Ilaria Mariani (Politecnico di Milano), Mariana Ciancia (Politecnico di Milano), Judith Ackermann (Potsdam University of Applied Sciences)

Abstract

This paper delves into Interactive Digital Narratives (IDNs) as powerful artefacts for challenging dominant narratives and promoting inclusive storytelling. The study is based on a literature review of the research discourse on IDNs, aiming to discern their potential to support and address counter-narratives. Triangulation and systematisation of the existing knowledge corpus, key themes, theoretical frameworks, and studies surrounding IDN and counter-narrative were conducted, collecting primary definitions and identifying for each domain relevant clusters. Five original scientific works by as many scholars that constitute this special issue are explored and mapped against this backdrop and associated with IDN and counter-narrative clusters. This process highlights their alignment with the research discourse, leading to the identification of intersections between IDNs and counter-narratives from diverse perspectives. This exploration sheds light on how IDNs can serve as counter-hegemonic narratives, being spaces for alternative perspectives and identities that challenge dominant ideologies. Ultimately, the requisite preconditions for IDNs to function as counter-narratives are discussed.

1. Introduction. IDNs as Counter-Hegemonic Narratives and Expression of Identity

Narrative is recognised as the most ancient way to communicate ideas (Bruner, 1991). Human beings organise experiences as narratives (Bruner, 1990), confirming them to be a tool for the construction of reality and supporting the constant negotiation of meanings (Bruner, 1990) The media and digital landscape, as exemplified by various digital configurations (Ackermann et al., 2020, p. 417), profoundly changed how individuals think, behave, live, and interact.

Fueled by the unceasing advancements in technology that have revolutionised the way narratives are created and consumed, offering vast possibilities and potentials with significant implications for expression both from the perspective of authors and players, the discourse on IDNs is today growingly prominent in scholarly debates (Koenitz, 2018; Koenitz et al., 2015).

The current state and possibilities of the media landscape in the field of interaction and participation rely on a logic that significantly differs from the past. On the one hand, it prompts a critical examination and revision of the contemporary role of the user, who is now empowered with growing agency. On the other hand, it requires a comprehensive understanding of how to effectively harness the opportunities presented by multimedia, and multichannel approaches such as crossmedia and transmedia (Ciancia, 2018). IDNs capitalise on the fundamental features of interactive media and platforms, including video games, virtual reality, web-based experiences, and transmedia systems, to immerse users in dynamic and participatory storytelling. Unlike traditional linear narratives, they allow users to shape the narrative through their choices, actions, and interactions, thereby blurring the boundaries between storyteller and audience. This shift in the storytelling paradigm has opened up new possibilities for creative expression, engaging users in a more active and personalised narrative experience. Moreover, this shift can foster and spread counternarratives that contradict the currently dominant one by presenting a different perspective on socially relevant topics. Therefore, IDNs rely on the established and recognised role of narratives in shaping our understanding and forming judgments while exploiting technological potentialities to favour interaction with the contents. These features empower IDNs as a means for sharing perspectives and experiences, enabling self-expression for all the different actors involved, while capitalising on engagement, immersion, and participation.

As such, IDNs emerge as a powerful means to promote inclusive narratives and create space for counternarratives to thrive. In light of such premises, IDN for social change arises as a significant subject at the centre of research and experimentation, grounded in various epistemologies and investigated by academics and practitioners from a variety of fields (Dubbelman et al., 2018; Lueg & Wolff Lundholt, 2020).

This paper aims at exploring IDNs as means for challenging the hegemonic narrative as a dominant perspective, leveraging interaction and participation as constitutive features to open up discussions able to go beyond entertainment. It investigates how offering varying degrees of interaction with the content can make them spaces to encourage exploration, discussion, and critical examination of relevant social issues on a cognitive level as well as addressing empathy and care on an emotional level. The process involves intertwining diverse elements. Firstly, a thorough analysis and systematisation of the research discourse on IDN will enable an understanding of its potential to support and address counter-narratives. Secondly, the presentation of five original scientific works on IDN, comprising this special issue, will examine their alignment with the research discourse and explore their contributions to comprehending the intersections of IDN and counter-narratives from varying perspectives. Lastly, IDNs potential as well as the accompanying preconditions to function as counter narratives will be discussed.

2. Theoretical background on IDNs

Although recognising an established debate, it is in recent years that IDNs gained further momentum leveraging technological advances that increase their potential to engage users in immersive and participatory storytelling experiences. As a result, they have been receiving increasing attention from scholars and practitioners. However, the current understanding of IDNs is rooted in a substantial body of prior scholarship. In order to shed light on the foundations of this field, it is important to examine the works of key authors and their contributions. By exploring their research, we can gain insights into the evolution and development of IDNs as a scholarly discipline.

2.1 Analysing IDNs in the literature

IDNs emerges as a dynamic and evolving form of storytelling that combines traditional narrative elements with interactive technology. Their interactive and feedback-driven nature make IDNs lean towards the notion of a narrative environment as a cybernetic system. Aarseth (1997) introduces the concept of ‘ergodic literature’ referring to works that require non-trivial effort from the user to traverse the text. Aarseth’s perspective on cybertext refers to a category of textuality that is intricately tied to the capabilities and interactive nature of digital media. A notion that emphasises the importance of user participation and engagement, including various forms of interactive storytelling, and IDNs among them. Moving in the game studies field, Aarseth developed theoretical frameworks and models to analyse the structure and agency of interactive storytelling. His work is based on narrative theory of games, and advances reflections on topics such as player agency, ludology, and the interplay between narrative and gameplay (Aarseth, 2012). While Aarseth does not provide a direct definition of IDN, his work serves as a significant contribution by offering valuable insights into the complexities of narratives within digital environments. In the same period, Murray (1997) articulates the reasoning on IDNs by introducing three fundamental concepts: (i) immersion, (ii) agency, and (iii) transformation, later recalled and further expanded by other seminal authors. Immersion refers to the sensation of being fully absorbed in an alternative reality, capturing one’s complete attention and engaging all senses. Achieving immersion requires not only suspending disbelief (Coleridge, 1817) but actively embracing belief. The discourse on immersion and interactivity are also addressed by Ryan (2001), examining how they shape narrative experiences. She also described how narrative adapts to different mediums and explores its relation to interactive media and virtual reality, also vetting the concept of ‘narrative avatar’ (2006a). Her analysis of cognitive processes and narrativity (Ryan, 2006b) provides insights into the cognitive and emotional dimensions of interactive storytelling. Looking at the exchange of meaning between authors and readers, her research delves into the communicative aspects (Grishakova & Ryan, 2011). While immersion focuses on the environment, agency empowers participants to take meaningful actions and choices (Crawford, 2004; Laurel, 1991) and observe the consequences of such interaction in the progression and outcome of the story within a responsive and coherent world (Murray, 2004).

Crawford (2004) specifically explores the concept of ‘emergent narratives’ as the dynamic evolution of the story is based on user input and the system’s responses, nurturing personalised and unique storytelling experiences. Transformation implies a technological perspective, referring to the transformative capabilities of computational environments which enable multidimensional presentation, rearrangement, spatial and temporal organisation of ‘kaleidoscopic narrative’ as media mosaics (Manovich, 2001), adapting McLuhan’s observation on communication media as mosaic rather than linear in structure (McLuhan, 1964). As such, Murray (1997) depicts IDNs as a means to construct narratives using predefined elements, such as the approach to narratology advanced by Russian formalists (Propp, 1968) and French structuralists (Genette, 1988; Greimas, 1983; Prince, 1982; Todorov, 1966, 1975), based on the identification of key elements, functions, and structures of narratives. Transformation relates to the immersive enactment within a cyberdrama, which can evoke catharsis and facilitate juxtapositions for reflective purposes.

In the attempt of moving from theory to practice, the most significant contribution to IDNs comes from the studies of Koenitz. His research ranges from the analysis of existing theoretical perspectives to foreground the scope and focus of previous contributions to drive further explorations in the domain (2015). This is the result of a consistent research on theoretical frameworks for interactive storytelling (Koenitz, 2010, 2023), bringing support for concrete implementations to practical design IDNs. Koenitz’s research also addresses the technical challenges and considerations in implementing IDN systems. He specifically sheds light on the construction and design principles of these immersive narrative experiences (Koenitz, 2015a, 2016). By analysing user behaviour, preferences, and interactions, and evaluating user experience, he seeks to understand the cognitive and affective aspects of user engagement in interactive narratives also, connecting entertainment theory with a humanities-based perspective (Roth & Koenitz, 2016). Finally, Koenitz has argued that IDNs have the potential to be used for more than entertainment, and that they can be used to engage users in a range of educational activities and prompt users to reflect on important social and political issues (Koenitz, Barbara, & Eladhari, 2022), identifying the potential of IDNs for education (Koenitz et al., 2019; Koenitz, Barbara, & Eladhari, 2022) and social change (Dubbelman et al., 2018).

The literature review reveals commonalities among the perspectives of key scholars who have contributed to the discourse on IDN and pushed it forwards. Firstly, they share a recognition of the transformative impact of digital technology on narrative forms and storytelling experiences, emphasising the interactive nature of IDNs that empowers users in the narrative construction process. This acknowledgment underscores the departure from traditional linear narratives towards dynamic, user-driven narratives. Secondly, these scholars underscore the significance of agency and user engagement within IDN. Interactivity is spotlighted as a pivotal element, enabling users to make choices, shape the narrative trajectory, and influence outcomes. The concept of agency aligns with the notion that users should possess a sense of control and influence over the narrative, leading to heightened immersion and meaningful engagement. Thirdly, the authors acknowledge the blurring boundaries between creators and participants in IDN. They explore the concept of co-creation and collaborative storytelling, where users assume the role of active contributors to the narrative, be it through content generation, interaction with the narrative system, or participation in communal storytelling. This paradigm shift challenges conventional notions of authorship and meaning creation, underscoring the democratisation of storytelling in the digital era. Pivotal is how IDNs allow users to actively participate and influence the narrative through their choices, actions, and interactions within the digital environment, making the narrative unfold depending on branching paths and user decisions, leading to multiple outcomes. As such, a key feature of IDN is the attempt to reach a (at least assumed) personalised and interactive storytelling experience, opening the debate known as the paradox of authored narratives. The paradox arises from the inherent tension between maintaining authorial control and accommodating player agency (Murray, 1997; Fernández-Vara, 2014). Authors strive to create a coherent and predetermined narrative structure, while the interactive nature of IDNs necessitates to provide players with the freedom to make choices that shape the story in a given frame. This paradox presents a challenge in achieving a harmonious balance between authorship and interactivity, where authors must navigate the delicate interplay of guiding the narrative trajectory while still providing meaningful player agency. Addressing this paradox is crucial for designing IDNs that offer both a structured narrative experience and engaging interactive elements, thereby enhancing immersion and user engagement.

Despite these commonalities, variations emerge in the perspectives of the authors, stemming from differences in theoretical frameworks, disciplinary backgrounds, and research foci. The literature review confirms how the research on IDNs appears to be twofold. The humanities-based research described so far, which focused the attention on the user experience that IDNs generate, analysing their creative potential against the traditional forms of narrative. On the other hand, computer science-based IDN research has privileged a technological perspective, confirmed by the large attention on developing advanced computational systems able to generate highly responsive and generative experiences (Kim & Kim, 2016; Van Velsen, 2008; Ventura & Brogan, 2003), and authoring tools supporting IDN generation (Green et al., 2021; Kim & Kim, 2016; Koenitz, Barbara, & Bakk, 2022; Moallem & Raffe, 2020; Sylla & Gil, 2020). A complementary perspective comes from studies which zeroed in computational models of narrative (Szilas, 2021; Young & Riedl, 2003; El-Nasr, 2004), emphasising the role of AI driven interactive narrative systems in accounting for player actions. In this sense, the literature highlights lunges on system affordances for emergence and authorial control, mapping the levels of interaction provided by different interactive narrative systems along a spectrum of agency architectures (Moallem & Raffe, 2020). Multiple studies explore the wide spectrum of technologies applied in the pursuit of creating better interactive narrative system, arraying from procedural plot generation subsystems (Szilas, 2021; Szilas & Richle, 2013; Thue et al., 2021) believable agents (Aha & Coman, 2017; Luo et al., 2015; McCoy et al., 2011; Riedl & Bulitko, 2012; Ware et al., 2022), natural language processing (NLP) (Ammanabrolu & Riedl, 2021; Mateas & Stern, 2003), and procedural content generation (Ammanabrolu, Broniec, et al., 2020; Ammanabrolu, Cheung, et al., 2020; Freiknecht & Effelsberg, 2020; Kreminski & Wardrip-Fruin, 2019).

The systematic analysis of their works provides a comprehensive understanding of the current state of IDN research and shed light on the evolving landscape of interactive storytelling. The commonalities highlight shared interests and directions while divergences offer a diverse and multifaceted understanding of IDN, underscoring the various lenses through which researchers approach and contribute to the field.

2.2 From IDNs definitions to IDN clusters

The concept of IDN was introduced to narrow down and push forward the discussion on a domain that up to that moment was still blurred as referred to by adopting terms borrowed from neighbouring fields. Till then, using one term or the other specifically emphasised and connected the discourse to the scientific perspective and domain through which the argument was observed: Computer Science, Narrative Theory, Game Studies, and Media Studies. Currently, IDN emerges as an umbrella term that describes work in the areas of intelligent narrative technologies, interactive narrative, interactive drama, interactive fiction, interactive storytelling, and narrative games (Crawford, 2004; Montfort, 2015, p. x).

The introduction of the IDN concept in 2015 by Koenitz (2015a, 2015b) allowed a step forward, serving as a standard term that helped to productively broaden concepts established by previous terms that became perceived to be excessively restricted. Despite a relevant academic literature dedicated to exploring and developing the field, a systematisation of knowledge across multiple domains is still lacking, evident in the absence of systematic literature reviews examining data and findings from the multiple authors who are contributing to the definition of the concept, its fundamentals, its features, and so on.

Although multiple authors are contributing to the field, a scoping of the most relevant contributions on IDNs over the last decades highlights a prominence of few authors. Table 1 reports the dominant definitions provided in the academic literature.

Table 1: Dominant IDNs definitions in the academic literature.

|

ID |

Definition |

Reference |

|

IDN01 |

Interactive narrative is a form of digital interactive experience in which users create or influence a dramatic storyline through actions, either by assuming the role of a character in a fictional virtual world, issuing commands to computer-controlled characters, or directly manipulating the fictional world state. It is most often considered as a form of interactive entertainment but can also be used for serious applications such as education and training. |

Riedl & Bulitko, 2012, p. 68 |

|

IDN02 |

Interactive digital storytelling (IDS) aims at generating dramatically compelling stories based on the user’s input. |

Smed, 2014, p. 22 |

|

IDN03 |

Interactive Digital Narrative (IDN) connects artistic vision with technology. At its core is the age-old dream to make the fourth wall permeable; to enter the narrative, to participate and experience what will unfold. IDN promises to dissolve the division between active creator and passive audience and herald the advent of a new triadic relationship between creator, dynamic narrative artefact and audience-turned-participant. Within this broad vision of fully interactive narrative environments through the use of digital technologies, IDN aggregates different artistic and research directions from malleable, screen-based textual representations to the quest for virtual spaces in which human interactors experience coherent narratives side by side with authored narrative elements and synthetic characters. |

Koenitz et al., 2015, p. 1 |

|

IDN04 |

IDN as a novel form of expression in which narrative and interactivity are deeply intertwined, as “system narratives” in line with Roy Ascott’s call for reactive “system art” in contrast to prior “object art.” |

Koenitz, 2015a, p. 52 |

|

IDN05 |

Interactive digital narrative (IDN) challenges basic assumptions about narrative in the western world—namely about the role of the author and the mixed state of content and structure as the audience takes on an active role and the narratives become malleable. […] IDN can now be characterised as a form of expression enabled and defined by digital media that tightly integrates interactivity and narrative as a flexible cognitive frame. |

Koenitz, 2015b, p. 91 & 92 |

|

IDN06 |

[…] IDN can now be defined as an expressive narrative form in digital media implemented as a computational system containing potential narratives and experienced through a participatory process that results in products representing instantiated narratives. |

Koenitz, 2015b, p. 98 |

|

IDN07 |

Interactive Digital Narrative is an expressive form in the digital medium, implemented as a computational system containing a protostory of potential narratives that is experienced through a process in which participants influence the continuation of the unfolding experience that results in products representing instantiated stories. |

Koenitz et al., 2018, p. 108 |

|

IDN08 |

Interactive digital narrative is a narrative expression in various forms, implemented as a multimodal computational system with optional analog elements and experienced through a participatory process in which interactors have a non-trivial influence on progress, perspective, content, and/or outcome. |

Koenitz, 2023, p. 5 |

The collected definitions show how the concept opens up from a mostly tech-view to an interdisciplinary space that intersects the two streams of Computer Science, and Arts and Humanities. Table 1 captures the fragmented, distributed and interactive nature of an IDN, showing how the majority of available definitions features a variety of foci, ranging from technical features to scope and fields of application, bringing together the technical aspects of the first with the creative and theoretical aspects of the latter.

On the one hand, in the context of IDNs, Computer Science plays a crucial role in providing the technical foundation and computational infrastructure, comprising areas such as human-computer interaction, artificial intelligence, and software engineering. Computer Science contributes to the development of interactive systems, algorithms, and technologies that enable user interaction within digital narratives. It involves designing user interfaces, implementing interactive features, and leveraging computational techniques for narrative generation and adaptation. Additionally, Computer Science methods are utilised for data processing, user modelling, and evaluating user experiences within such narratives. On the other hand, IDNs draw upon the artistic and theoretical aspects of Arts and Humanities disciplines. They incorporate narrative theory, storytelling techniques, and cultural studies to create engaging and meaningful interactive experiences. Arts and Humanities contribute narrative expertise and critical analysis through the exploration of themes, characters, plot structures, and the socio-cultural implications of interactive narratives. They provide frameworks for analysing narrative elements, character development, and the impact of IDNs on audience reception and interpretation. Additionally, Arts and Humanities disciplines bring critical perspectives, ethical considerations, and cultural context to the design and evaluation of IDNs.

The interdisciplinary nature of IDNs lies in the fusion of Computer Science and Arts and Humanities. It involves collaboration between technologists, artists, and researchers from various fields. Computer Science contributes technical expertise to implement interactive features and computational frameworks, while Arts and Humanities bring narrative expertise and critical analysis necessary for effective storytelling and user engagement. This integration enables IDNs to explore innovative narrative forms, enhance user experiences, and examine the broader cultural and societal implications of interactive storytelling. By combining the computational capabilities of Computer Science with the creative and theoretical insights of Arts and Humanities, IDNs aspire to craft immersive, interactive, and culturally meaningful narrative experiences that deeply resonate with audiences while leveraging the potential of digital technologies.

By considering the bulk of definitions, a pivotal aspect pertains to how the introduction of IDN as a common term has clarified the conceptual ambiguity that existed in previous definitions. Specifically, it has addressed the confusion between the notions of IDNs, interactive drama (Laurel, 1991; Murray, 1997) or interactive fiction (Aarseth, 1997; Montfort, 2011), and the broader concept of interactive storytelling. While interactive drama and interactive fiction can be viewed as typologies of IDN with a focus on the narrative genre, they should be distinguished from interactive storytelling (Crawford, 2004), which comprehensively includes multiple forms of storytelling that provides the users with the ability to interact and shape the narrative to varying degrees. It can include both digital and non-digital media, such as live performances, choose-your-own-adventure books, role-playing games, live action role-playing games (LARP), improvisational theatre, and even the narrative resulting from the interaction with conversational agents. Although both engage the user by design, empowering it to contribute to the narrative by making choices, providing input, and participating in the story’s unfolding, IDNs specifically refer to experiences occurring within digital or virtual environments as to be seen in IDN01, IDN03, IDN05, IDN07, IDN08. On the other hand, interactive storytelling concerns a broader set of participatory narratives, including digital and non-digital media.

The definitions presented in Table 1 are organised into thematic clusters based on the analysis of their content. As such, Table 2 does not seek to offer a comprehensive analysis of the topics addressed in the discourse on IDN, but rather identifies and highlights the emerging thematic clusters that have emerged from the set of definitions analysed.

Table 2: Thematic clusters from IDNs definition

| Thematic clusters | IDNs and definition highlights | |

| 1 | IDN as a Form of Dramatic Experience |

|

| 2 | IDN as a Fusion of Artistic Vision and Technology |

|

| 3 | IDN as an Expressive Narrative Form in Digital Media |

|

Cluster 1 looks at IDN as a captivating experience that seeks to generate dramatic stories by incorporating user input. This cluster is based on Laurel’s (1991) definition of dramatic stories as opposed to narrative stories by the following properties: they favour enactment over description, intensification over extensification, and unity of action over episodic structure. As illustrated by Smed (2014, p. 22 – IDN02), IDN seeks to create narratives that captivate users through their active involvement. Riedl and Bulitko (2012, p. 68 – IDN01) emphasise the foundational role of users who assume character roles, issue commands, or manipulate virtual worlds to shape dramatic storylines. Their definition also highlights the multifaceted nature of IDN and its applications across domains such as entertainment, education, and training, where the interactive engagement of users enhances the overall narrative experience.

Cluster 2 portrays IDNs as the harmonious fusion of artistic vision and technology, facilitating the convergence of creative expression and narrative interactivity. Koenitz and colleagues (Koenitz et al., 2015, p. 1 – IDN03) clarify the overarching goal of IDN in blurring the traditional boundaries between authors, narrative artefacts, and the audience-turned-participants. By combining artistic works with technological advancements, IDN embraces diverse artistic and research directions. From screen-based textual representations to virtual spaces hosting coherent narratives and synthetic characters, IDN pioneers the creation of immersive and dynamic narrative environments as ‘system narratives’ (Koenitz, 2015a, p. 52 – IDN04).

Cluster 3 intends IDN as an expressive narrative form in digital media that regards a transformative narrative paradigm, challenging established assumptions and harnessing the potential of digital media. Koenitz (2015b, p. 98 – IDN06) defines IDNs as an expressive narrative form that unfolds within digital media, implemented as computational systems housing potential narratives. He delves into the disruption caused by IDN, wherein audience engagement and the malleability of narratives stand as central tenets (2015b, pp. 91–92 – IDN05). Additionally, Koenitz further underscores the expressive nature of IDN (Koenitz, 2018, p. 108 – IDN07), highlighting how participants actively influence the unfolding experience and contribute to the instantiation of stories, broadening the scope of IDNs in 2023 (Koenitz, 2023, p. 5 – IDN08): a diverse narrative expression, realised through multimodal computational systems that afford significant interactor influence.

In this discourse, transversal to the three clusters, a prominent role is played by procedural rhetoric (Bogost, 2007), highlighting how the interactive systems within IDNs convey meaning and shape the narrative, leading to examine the rhetorical power of interactive elements, such as choices, branching narratives, and feedback mechanisms, in shaping user engagement and interpretation. Procedural rhetoric is a concept coined by Bogost (Bogost, 2007, 2021; Anderson et al., 2019), which refers to the persuasive ability of interactive systems to leverage their rules and mechanics to convey meanings. The concept of procedural rhetoric is originally founded on the premise that games and simulations can mirror the structure of the real world. The inherent parallelism between games and reality provides games with the distinctive ability of representing not only how things are, but also advocating for how they ought to be, enabling players to make arguments on desirable or undesirable behaviours within the depicted world. Such an approach to argumentation diverges from more traditional forms of rhetoric – such as verbal or visual modes – prompting the new classification of procedural rhetoric. IDNs, as interactive systems, rely on the interplay of various mechanics to convey meanings and engage players. Against this backdrop, IDNs that employ counter-narratives can exploit procedural rhetoric to communicate the underlying themes and perspectives of the topic addressed in a persuasive manner, shaping players’ experiences and evoking specific understandings. Specifically, procedural rhetoric can be harnessed to reinforce and amplify the intended messages and ideologies embedded in the narrative. Through a wise design of interactive choices and eventual gameplay elements, IDNs can support the exploration of alternative perspectives within the narrative context, shaping player experiences, fostering empathy, and prompting critical reflection on social, cultural, or political issues. For instance, the design choices of an IDN can simulate a mediated experience on the challenges and obstacles faced by marginalised individuals or present alternative scenarios that challenge the status quo. By immersing players in these experiences and engaging them in interactive decision-making, IDNs can challenge preconceived notions and engage players actively in the exploration and construction of meaning.

3. Theoretical background on Counter-Narratives

Since the need for action demands alternative narrative forms that tackle social issues, creating more engaging but equally informative messages, we can promote the IDNs as artefacts capable of articulating existing discourses by bringing out alternative strands to dominant thoughts within meaning-making and the process of negotiating meaning.

In the last decade, there has been a notable increase in the emergence of IDNs that welcome manifestation and actively foster discourse on urgent or contentious topics, adopting alternative perspectives that deviate from the dominant narrative, in some cases even challenging it. Within this context, IDNs have encountered the concepts of counter-narrative and counter-storytelling, which extend beyond the mere retelling of marginalised individuals’ stories to advocate for their viewpoints in a space that allows interaction at multiple levels. IDNs have become a powerful means for marginalised groups to convey their narratives, a practice that has significantly evolved over the past two decades. This evolution can be attributed to the development and enhancement of open access and user-friendly tools, which empower marginalised communities to express themselves by creating their own interactive stories. Twine (https://twinery.org), an open-source program for web-based interactive fiction, exemplifies this trend. By simply enclosing words and sentences within squared brackets, it allows the generation of branching stories, offering and exploring remarkable flexibility akin to the web itself. Since its inception in 2009, Twine has revolutionised the landscape of interactive art, digital narratives, and games (Harvey, 2014). It gave rise to a new form of expression characterised by an unconventional and poetic nature, distinct from the commercial mainstream. Its versatility, akin to that of the web itself, has enabled the emergence of new forms of games: queer, small, and poetic, which depart from conventional gaming. In this field, beyond mere creation of games, Twine has provided a voice to those who were left at the margins, and ensured an avenue of expression for groups historically alienated from the industry (Heron et al., 2014; Todd, 2015; Janine et al., 2007), paving the way for the formation of a vibrant and fresh queer and woman-orientated game-making community. At broad, what Twine and its user-friendly, intuitive interface did is allow non-programmers to develop IDNs with ease, outputting interactive stories as simple HTML pages with branching narratives.

As a result, Twine and a bunch of more recent although less established software have been empowering all aspiring IDN creators, regardless of coding expertise, ushering in a wealth of possibilities that promote inclusivity and diversity within the realm of IDN development.

In such a landscape, by incorporating counter-narrative, IDNs serve the purpose of representing and amplifying the voices and perspectives that are often overlooked or excluded from the dominant discourse. With their interactive and immersive nature, IDNs offer a unique space for such experiences and perspectives to be acknowledged and understood while exploiting affordances specific to the media to foster a more comprehensive understanding. They potentially engage players in diverse, transformative and thought-provoking narrative experiences that explore social issues, question existing paradigms, and promote inclusivity, thus leveraging interactivity for encouraging critical thinking, self-reflection, and participation. In light of this premise, in order to advance in this discourse and vet the interplay between IDNs and counter-narrative it becomes necessary to delve into the articulation of current definitions of counter-narrative and identify their foundational features. This exploration is essential to comprehending the potential role of IDNs in facilitating self-reflection processes and encouraging (in the long run) a more active engagement within a more inclusive, plural, and socially aware society.

3.1 Defining Counter-Narrative

The analysis of the concepts in the literature depicts counter-narratives highly multidisciplinary, including heterogeneous viewpoints that bring together the leading perspectives of seminal academics and practitioners as shown in Table 3.

Table 3: Dominant counter-narrative definitions in the academic literature.

|

ID |

Definition |

Reference |

| CN01 | […] the idea of counter-storytelling and the inclusion of narratives as a mode of inquiry offer a methodology grounded in the particulars of the social realities and lived experiences […] | Matsuda, 1993, p. 212 |

| CN02 | [Counter-narratives as] naming one’s own reality” or “voice” by critical race theorists through “parables, chronicles, stories, counterstories, poetry, fiction and revisionist histories to illustrate the false necessity and irony of much of current civil rights doctrine | Ladson-Billings & Tate, 1995, p. 56 |

| CN03 | [Counter-story as] counter-reality that is experienced by subordinate groups, as opposed to those experiences of those in power | Delgado & Stefancic, 1995, p. 194 |

| CN04 | We believe counter-stories serve at least four functions as follows: (a) They can build community among those at the margins of society by putting a human and familiar face to educational theory and practice, (b) they can challenge the perceived wisdom of those at society’s center by providing a context to understand and transform established belief systems, (c) they can open new windows into the reality of those at the margins of society by showing possibilities beyond the ones they live and demonstrating that they are not alone in their position, and (d) they can teach others that by combining elements from both the story and the current reality, one can construct another world that is richer than either the story or the reality alone. | Solórzano & Yosso, 2002, p. 36 |

| CN05 | counter-storytelling is a means of exposing and critiquing normalized dialogues that perpetuate racial stereotypes | DeCuir & Dixson, 2004, p. 27 |

| CN06 | Counter narratives only make sense in relation to something else, that which they are countering.The very name identifies it as a positional category, in tension with another category. The very name identifies it as a positional category, in tension with another category. But what is dominant and what is resistant are not, of course, static questions, but rather are forever shifting placements. | Bamberg & Andrews, 2004, p. x |

| CN07 | The stories which people tell and live which offer resistance, either implicitly or explicitly, to dominant cultural narratives. […] Counter-narratives exist in relation to master narratives, but they are not necessarily dichotomous entities. | Andrews, 2004, p. 1-2 |

| CN08 | Perspectives that run opposite or counter to the presumed order and control are counter narratives. These narratives, which do not agree with and are critical of the master narrative, often arise out of individual or group experiences that do not fit the mas- ter narratives. Counter narratives act to deconstruct the master narratives, and they offer alternatives to the dominant discourse in educational research. They provide, for example, multiple and conflicting models of understanding social and cultural identities. | Stanley, 2007, p. 14 |

| CN09 | Counter-narrative refers to the narratives that arise from the vantage point of those who have been historically marginalized. […] the effect of a counter-narrative is to empower and give agency to those communities. By choosing their own words and telling their own stories, members of marginalized communities provide alternative points of view, helping to create complex narratives truly presenting their realities. | Mora, 2014, p. 1 |

| CN10 | The concept of counter- narratives covers resistance and opposition as told and framed by individuals and social groups. Counter- narratives are stories impacting on social settings that stand opposed to (perceived) dominant and powerful master-narratives. | Lueg & Lundholt, 2020, p. iii |

| CN11 | Counter-narratives are able to achieve educational equity by giving voices to silenced and marginalized populations aimed at informing and educating dominant and elite groups, geared toward the ultimate goal of revealing the truth that “our society is deeply structured by racism” (Delgado, 1990, p. 98). | Miller et al., 2020, p. 273 |

| CN12 | Most affirmatively, counter-narratives can be interpreted as creative, innovative forces fostering beneficial societal change; forces holding productive potential for progress, development, as well as for ethical issues such as justice and accessible resources. | Lueg et al., 2020, p. 4 |

| CN13 | Counter-narratives are critical reinterpretations of dominant narrative models; they typically question the power structures underlying master- narratives and shed problematizing light on them. At the same time, however, it is important to acknowledge that individuals are largely unaware of the power structures they perpetuate through their narrative interpretations. Power dynamics play an important role in shaping not just the narrative webs in which we are entangled but also us as subjects who exercise our narrative agency by following and (re)interpreting culturally available narrative models. Power not only structures the options we have in constructing our life stories but also shapes the subject who chooses between and negotiates various narratives (see Allen, 2008, p. 165). Even when we engage in telling counter-narratives, we are not outside realms of power. | Meretoja, 2020, p. 34 |

When grouping these definitions according to their thematic perspectives, three main thematic clusters addressing counter-narratives evolve as follows: i) narrative inquire, ii) resistance and opposition to the hegemonic telling, and iii) lever to foster empowerment and agency (Table 4).

Table 4: Thematic clusters from counter-narrative definitions

| Thematic clusters | Counter-narratives and definition highlights | |

| 1 | Counter-narratives as Narrative Inquiries |

|

| 2 | Counter-narratives as Resistance and Opposition |

|

| 3 | Empowerment and Agency through Counter-narratives |

|

Cluster 1 points out how counter-storytelling and the inclusion of narratives offer a profound means of inquiry that goes beyond traditional approaches. According to Matsuda (1993, p. 212 – CN01), counter-narratives centre around narrative inquiries, emphasising the methodology rooted in social realities and lived experiences. These counter-narratives inherently challenge hegemonic stories and the bundle of presuppositions, perceived wisdom, and shared cultural understandings that individuals from dominant races bring to discussions on race. Solórzano and Yosso (2002, p. 36 – CN04) emphasise the multifaceted functions served by these counter-stories, including community building among marginalised groups, the disruption of established belief systems, the revelation of possibilities beyond marginalised experiences, and the demonstration of the transformative potential that arises from combining elements of both the story and current reality.

Cluster 2 focuses on counter-narratives as acts of resistance and opposition to dominant cultural narratives. Counter-narratives within this cluster involve ‘naming one’s own reality’ and asserting one’s voice, as critical race theorists Ladson-Billings and Tate (1995, p. 56 – CN02) emphasised. These narratives can take various forms, such as parables, chronicles, stories, counterstories, poetry, fiction, and revisionist histories, to illustrate the false necessity and irony inherent in prevailing civil rights doctrines, exposing and critiquing normalised dialogues that perpetuate racial stereotypes (DeCuir & Dixson, 2004, p. 27 – CN05). As a matter of fact, counter-narratives are situated in relation to master narratives (Andrews, 2004, pp. 1–2 – CN07) and challenge existing power dynamics, offering resistance to dominant cultural narratives and shedding light on the ever-shifting placements of dominance and resistance (Andrews, 2004, p. x – CN06). In this sense, counter-narratives can be understood as alternative realities experienced by subordinate groups, contrasting with the perspectives and experiences of those in positions of power (Delgado, 1995, p. 194 – CN03), impacting social settings (Lueg & Wolff Lundholt, 2020, p. iii – CN10).

Within Cluster 3, counter-narratives focus on empowerment and agency, particularly for historically marginalised communities. These narratives arise from individual or group experiences and present alternative perspectives that counter the presumed order and control established by the dominant master narrative, offering different models for comprehending social and cultural identities (Stanley, 2007, p. 14 – CN08). Marginalised communities reclaim their agency and empower themselves by choosing their own words and telling their stories (Mora, 2014, p. 1 – CN09). These narratives facilitate the creation of complex narratives that authentically present the realities of marginalised groups, giving voice to silenced populations and informing and educating dominant and elite groups (Miller et al., 2020, p. 273 – CN11). Moreover, counter-narratives are seen as creative and innovative forces that have the potential to foster beneficial societal change, addressing issues of justice and equitable access to resources (Lueg et al., 2020, p. 4 – CN12). However, it is essential to recognize that power dynamics shape not only the narrative options available to individuals but also influence how counter-narratives are interpreted and their impact on societal power structures (Meretoja, 2020, p. 34 – CN13).

4. Methodology

The eleventh issue of G|A|M|E is situated at a crowded crossroads of Game Studies, Human-Computer Interaction, Interactive Digital Narratives, Digital Storytelling, Transmedia Storytelling, Design, Media Studies, Sociology and Anthropology. Valuing the highly interdisciplinary nature of the topic, we aim at contributions addressing IDNs as counter-hegemonic narratives from different and even cross-sector scientific perspectives. In order to do that, we conducted a literature review on IDNs and counter-narratives to collect the main definitions to identify topics and the relevant clusters covered. Specifically, this contribution triangulates and systematises the existing corpus of knowledge to understand what is meant for IDN and counter-narrative, their key themes, theoretical frameworks, and empirical studies surrounding them, highlighting the main thematic perspectives that emerged. Then, the essays written by 5 scholars were mapped against such knowledge to identify and discuss which aspects are covered and which are not. The selected papers and the order of their presentation should allow the readers to understand better how IDNs can serve as counter-hegemonic narratives and expressions of identity by challenging dominant ideologies and providing a platform for alternative narratives and identities.

5. Results

Building upon the theoretical background presented so far, IDNs can be designed to challenge the dominant discourse. They have the potential to disrupt and subvert dominant narratives by offering alternative perspectives and narratives that challenge prevailing ideologies. They provide a space where marginalised communities and individuals can share their stories, experiences, and perspectives that often go unheard or misrepresented in mainstream media. Still, it needs to be said that this is not an automatism and that the personal connection between an author of an IDN and its topic seems to be very crucial for the perspectives presented and the meaningful choices allowed.

Given this framework, the papers of this special issue discuss IDN from different perspectives, all addressing in which ways IDNs relate to counter-narrative, and resulting in an overview of how the two domains encounter. Among the topics communicated, the ones of queerness as well as questions of gender identity and connected heteronomous perspectives towards people’s behavioural options occur most frequently. In creating IDNs, the designers apply different strategies in order to employ the features and affordances of the art form and to make sure that the player/user experiences the intended idea. Poirier-Poulin’s article shows by the example of A Summer’s End how trust and creating a feeling of intimacy towards the character of the IDN forms a strong bond between the player/user and the narrative, resulting in the wish and need to care for them. This can be enhanced by breaking the fourth wall, which is done in that example by sharing the inner monologue of the character, but can also be less subtle, as seen in She-Hulk: Attorney at Law discussed by Barbara and Haahr. Here the character directly speaks to the player/user asking them for another turn in the story. As an add on to the strategies already discussed, Barbara and Haahr elaborate on how presenting a character’s narrative as independent alongside the perspectives of designers and player/users can allow the latter to wish for the best ending for the characters, even though this might be distanced from their own desires or worldviews. For this it is important that the character enters into a complicity with the player, which can be created by breaking the fourth wall, for example. Similar ways of interweaving characters and players are discussed by Taylor-Giles and Turner, who emphasise the necessity of creating a notion of ‘co-desire’ between the both, to sync motives and actions. Taylor-Giles and Turner illustrate this by the example of generating a shared ‘vulnerability’ to be achieved when the player’s sense of emplacement and desire mirrors that of her on-screen representation. The authors argue that this can be supported by intensive character descriptions. In addition Ross Dionne, Sacy, and Therrien show how IDN can function as a safe environment for player/users to explore new identities – also or especially when placed in toxic environments or otherwise unbalanced relationships.

Euteneuer therefore moves away from looking at concrete IDN and their specifics to the idea of empowering people to design IDNs themselves. This can be seen as an important way in order to diversify designers’ communication aims and enable marginalised groups to allow others to experience their perspectives.

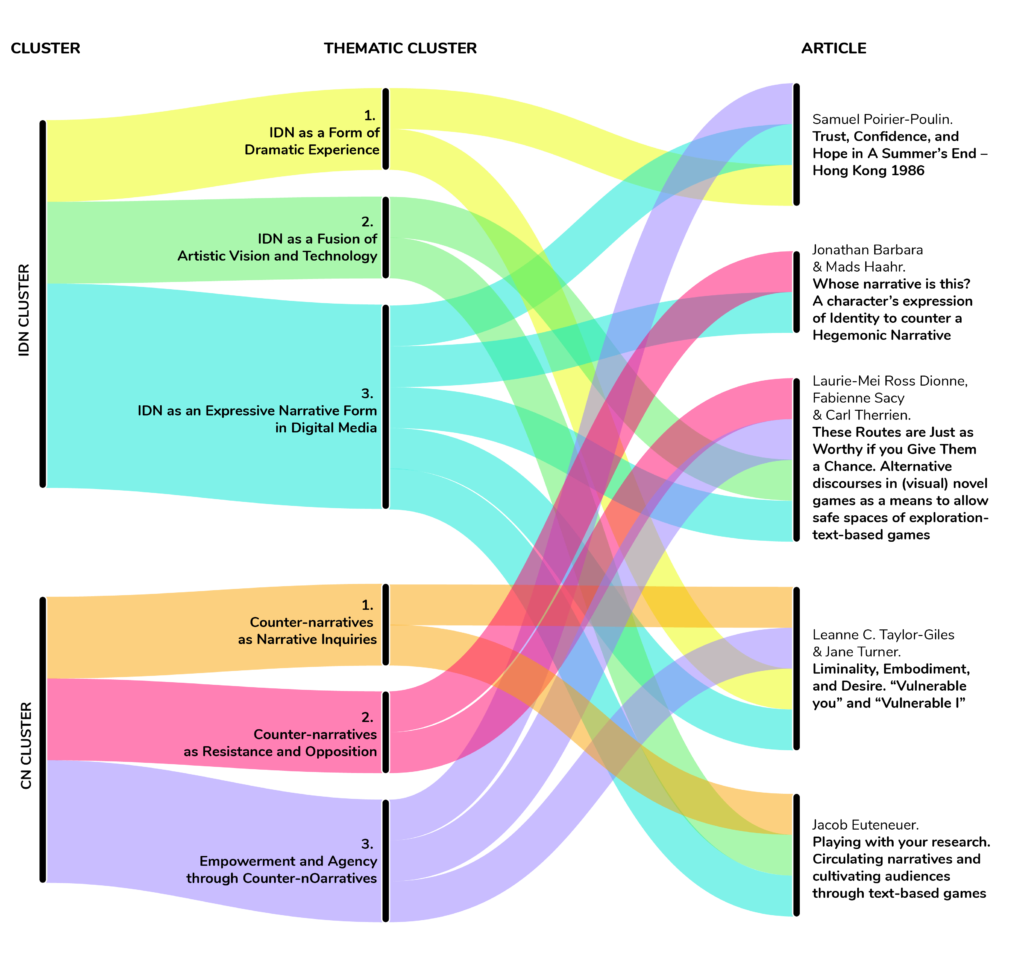

Moving from the perspective of the designers who created the IDNs to the way in which these have been addressed and discussed in the papers of this special issue, Figure 1 depicts how each contribution is related to the clusters of IDNs and counter-narratives outlined in Table 2 and Table 4 respectively. The associations depicted are established based on a thorough analysis of the articles included in the special issue. By examining the core themes and concepts explored in each contribution, we identified the ways in which the articles addressed different clusters related to IDNs and counter-narratives. Through this analysis, we determined the main points of convergence and divergence among the articles, shedding light on how each discusses IDNs and counter-narratives.

Figure 1: IDN and counter-narrative clusters associated with the curated articles of the special issue (download image).

Upon close examination of the contributions and their interrelation with the IDNs thematic clusters, it becomes evident that all authors concur in perceiving and exploring IDN as an Expressive Narrative form in Digital Media. Only partially, the contributions are focussing on IDN as a dramatic experience and IDN as a fusion of artistic vision and technology remains somewhat partial in comparison.

IDN Cluster 1 focuses on ‘IDN as a Form of Dramatic Experience’, exploring the captivating nature of interactive narratives that aim to generate dramatic stories through user input. The articles by Poirier-Poulin, and Taylor-Giles and Turner align with this cluster. The first delves into the theme of trust and its variations in the visual novel, showcasing how trust unfolds between game characters, players, and the video game medium. IDNs are recognised to foster intimacy and emotional connections between players and game characters. Moreover, they can provide positive and empowering queer representations. Through the unfolding of the narrative, trust is built between the player and the characters. Trust allows players to empathise with the characters and feel empowered as they accompany them on their journey. The author identifies a reparative reading approach as a prompt for seeking healing, reparation, and transformative understanding, exploring the impact on queer players and the potential to evoke hope and optimism. Likewise, Taylor-Giles and Turner’s article reinforces the dramatic experience in IDNs. The article explores how vulnerability is achieved between players and their on-screen representations, emphasising the importance of embodiment in enhancing the narrative identity. The idea of desire is used to classify an active player who subverts her own goals to mesh with those expressed by the character she controls. The idea of desire is used to classify an active player who subverts her own goals to mesh with those expressed by the character she controls. The concept of liminality, as an in-between state, is presented as a dynamic engine that maintains tension and vulnerability within immersive gaming experiences. Liminality is experienced by players who are fully immersed in the game world through sympathetic resonance with the player character, where shared desires or goals between player and character cultivate this resonance. The study highlights the importance of embodiment in narrative and character-oriented terms, rather than purely as a gameplay-centric concept. By discussing methods for increasing player-character co-desire and generating empathy, the article exemplifies how IDNs offer a deeply immersive and dramatic experience for users.

IDN Cluster 2 pertains to ‘IDN as a Fusion of Artistic Vision and Technology’, representing the harmonious merging of creative expression and narrative interactivity. Two articles bolster this cluster: one authored by Euteneuer and the other by Ross Dionne, Sacy and Therrien. Euteneuer’s article discusses how IDNs, created by academic researchers using Twine software, combine artistic works with technological advancements to disseminate important messages and engage audiences. The fusion of creative expression and text-based interactivity facilitates the spread of research findings in persuasive and innovative ways. Leveraging on affordances such as choice-driven narrative and their agency, IDNs engage users in active participation with the research content. As such, they are seen as a way to bridge the gap between academia and the public, able to make research more accessible and understandable for wider audiences while making it actionable for practitioners and stakeholders. Similarly, Ross Dionne, Sacy and Therrien’s article emphasises how visual novel games serve as a conduit for exploring diverse identities and sociocultural themes that are often underrepresented in mainstream media. By adapting specific templates and creating alternative discourses, IDNs in visual novels merge artistic vision with interactive narratives, enabling creators to explore new creative directions.

IDN Cluster 3 explores ‘IDN as an Expressive Narrative Form in Digital Media’, challenging established assumptions and harnessing the potential of digital media. Often bringing complementary perspectives, all the articles contribute to this cluster. Barbara and Haahr’s article explores how IDNs offer a transformative narrative paradigm by enabling characters to challenge hegemonic narratives. They stress how balancing character narratives with player narratives can facilitate identification (Cohen, 2001; Shaw, 2010), and writing character narratives that challenge stereotypes. From a formal standpoint, they highlight the level of control IDNs give over the narrative and the plot of the story, emphasising the importance of providing agency to the users in shaping the narrative as a plot rather than just the narrative discourse. On the content side, this embodies the expressive nature of IDNs, where character-driven agency provides a platform for inclusive storytelling. Ross Dionne, Sacy, and Therrien’s article highlights how novel games use branching narratives and alternate timelines to position themselves in the corpus of IDNs, offering players opportunities to relate to their avatars and explore various identities, contributing to meaningful individual stories. In line with this, Poirier-Poulin’s work explores the concept of multiperspectivity, emphasising the importance of trust and the relevance of including meaningful choices. The author discusses the narrative device of the inner monologue as an intimate dinnnnalogue with players, enhancing their connection with the characters and rendering them active participants in the storyworld. Moreover, IDNs are seen as a sort of ‘intimacy simulator’ that fosters a supportive relationship of care between players and characters. Through this intimate connection, players can accompany the characters through their journey, becoming supportive intermediaries, and nurturing a relationship of care with them. In doing so, they can gain a deeper understanding of queer experiences and perspectives, fostering empathy and familiarity with the queer topic. However, this expressive capacity of IDNs is seen as impacted by technological mediation. Taylor-Giles and Turner’s article advocates for a re-emplacement of liminality through (dis)embodiment, aligning player and character desires and strengthening the player’s sense of presence in the game world. From a complementary perspective, Euteneuer’s article introduces a complementary perspective on the expressive capacity of IDNs. Namely, their possible use to remix and transform academic research into engaging narratives, exploiting Twine. His contribution specifically points out how by broadening the scope of IDNs through multimodal computational systems that concern diverse and interactive narrative expressions, allowing an active participation of the audience, creators could reorient their research for a more engaging experience that puts the audience at the centre.

With regard to the integration of counter-narratives the most prominent feature of IDNs is recognised in creating empowerment and agency through narratives that challenge the dominant discourse. Compared to that, counter-narratives as narrative inquiries as well as as resistance and opposition play a less crucial role (see Figure 1). This gives the impression that IDN predominantly is employed as an expressive form of media art crafted to empower marginalised individuals by allowing others to understand their perspectives towards the world by creating meaningful connections and building bonds between player/users and characters. In order for this to work, a deeper understanding of the perspectives to be shared is needed on the side of the designers, therefore especially marginalised groups need to be empowered to create their own IDNs to allow them to benefit from the art forms potential to raise awareness and create empathy.

When discussed against the counter-narrative thematic clusters (Table 4) one finds the following distribution of the papers presented in this special issue.

CN Cluster 1 delves into the concept of ‘Counter-narratives as Narrative Inquiries’, exploring how they transcend traditional approaches to inquiry by delving into social realities and lived experiences. Euteneuer’s article contributes to this cluster by discussing a shift towards narrative inquiries that actively engage users in interactive and participatory storytelling. The author discusses research-based IDNs as a means for academic researchers to spread important messages while fostering a deeper understanding of research subjects. Through them, researchers, particularly undergraduate students, can make use of software to create interactive narratives that contextualise their research in terms of systems thinking and audience-based reasoning. This approach allows for a more profound exploration of research subjects and facilitates engagement with broader audiences, making IDNs a powerful tool for counter-storytelling that challenges dominant narratives. Taylor-Giles and Turner’s article also aligns with this cluster, as it revisits the notion of liminality as a threshold state and explores the potential of interactive digital narratives and video games to scaffold dramatic narrative identity. By analysing games like Hideo Kojima’s Death Stranding and Playmestudio’s The Signifier, the authors highlight the importance of embodiment and vulnerability in fostering empathy and a sense of closeness between players and their on-screen representations. This emphasis on embodiment mirrors the core aspects of counter-narratives that seek to challenge dominant narratives by presenting alternative perspectives rooted in lived experiences and emotional engagement.

CN Cluster 2 centres on counter-narratives as acts of resistance and opposition to dominant cultural narratives. Two articles align with this cluster: one authored by Barbara and Haahr, and the other by Ross Dionne, Sacy, and Therrien. Barbara and Haahr’s article connects to this cluster by exploring how interactive narratives can favour character narratives as a form of resistance to hegemonic agency. The study draws from the final episode of Marvel’s She-Hulk: Attorney at Law series, exemplifying how agency can be used to challenge established narratives. This aligns with the aforementioned concept of counter-narratives as ‘naming one’s own reality’ and asserting one’s voice against normalised dialogues that perpetuate stereotypes. However, the authors critically analyse the concept of interactivity, cautioning against the illusion of control provided to users and how it can be used to reinforce hegemonic power structures rather than countering them. Ross Dionne, Sacy, and Therrien’s article highlights how visual novels offer safe spaces for exploration, allowing various identities, including queer identities, to be portrayed in compassionate and humorous ways. By creating alternative discourses within these games, the authors showcase how counter-narratives can disrupt prevailing belief systems and demonstrate transformative potential. This aligns with the resistance and opposition aspect of counter-narratives, where marginalised groups use storytelling to challenge existing power dynamics and expose the irony in prevailing civil rights doctrines.

In CN Cluster 3, the focus is on empowerment and agency through counter-narratives, particularly for historically marginalised communities. The contributions of three articles can be associated with it: the one authored by Poirier-Poulin, that by Ross Dionne, Sacy, and Therrien, and that by Taylor-Giles and Turner. Poirier-Poulin’s article contributes to this cluster by analysing trust as a theme in the visual novel A Summer’s End – Hong Kong 1986. The author adopts a discerning perspective concerning trust, queer representation, and counter-narrative, deftly interweaving these elements into a compelling narrative of queer love. IDNs can give space to positive portrayal of queer individuals and relationships, affording them authentic representation with due respect to their complexities. This conscious and mindful approach towards queer representation serves as a counter-narrative that boldly challenges the long-established heteronormative norms pervasive in the 1980s society. Ross Dionne, Sacy, and Therrien’s article emphasises how visual novels serve as a conduit for exploring various identities that are often not well represented in compassionate stories and environments. By contextualising these alternative discourses in the Japanese market, the article highlights the transformative power of counter-narratives that challenge established assumptions and offer safe spaces for exploration. Through humour and unapologetic storytelling, the authors discuss how narratives can address real traumas while also using laughter as a defence mechanism. They create spaces for understanding, belonging, and positive representations of diverse relationships, encouraging players to explore and appreciate the complexity of queer experiences. Finally, Taylor-Giles and Turner’s article contributes by discussing the vulnerability and closeness that can be achieved between players and player characters in IDNs. By emphasising the importance of embodiment and player-character co-desire, the article highlights how IDNs enable participants to actively influence the unfolding experience and contribute to the instantiation of stories.This empowerment of participants aligns with the concept of counter-narratives offering alternative perspectives and empowering marginalised groups to reclaim their agency and tell their own stories. The game encourages players to empathise with characters, reinforcing their position as dramatic agents and increasing player engagement. Liminality of players is explored as dual entities – both as characters within the game world and as real individuals controlling those characters. They engage in moments of meaning-making and meaning-breaking, breaking the compact between the player and her in-game character to create a new and stronger bond. Counter-narratives challenge the conventional storytelling norms by delving into themes of identity, reality, and interstitial identities that transgress binary states. The dynamic connection between narrative identity, emplotting, and embodiment is a central point of discussion.

6. IDNs as Counter-narratives

The contributions collectively illustrate how IDNs can challenge dominant discourses, disrupt prevailing ideologies, and offer alternative perspectives that challenge stereotypes and hegemonic power structures.

What emerged from the study is that counter-narratives and IDNs share commonalities and intersect in various ways, highlighting their relationship within the broader context of storytelling and narrative expression. On the one hand, IDNs allow indeed manifestation and emergence of urgent or pressing/virulent topics from perspectives that differ from the hegemonic narrative, acting as interactive systems of representation and reduction (Geertz, 1973; Goffman, 1974) able to welcome meaningful and engaging stories. On the other hand, counter-narrative and counter-storytelling as narratives advancing the point of those who have been historically marginalised go far beyond telling the stories of those in the margins (Miller et al., 2020). Moreover, while counter-narratives empower and provide agency to communities from the dominant perspective and thus contribute to multiperspectivity (Hartner, 2014), IDNs express identity and perspective while allowing interaction and participation in the story.

As such, both can play an important role in promoting sustainability and responsibility, being a vehicle for expressing identity and valuing diversity. Counter-narratives serve as narratives that challenge and oppose dominant or master narratives, as explored in the set of definitions presented in Table 3. They aim to expose and critique normalised dialogues (DeCuir & Dixson, 2004), deconstruct power structures, and provide alternative viewpoints (Mora, 2014) to challenge established belief systems. In doing so, counter-narratives empower people at the margins by giving voice to silenced populations (Miller et al., 2020), addressing issues of equity, revealing structural inequalities, reshaping narratives, and promoting social justice (Lueg et al., 2020). IDNs constitute a distinct form of narrative expression in the digital realm (Koenitz, 2015b). As outlined in the set of definitions in Table 1, IDNs involve users actively creating and influencing dramatic storylines through their actions, be it assuming character roles, issuing commands, or manipulating the virtual world (Riedl & Bulitko, 2012b). IDNs fuse artistic vision with technology (Koenitz et al., 2015), challenging traditional assumptions about narrative by incorporating interactivity, malleable narratives enabled by digital media (Koenitz, 2015b), and the audience’s active role in shaping the narrative experience.

The connection between counter-narratives and IDNs becomes evident when considering their shared emphasis on resistance, alternative viewpoints, and the disruption of dominant narratives. Counter-narratives, as a form of resistance and opposition, challenge dominant cultural narratives and offer alternative perspectives. Similarly, IDNs challenge traditional assumptions about narrative by providing platforms for the audience’s active role, enabling them to shape and influence the unfolding experience. Furthermore, counter-narratives and IDNs are driven by a desire to bring societal change. Counter-narratives are creative and innovative forces promoting progress, development, justice, and accessible resources. Similarly, IDNs aim to generate compelling stories based on user input, often with entertainment, education, and training applications. By empowering individuals and communities to share their stories and engage in interactive storytelling, both counter-narratives and IDNs contribute to broader social transformations.

In summary, counter-narratives and IDNs intersect in their shared goals of challenging traditional assumptions, empowering marginalised communities by giving them agency and providing alternative perspectives that challenge established power structures. While Counter Narratives primarily operate in the realm of narrative inquiry and critique, IDNs provide a technological platform for expressing and exploring alternative narratives. Together, they offer valuable insights into the power of storytelling, interactivity, and participatory processes in shaping our understanding of the world and fostering inclusive and diverse narratives, critical engagement, and promoting social change.

The analysis of the curated articles of this special issue reveals a notable disparity in the visibility of certain marginalised groups compared to others. While some groups find representation and recognition within IDNs, there are still underrepresented communities whose narratives are not adequately portrayed. This observation underscores the importance of disseminating knowledge about the tools and design strategies employed in IDNs, particularly to those individuals and communities who remain relatively unnoticed or overlooked in mainstream societal awareness.

By sharing knowledge about the creation and implementation of IDNs, we can empower these marginalised groups to tell their own stories and share their unique perspectives through the medium. Equipping them with the necessary tools and understanding of design strategies will enable them to participate actively in shaping the narratives within IDNs and foster a more diverse and inclusive landscape of interactive digital storytelling. This knowledge-sharing process can act as a catalyst for empowering these communities, giving them a platform to express their experiences, challenges, and triumphs, which are often overshadowed by dominant narratives. In essence, also the identification of uneven visibility of marginalised groups should gain attention, calling for a proactive effort to bridge this gap through education and empowerment. By extending support, resources, and guidance to those who have been less represented in the medium, we can work towards amplifying their voices, fostering empathy, and raising awareness of their unique stories and struggles. In doing so, IDNs can become a more inclusive and reflective narrative form, one that truly represents the diverse tapestry of human experiences and counteracts the perpetuation of marginalisation in digital media.

7. Conclusions

In light of such premises, the eleventh issue of G|A|M|E investigates further how IDNs foster engaging experiences promoting critically informed reflection of hegemonic narratives while sensitising towards views mostly out of the mainstream. It means deepening this discussion, bringing further and broader critical understanding. We propose to expand the perspective from that of the player to that of the content and designer: from the significance of making meaningful choices and seeing their implications to counter-narratives and storytelling in games and interactive media as ways of expression.

Also confirmed by the analysis, the role of the author and/or designer, which emerges as an interpreter who shapes IDNs based on their own beliefs and perspectives, which are integrated in fictional worlds, their components and their stories are built. This promotes the idea that IDNs’ potential to transfer counter-narratives rises and falls with the individual designing person and is not a feature of IDN per se. The creators exercise their agency in shaping fictional worlds, defining the meanings and values on the ground of the world, their translation into metaphors and how they are shaped as narrative components, thus embedding their unique viewpoints into the very essence of the world. Poirier-Poulin, and Taylor-Giles and Turner further contribute to this topic with complementary perspectives. Poirier-Poulin highlights the significance of trust in fostering meaningful connections between players and characters created, exploring the relationships that can be activated and how they impact the overall experience. Similarly, Leanne Taylor-Giles and Jane Turner emphasise the importance of player-character co-desire and embodiment, which depends on the designer’s intentional choices and creative vision, which is then object of alteration due to the interaction with the players and their choices. These examples underscore the notion that IDNs’ potential to transfer counter-narratives lies not solely in the medium itself but also in the thoughtful curation and design decisions of the individual crafting the narrative. Together with the understanding of the story, the process of interpreting meanings entailed in the story, its unfolding, and engagement possibilities can be regarded as one of the modalities through which the user participates in understanding the significance, negotiating the meaning of the experiences (Bruner, 1990, 1991).

Given this premise, the issue digs into interactive storytelling and digital narratives (IDNs) to challenge the hegemonic narrative as a dominant perspective. IDNs are intended to strengthen their bonds with audiences which acquire possibilities of interaction with the content to different extents. In particular, they surface as challenging spaces to explore, discuss, and question relevant social topics.

Together with the understanding of the story, the process of interpreting meanings entailed in the story, its unfolding, and engagement possibilities can be regarded as one of the modalities through which the audience-turned-participant (Koenitz et al., 2015, p. 1) participates in understanding the significance of the experience.

References

Arseth, E. (1997). Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Aarseth, E. (2012). A Narrative Theory of Games. Proceedings of the International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games, 129–133. https://doi.org/10.1145/2282338.2282365

Ackermann, J., Egger, B., & Scharlach, R. (2020). Programming the Postdigital: Curation of Appropriation Processes in (Collaborative) Creative Coding Spaces. Postdigital Science and Education, 2(2), 416–441. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-019-00088-1

Aha, D., & Coman, A. (2017). The AI Rebellion: Changing the Narrative. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 31(1). https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v31i1.11141

Ammanabrolu, P., Broniec, W., Mueller, A., Paul, J., & Riedl, M. O. (2020). Toward Automated Quest Generation in Text-Adventure Games.

Ammanabrolu, P., Cheung, W., Tu, D., Broniec, W., & Riedl, M. (2020). Bringing Stories Alive: Generating Interactive Fiction Worlds. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Interactive Digital Entertainment, 16(1), 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1609/aiide.v16i1.7400

Ammanabrolu, P., & Riedl, M. O. (2021). Situated language learning via interactive narratives. Patterns, 2(9), 100316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patter.2021.100316

Anderson, B. R., Karzmark, C. R., & Wardrip-Fruin, N. (2019). The Psychological Reality of Procedural Rhetoric. Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games. https://doi.org/10.1145/3337722.3337751Andrews, M. (2004). Opening to the original contributions: Counter-narratives and the power to oppose. In M. Bamberg & M. Andrews (Eds.), Considering counter-narratives: Narrating, resisting, making sense (Vol. 4, pp. 1–6). John Benjamins Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1075/sin.4.02and

Bogost, I. (2007). Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames. The MIT Press.

Bogost, I. (2021). Persuasive Gaming in Context (T. De La Hera, J. Jansz, J. Raessens, & B. Schouten, Eds.; pp. 29–40). Amsterdam University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9789048543939-003

Bruner, J. (1990). Acts of Meaning. Harvard University Press.

Bruner, J. (1991). The Narrative Construction of Reality. Critical Inquiry, 18(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1086/448619

Ciancia, M. (2018). Transmedia Design Framework: Design-Oriented Approach to Transmedia Practice. FrancoAngeli.

Cohen, J. (2001). Defining identification: A theoretical look at the identification of audiences with media characters. Mass Communication & Society, 4(3), 245–264.

Coleridge, S. T. (1817). Biographia Literaria: Or, Biographical Sketches of My Literary Life and Opinions. Rest Fenner, 23, Paternoster Row.

Crawford, C. (2004). Chris Crawford on Interactive Storytelling. New Riders.

DeCuir, J. T., & Dixson, A. D. (2004). “So When It Comes Out, They Aren’t That Surprised That It Is There”: Using Critical Race Theory as a Tool of Analysis of Race and Racism in Education. Educational Researcher, 33(5), 26–31. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X033005026

Delgado, R. (1995). The Rodrigo chronicles: Conversations about America and race. NYU Press.

Dubbelman, T., Roth, C., & Koenitz, H. (2018). Interactive Digital Narratives (IDN) for Change. In R. Rouse, H. Koenitz, & M. Haahr (Eds.), Interactive Storytelling (pp. 591–602). Springer International.

El-Nasr, M. S. (2004). A User-Centric Adaptive Story Architecture: Borrowing from Acting Theories. Proceedings of the 2004 ACM SIGCHI International Conference on Advances in Computer Entertainment Technology, 109–116. https://doi.org/10.1145/1067343.1067356

Fernández-Vara, C. (2014). Introduction to Game Analysis. Routledge.

Freiknecht, J., & Effelsberg, W. (2020). Procedural Generation of Interactive Stories Using Language Models. Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games. https://doi.org/10.1145/3402942.3409599