the bleak underground space. The game often sheds light on the injustices of its own mechanics, where the player must participate in the abhorrent system the game portrays, and the subjection of bodies that are neither living nor dead is the central concern of its narrative.

Adding further dimensionality to the intra-active agencies depicted in its world, should players participate in its hidden and sedimented subtext, Inside goes further to suggest that the young protagonist might be unhuman, too. Though the boy participates in the manipulation of other bodies in order to progress, the game implies that the same manipulative tendencies are built into the player’s own control over the avatar protagonist. A number of yellow wires are seen during certain parts of the game. Should the player follow them to their source, straying off the path toward completion, they come to small generators that the boy is able to unplug. When unplugging the generators, they spark and force the boy to retreat backwards. Such an act is made to feel as though it is a form of resistance, not just in the way it appears to be a breakage of the diegetic network, but also in that it requires player to venture away from the intuitive paths presented. All of the generators are hidden away in nooks and crannies that veer away from the central path towards the game’s inside. This oftentimes requires that the player simply see if turning around or jumping through small enclaves will allow them to gain access to hidden areas. If the player manages to locate all of these hidden generators and unplug them all, the player can then load and return to one of the earliest scenes in the game where the boy runs through a wheat field. Hidden amongst the high grass lies the entry to an underground hideaway. The player can embark down a step ladder within the opening and find themselves in an abandoned bunker. If the player wanders through the space, they locate a pad; opening the door leads onto an extensive tunnel where a central power source can be located. Seen within the background is a large mind control helmet that is infiltrated with wires. When the player unplugs this final power source, the mind control device in the background explodes. At the same time, the boy’s body slowly slumps forwards as if he too has been unplugged – and the game ends. This alternative ending adds even further dimensions to the agencies implicated in the game: either the power prevents the player from controlling the boy any longer, or the actions the boy takes might have been dictated by another unknown agent the entire time. This would imply that the boy might have actually been the central unhuman subject of the game from the outset. The implication that the boy is also being controlled inadvertently implicates the player in the game’s dystopian network of actors. The games layers unfold outwards; though the game purposefully leaves many questions unanswered, the player is revealed to be the hidden force behind the wired systems and networks at play.

Inside has the unique capacity to make us feel unhuman not just through its representation of unhuman subjectivities, but through our being part of its morbid, unhuman system. Every seemingly resistant act or attempt to break or reveal the hidden networks within its world only leads the player to feel responsible for the cruel fate of other subjects. Even having reached the game’s Inside and solving puzzles in order to break the huddle out of the eerie buildings and infrastructures, leads to a dead end. The game ends with the huddle rolling out onto a beach, where its grotesque flesh lays bare against the moonlight. Momentum is halted, and the credits roll, leaving no sense of whether the player’s actions led to any retribution. Though this might seem to be an almost disappointing ending, Inside asks for a shift of focus – away from the sense of fulfilment achieved through progress and ‘doing well’ in a game, rather towards the feelings gameworlds are able to produce. Feelings move from fear to frustration, monotony to excitement, simplicity to impossibility, fulfilment and emptiness. Though all games necessarily implicate some of these feelings, Inside asks of its players to truly acknowledge how it feels to be played. This is supported by the strange intra-actions between its components: the vibrational feedback emitted by the hand controller, the unsettling mechanical sounds embedded in its settings, or the splatting of the huddle as it crashes from tall heights. Here, I have argued that Inside initiates a truly affective and interactive mode of unhuman agency. As a congealed body of human and nonhuman actors, the unhuman is revealed both literally (via the subjectivity of ‘the huddle’) and subtly through the interrelations of player, narrative and gaming system. The game asks its players to ask questions, to be unknowing, and embrace a world that constantly toys with their ability to behold full agential grasp.

References

Anable, A. (2018). Playing with Feelings: Video Games and Affect. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Arnold, M. (2018). Inside the Loop: The Audio Functionality of Inside. The Computer Games Journal, 7(4), pp.203-211.

Ash, J. (2013). Technologies of Captivation: Videogames and the Attunement of Affect. Body & Society, 19(1), pp.27-51.

Bailey, A. (2018). Authority of the Worm: Examining Parasitism within Inside and Upstream Colour. Journal for Comparative Studies and Theory, 4(2), pp.35-53.

Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Boluk, S. LeMieux, P. (2017). Metagaming: Playing, Competing, Spectating, Cheating, Trading, Making, and Breaking Videogames. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Braidotti, R., Hlavajova, M. (2018). Posthuman Glossary. London: Bloomsbury.

Cottom, D. (2006). Unhuman Culture. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2014). Flow and the Foundation of Positive Psychology: The Collected Works of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. Dordrecht: Springer.

Diaz, R. (2018, June 16). The “Flow” state’s influence during game design process. Retrieved from https://medium.com/@raydaz/the-applications-relevance-of-flow-state-design-in-video-games-1572dac0d2c.

Foucault, M. (1975). Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. London: Penguin.

Gallagher, R. (2018) Videogames, Identity and Digital Subjectivity. New York: Routledge.

Galloway, A.R. Thacker, E. (2007). The Exploit: A Theory of Networks. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

GDC. (2018, January 29). Huddle up! Making the [SPOILER] of INSIDE. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gFkYjAKuUCE.

Hardt, M. Negri, A. (2005). Multitude: War and Democracy in the Age of Empire. London: Penguin.

Hayles. N. K. (1999). The Condition of Virtuality in The Digital Dialectic: New Essays on New Media. In P. Lunenfield (Ed.). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Krzywinska, T. (2002). Hands-On Horror. Spectator 22(2), pp.12-23.

Muriel, D., Crawford, G. (2018). Video Games and Agency in Contemporary Society, Games and Culture. pp.1-20.

Murray, J.H. (1997). Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Shinkle, E. (2005). Feel It, Don’t Think: the Significance of Affect in the Study of Digital Games. Proceedings of DiGRA 2005 Conference: Changing Views—Worlds in Play.

Trigg, D. (2014). The Thing: A Phenomenology of Horror. Winchester: Zero Books.

Tulloch, R. (2014). The Construction of Play: Rules, Restrictions, and the Repressive Hypothesis. Games and Culture, 9 (5), pp.335-350.

Whitehead, N., Wesche, M. (2012). Human No More: Digital Subjectivities, Unhuman Subjects, and the End of Anthropology. Boulder: University Press of Colorado.

Williams, V. (2018). Frameless Fictions: Exploring the Compatibility of Virtual Reality and the Horror Genre. Refractory: A Journal of Entertainment Media, 30. https://refractory-journal.com/30-Williams/.

Ludography

Inside, Playdead, Denmark, 2016.

Author’s Info

Vicki Williams

University of Birmingham

VRW203@student.bham.ac.uk

Endnotes

- See Mathew Arnold (2018). Inside the Loop: The Audio Functionality of Inside. The Computer Games Journal, 7 (4). pp.203-211. ▲

- See Vicki Williams (2018). ‘Frameless Fictions: Exploring the Compatibility of Virtual Reality and the Horror Genre’. Refractory: A Journal of Entertainment Media, 30. https://refractory-journal.com/30-Williams/. ▲

- Playdead were unable to provide an image of ‘The Huddle,’ it being the ‘secret’ hidden at the end of the game. To find out more about ‘The Huddle’ and how it was made, please watch the video from the Game Developers Conference (GDC, 2018) ‘Huddle up! Making the (SPOILER) of INSIDE.’ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gFkYjAKuUCE. ▲

- Rob Gallagher coins the phrase “beastly bodies” in his Videogames, Identity and Digital Subjectivity. Gallagher uses this as a framework for capturing the ways bodies are subject to “beastly drives, temptations, and losses of agency” (p.103) during gameplay. ▲

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.