Sarah Lynne Bowman (Uppsala University), Josefin Westborg (Uppsala University), Kjell Hedgard Hugaas (Uppsala University), Elektra Diakolambrianou (Institution for Counseling and Psychological Studies, Athens), Josephine Baird (Uppsala University)

Abstract

While interest in the use of analog role-playing games as a tool for personal and social change has increased in recent years, best practices in design are still in development. This paper will briefly introduce analog role-playing games, describe this movement toward design for transformative purposes, and briefly introduce theoretical concepts such as safety, intentionality, bleed, alibi, ritual, identity, and transformational containers. We will discuss some of the known benefits of transformative play, such as the development of skills in perception checking and empathy, as well as drawbacks described in the research regarding playing marginalized identities the player does not share. Overall, this paper gives general recommendations for design work when aiming to maximize the transformative potential of these games, especially regarding different strategies for reflection, processing, and integration.

Introduction

Interest in using analog role-playing games (RPGs) as a medium for transformation is increasing. Such interest arises from a participant who has experienced leisure role-playing games and has either witnessed or experienced some sort of significant positive change. Such players then wonder how such games might be used in applied settings. For example, role-players may run games with important themes to raise awareness on social issues for participants engaging in their leisure time (see e.g., Stenros & Montola, 2010; Groth, Grasmo, & Edland, 2021). Such works may even be commissioned by funding bodies, then shifting them into non-formal education for political or social aims (see e.g., Baltic Warriors, 2015; Halat Hisar, 2016). But designing for transformation is difficult and best practices are not yet well established. At the Transformative Play Initiative, we have worked to fill this gap by developing theory and in practice. As a research collective, our members have published academic texts, created courses, and designed and ran transformative analog role-playing games for thousands of participants over the years. Here, we have gathered insights for design and practice to maximize the transformative potential of analog role-playing game in the hope that others can build upon and further evolve it.

In this article, we will start by introducing analog role-playing games and transformative role-playing games. We will then share our definition of transformation and how we categorize different types of applied RPGs. Thereafter, we will introduce components and theoretical concepts that we have found crucial in designing for transformation. Finally, we will discuss some of the challenges around inclusion when designing for transformation before concluding the paper. More information about our model and theoretical framework can be found in our textbook (Bowman, Diakolambrianou, and Brind, eds., in review).

Analog Role-Playing Games

Analog role-playing games are “co-creative experiences in which participants immerse into fictional characters and realities for a bounded period of time through emergent playfulness” (Transformative Play Initiative, 2022c). For our purposes, analog role-playing games include tabletop, live action role-playing (larp), and Nordic and American freeform. Tabletop RPGs are usually played sitting at a table, sometimes including dice, character sheets, and miniatures. They tend to be less physical and more verbal, with players often shifting between the first person and third person when describing their character’s actions. Larp is often more physically embodied role-playing, sometimes including costumes, props, and special locations. Nordic and American freeform developed as a “middle child” between tabletop and larp, featuring aspects of both but also emerging as their own respective mediums (Westerling, 2013).

Of course, depending on the style of game, the genre, and the playgroup, these definitions can shift. Larp tends to be more “physically embodied” in that players are expected to move and act out the actions of the character to greater or lesser degrees, but all play is technically an embodied experience. Larps set in a meeting room can look identical to a tabletop game given the right set of circumstances. Some of these games have no costumes, dice, or even character sheets.

Furthermore, while analog games get their name due to their non-digital nature and generally do not require a computer interface to play, these distinctions are becoming less and less meaningful with the rise of popular livestreaming of RPGs (Jones ed., 2021); play-by-post and forum play (Zalka, 2019); online tabletop (Sidhu & Carter, 2020); and online larp (Reininghaus, 2019). Indeed, such hybrid forms can even be experienced as transformative by viewers through vicarious experience and social bonding (Lasley, 2021). For our purposes, we will include in “analog” any role-playing that allows for fairly free spontaneous improvised co-creation within the framework of the game rules, unlike most digital RPGs that are heavily mediated by the computer interface and limited coded options for engagement.

Due to these differences in these respective mediums, we will center theory and practices surrounding analog RPGs specifically, while acknowledging that these discourses take place within larger cultural conversations and practices. Such clarifications not only help us situate our work within these broader conversations, but allow us to be precise about the exact phenomena we are investigating.

Transformative Role-Playing Games

Now that we have provided our definition of analog role-playing games, in this section, we will explore transformative analog RPGs.

Tabletop role-playing games have become an increasingly popular medium for educational interventions in diverse locations such as the US (Garcia, 2016; Cullinan & Genova, 2023), Canada, Cambodia, (Genova 2024) and Indonesia (Winardy & Septiana 2023) to name a few. Tabletop is becoming especially popular in therapeutic interventions (Gutierrez, 2017; Bean et al. eds., 2020; Connell, 2023; Hand 2023; Kilmer et al., 2023; Yuliawati, Wardhani, & Ng 2024). Larps are also increasing in use in both sectors, with experiments occurring in therapeutic practice (Ball, 2022; Bartenstein, 2022, 2024; Diakolambrianou, 2021; Transformative Play Initiative, 2022a) and edu-larp developing as its own pedagogical subfield (Bowman, 2014; Fey, Dagan, Segura, & Isbister, 2022; Johansson et al., 2024). These developments include conferences devoted to educational RPGS held in the Nordic countries from 2014-present (see e.g. Nordic Larp Wiki 2023; Solmukohta, 2024), Italy (Geneuss, Bruun, & Bo Nielsen, 2019), the US (Bowman, Torner, & White, eds., 2016, 2018), and Brazil (Iuama & Falcão, 2021; Role Simposio, 2024), as well as conferences on related role-playing activities such as Reacting to the Past (see e.g., Reacting Consortium, 2024; Hoke & Risk, in press). Research is also increasing with regard to these developments, especially in therapeutic RPGs, to the degree that a handful of review pieces have recently been published summarizing the literature (Henrich & Worthington, 2021; Arenas et al., 2022; Baker, Turner, & Kotera, 2022; Yuliawati, Wardhani, & Ng 2024).

In order to best capture what design practices encompass all of these outgrowths, we define transformative analog role-playing games as: RPGs designed for the purpose of encouraging personal and/or social change arising from leisure play and discourse communities (cf. Daniau, 2016).

While role-playing games are a unique outgrowth of many subcultural groups — e.g. wargaming in the US (Petersen, 2012), Tolkein fandom in Russia (Semenov, 2010) — role-playing as a technique far precedes many of these most recent developments. The term originated from J. L. Moreno, who developed psychodrama and sociodrama (Fantasiforbundet, 2014). Role-playing has also been used in education, especially in the field of simulation, which is a popular training method in health care, military, business, government training, and traditional educational classrooms (Bowman, 2010). Since these uses of role-playing as a practice do not arise from leisure play and RPG discourse communities, but rather from education and therapy, we consider them “cousin forms” (Bowman, 2014).

While the basic act of enacting a character in a co-created fictional world is much the same regardless of community, the practices, norms, discussions, and innovations within each group differ. Analog role-playing games often have passionate and vibrant discourse communities surrounding them, e.g. the Forge and Story Games diaspora in tabletop (White, 2020) and the Nordic Larp discourse originating from the Knutepunkt/Solmukohta conferences and their respective yearly publications (Nordic Larp Wiki, 2022). Within these communities, even the term “leisure” can be called into question, particularly with the amount of labor required of facilitators and players alike (Jones, Koulu, & Torner, 2016) to help create a good experience, not to mention the work involved in contributing to the popular discourse itself, which has often taken place on social media or forums rather than more traditional publication channels. Some of this volunteer work has nevertheless received a degree of legitimacy, e.g., articles the Knutepunkt and Wyrd Con Companion Books or the the web magazine Nordiclarp.org, which are often cited as key texts in role-playing game studies (Harviainen, 2014).

Meanwhile, digital games have their own lexicon, theory, and practice around transformative play (Tanenbaum & Tanenbaum, 2015), see e.g., Serious Games (Chen and Michael, 2006), Games for Change (2022), gamification (Deterding et al., 2011), game-based learning (Plass, Mayer, & Homer eds., 2020), and deep games (Rusch, 2017). While our topic is informed by these game-related discourses, including more traditional educational or therapeutic concepts, for the purposes of this paper, we will limit our discussion to discourses related to applied analog role-playing games specifically. Our work is part of a growing body of literature that situates practices of transformative role-playing game design and implementation alongside these other cousin practices, (Burns, 2014; Linnamäki, 2019; Diakolambrianou & Bowman, 2023), hopefully resulting in the “best of all worlds.”

Transformation

Terms related to transformation are used rather liberally to apply to a range of different experiences. They are used in multiple fields, such as business (Blumenthal & Haspeslagh, 1994), tech (Gong & Ribiere, 2021), and education (Boyd & Myers, 1988). Even within the field of games, transformation is used for everything from players’ ways of interacting with the game (Magnussen & Misfeldt, 2004), learning (Barab et al., 2010), and how games can help the production industry become more human-centric (Brauner & Ziefle, 2022). With these vastly different usages of the concept, building on different fields, transformation takes on different meanings. Our definition is drawn from John Paul Lederach’s (2003) conceptualization of conflict transformation, “engaging [oneself] in constructive change initiatives that include and go beyond the resolution of particular problems.” Inherent to this concept is the word “initiative,” which insinuates that the participants have an active involvement, rather than a passive, unconscious, accidental or incidental change. We extend this definition beyond conflict to refer to initiatives that move beyond specific moments in a game to effect longer-term change.

We define transformation as both (Transformative Play Initiative, 2022d):

- A prolonged and sustained state of change; a shift in one’s state of consciousness that is not temporary but has lasting after-effects.

- A process, or series of processes, that lead to growth: the growth can be personal, interpersonal, social, or even societal and cultural.

The first definition refers to an incident catalyzed by a game that leads to a major change that is prolonged and sustained after the game. An example might be a player self-advocating for the first time in a larp (New World Magischola, 2016), then feeling more confident standing up for themselves in daily life.

The second definition refers to transformation as a process or series of processes. This definition is inspired by conflict transformation, which does not see change as occurring in a linear path, but rather as a spiral of change processes unfolding over time (Lederach, 2014). These processes are circular in nature and may not always look like “progress”: e.g., they may move forward, hit a wall, move backwards, things collapse (p. 38-41). A common example is a person discovering their authentic gender identity by playing it in a game or experiencing a supportive RPG community and deciding to transition as a result, whether immediately or in the future (Moriarity, 2019; Baird, 2021; Edland & Grasmo, 2021; MacDonald, 2022; Sottile, 2024). The role-playing experience likely catalyzed change processes that were already underway, but had yet to be able to find expression. Furthermore, change after the game is still a series of processes, e.g., the process of deciding when and to whom to come out; the process of changing one’s names and pronouns, etc. The framing of change processes also acknowledges change as occurring within a complex social landscape, progress as complicated, and transformation as happening in fits and starts due to various forms of internal and external resistance.

Therefore, when inspired by role-playing experiences, transformation can be:

- A state that alters a person’s view of themselves, others, or the world in significant ways,

- A state that shifts the way a person relates to others interpersonally, and/or

- A state that has the potential to shift social and cultural dynamics in ways that can build toward greater awareness, peace, and justice.

This final point emphasizing peace and justice situates our definition of transformation as progressive in nature. We are not interested in facilitating experiences that incentivize or more deeply intrench participants in reactionary, exclusionary, or otherwise antisocial practices, nor are we interested in experiences that encourage growth for privileged members of society while further stratifying and providing unjust conditions for others. We will discuss issues that can arise when designing with these intentions in mind at the end of this paper.

Types of Applied Role-Playing Games

We consider all games designed for a transformative purpose as “applied” in the sense that the medium of role-playing is being applied with a specific outcome in mind. In terms of applications, we define three categories of transformative analog role-playing games. The distinctions mainly apply to the type of facilitation offered, where, and by whom, as well as the framing designed around the game.

Transformative leisure role-playing games are designed and played for a variety of reasons, mostly personal and individualized ones, even if the game has a specific goal in mind, e.g., an art game sharing the designer’s personal experience with a challenging life event. As mentioned above, the term “leisure” can be a bit misleading, as leisure RPGs and the activities surrounding them can often involve intense amounts of work (Jones, Koulu, & Torner, 2016); in some cases, players even enact the same set of skills or roles in leisure games used in their professional life (Homann, 2020). However, we can consider a game transformative leisure if participants engage in it voluntarily in their free time.

Therapeutic role-playing games are designed and played with explicit therapeutic goals in mind, i.e., goals pre-established between clients and facilitators to foster psychological growth. Critically, we define games as therapeutic only then they are facilitated with emotional support from a mental health paraprofessional or professional, i.e., a coach, therapist, social worker, mental health first aid worker, community healer, etc. Furthermore, this support occurs in the context of a therapeutic agreement in which the client and the professional agree to engage in psychological processing before, during, and after the game. Such long-term agreements have special expectations with regard to psychological care that would not be appropriate or possible in other settings. While therapeutic RPGs may be voluntary, they are sometimes mandatory, e.g., a neurodiverse adolescent required to go to therapy by their parents or a person ordered by the court system to work on anger management with a professional.

Educational role-playing games are designed and played with explicit and/or implicit educational goals in mind. These goals are usually framed as explicit learning objectives or outcomes, which may be based on the existing curriculum (Geneuss, 2021; Cullinan & Genova, 2023; Westborg, 2023) or other learning goals (Transformative Play Initiative, 2024). The game is either run by one or more educators or in collaboration with them, e.g., visiting a classroom to run the larp under the regular teacher’s supervision. Educational role-playing games may be voluntary, e.g., visitors at a museum choosing to engage in an educational larp about history, but they are often mandatory, e.g., larps run for young students in classrooms during school time (Lundqvist, 2015).

These three categories are related but somewhat distinct. We use the phrase “somewhat distinct” here because the experience of transformative play does not fit neatly into specific settings or even expectations. Players often describe leisure role-playing experiences as “therapeutic,” sometimes even joking about it as “free therapy” (Bowman, 2010). Furthermore, recent studies have featured results about leisure RPGs having positive benefits on mental health in non-therapeutic (Causo & Quinlan 2021; Walsh & Linehan 2024) or quasi-therapeutic contexts (Lehto 2024), i.e., designed or facilitated under therapeutic consultation, but without the expectation of ongoing support from a paraprofessional.

Technically, any activity can be therapeutic if it has a positive impact on one’s mental health, even leisure games designed for entertainment and educational games. For example, leisure RPGs can be helpful for queer players to explore and express their identities in a safer space (Baird, 2021; Tanenbaum, 2022; Femia, 2023; Sottile, 2024), although some communities fail to support queer players consistently (Koski, 2016; Stenros & Sihvonen, 2019). For our purposes, transformative is a more accurate term for such impacts if the activity is not undertaken within the context of a care agreement between a client and a mental health professional.

The term “education” is similarly confusing, as role-playing games can occur in informal, non-formal, and formal educational environments (Baird, 2022; Westborg 2023). Furthermore, many of the same skills are trained in these respective contexts, e.g., social skills training occuring in therapeutic (Kilmer et al., 2024), educational (Bowman, 2014), and leisure (Katō, 2019) settings, as well as in-between spaces such as after-school programs (Transformative Play Initiative, 2024) and summer camp activities (Hoge, 2013; Living Games Conference 2018), blurring the lines further.

Finay, while this paper focuses on designing games from the ground up with transformative goals in mind, a more common practice is to hack an existing game to maximize its transformational potential and shape the narrative within it or the framing around it, i.e., the workshop and the debrief (Transformative Play Initiative, 2022b). For example, due to its ubiquity and popular appeal, Dungeons & Dragons (1974) is often used in a simplified form in therapeutic practice with specific scenarios adapted or designed based on agreed-upon goals (Connell 2023; Kilmer et al. 2023). Such games often include framing that supports therapeutic goals, e.g., processing questions asked either within the group or one-on-one before, during, and after the game.

Designing to Maximize Transformational potential

While transformation cannot be confined to any one setting — or even guaranteed by any set of practices — we can aim to refine the processes by which we design, implement, and play role-playing games to maximize their beneficial impacts. In our work, we have found that there are certain components and theoretical concepts that can help maximize the potential for transformative impacts and understand the processes that enable them.

Contextual components supporting transformative processes

Regardless of the type of transformative role-playing game, we believe the most important components for maximizing the potential for transformative impacts for designers, facilitators, and players alike are the following:

- Community: Following Wilfred Bion (1959; 2013) and D. W. Winnicott (1960), our model emphasizes cultivating communities around games that help establish and maintain a transformational container (Bowman & Hugaas, 2021; Baird & Bowman, 2022). Some players may have transformative experiences within games but not feel fully supported by the community playing them, e.g., having a gender affirming experience within a tabletop game but not feeling supported in coming out by one’s co-players (Baird, 2021). Therefore, the container must feel secure enough to hold the alchemical process of change.

- Intentionality and goal setting: Creators should have clear intentions and goals throughout the process, with all design and implementation choices focused on these goals. Examples of types of transformative goals include (Bowman & Hugaas, 2019):

-

- Educational Goals: Critical thinking, systems thinking, problem solving, perceived competence, motivation;

- Emotional Processing: Identity exploration, identifying/expressing emotions, processing grief/trauma, practicing boundaries;

- Social Cohesion: Leadership, teamwork, collaboration, practicing communication skills, community building; and

- Political Aims: Awareness raising, perspective taking, empathy, conflict transformation, paradigm shifting;

These goals should be clearly communicated to the participants so that they can enter the experience with these intentions in mind. This practice onboards all participants onto the notion that transformative impacts are normative in this space rather than something to be feared or avoided. Ideally, these goals align with meaningful actions characters can take within the game (Balzac, 2011). Deception should be kept to a minimum or removed completely (Bowman & Hugaas, 2019). Clarifying intentionality before, during, and after a game can help align everyone within the play community toward a shared social contract, e.g., having a pronoun correction workshop (Brown, 2017) or expressly stating that a game is intended for exploring or expressing non-normative genders (Baird, Bowman, & Thejls Toft, 2023).

- Embracing the unexpected: Role-playing games are a spontaneous, improvised medium, which means players will likely take the game in directions unforeseen by the designers. Play can feel chaotic and uncontrollable, especially to facilitators accustomed to more traditional forms of learning, e.g., school teachers (Harder 2007; Hyltoft 2010). Unforeseen transformative impacts may occur through emergent play, while initial goals may not be reached. Such outcomes should be embraced as part of the beauty of the medium.

- Reflection and processing: These games should encourage, prioritize, and scaffold off-game reflection, connecting significant moments within the game to takeaways meaningful to daily life, e.g., important social issues, political events, personal challenges, interpersonal dynamics. Games run without built-in moments of processing are less likely to impact the players in a consistent fashion; in fact, failure to debrief can lead to the goals of the scenario backfiring (Aarebrot & Nielsen, 2012). Facilitators can also help cultivate a longer-term transformational container (Baird & Bowman, 2022) within which players can help one another process and achieve goals long after the game experience has ended, e.g., maintaining shared online communities for discussion and holding reunion events.

- Safety: While no experience can ever be considered fully safe, the perception of safety is important to establish and maintain in role-playing communities. Safety enables participants to lower their vigilance and surrender more deeply to playfulness as a central part of the transformative process. Surrender here is distinct from submission; the player still retains agency, but is able to take risks through play they might otherwise find unwise (Baird & Bowman, 2022). Safety necessitates enthusiastic consent, establishing boundaries, calibration, and other forms of negotiation and self-advocacy (Koljonen, 2020). Situations in which play is forced on players without negotiation or agreement may backfire in terms of transformative goals, e.g., lack of transparency of what character actions mean in a game (Torner, 2013). Consent has particular challenges in mandatory play situations, such as in a school setting (Lundqvist, 2015), so care should be taken to ensure participants do not feel coerced to push past their boundaries due to uneven power dynamics or expectations of assessment. In such situations, players can be offered varying degrees of engagement within the game to reduce pressure, the ability to opt-out, the agency to request non-essential content to be removed, or an alternative assignment with equivalent learning goals. Leisure role-playing games already have established methods for many of these practices, including Session 0s, safety mechanics (Reynolds & Germain, 2019); consent and calibration discussions (Koljonen, 2020); and post-game debriefing (Brown, 2018) among others.

These important factors help shape the transformational container that enables play. The next section will develop this theoretical framework to describe the mechanisms that make the act of role-playing itself rife for processes of transformation, as well as framing and integration practices that aid in the transfer of knowledge and distillation of takeaways that can lead to long-term change. Understanding these concepts can help designers optimize their choices with respect to intended goals.

Mechanisms of transformation in design, implementation, and play

Alibi and Identity

Once the transformative container of play is established, players leave their default identities from their external lives and adopt new characters within the fictional world through the alibi of play (Deterding, 2018). Alibi allows participants to act within the game with lessened social consequences, which can encourage greater risk taking and willingness to fail. Alibi is established as part of the game’s social contract (Montola 2010), along with other agreements and rules about appropriate ways to engage within the magic circle of the game (Huizinga, 1958; Salen & Zimmerman, 2003). [1] However, in our mode, alibi should not be so strong that players are encouraged to completely disassociate their daily identities with their characters’ or compartmentalize the play experience as separate from their lives, as such tendencies can interrupt processes of change (Bowman & Hugaas, 2021).

Role-playing games allow us to experiment with identity, accessing parts that can sometimes paradoxically feel more authentic than our daily identities (Winnicott, 1971). Ideally, players are encouraged to thoughtfully reflect upon the parts of their characters they would like to take with them and leave behind after play, not just as a standard de-roling technique (Brown, 2018), but as an extensive process of wyrding the self (Kemper, 2020): actively shaping their sense of self into what they would like it to be moving forward. Similarly, a person can use play to restory their life (Tanenbaum, 2022), actively structuring a life narrative that is more empowering for them, which can thus affect their narrative identity (Bowman & Hugaas, 2021; Diakolambrianou & Bowman 2023).

Change often involves transformative learning in some way. Transformative learning is a complicated and sometimes exhausting process; we must confront new material and figure out whether or not to integrate it into our worldview, whether consciously or unconsciously (Illeris, 2006, 2009, 2013). Complications with such learning can occur, such as cognitive dissonance, i.e., when new information contradicts our existing model of reality or worldview (Festinger, 1957), leading to confusion and disorientation. Cognitive dissonance can trigger the identity defense (Illeris, 2006, 2009, 2013; building upon Jean Piaget): when a person is compelled to reject new information because it threatens their paradigm or is perceived to be incompatible with their identity.

However, due to the role and fiction, the transformational container of role-playing games can provide a space in which people might bypass the identity defense and explore aspects of self previously underexplored or expressed (Baird, 2021; Hugaas 2024). They can also explore ideas that might otherwise contradict their worldviews, helping them learn perspective taking and empathy building for people different than themselves (Bjørkelo & Jørgensen, 2018; Leonard, Janjetovic, & Usman, 2021). In this regard, alibi provides a protective frame (Montola 2010) in which transformative learning can occur more readily. On the other hand, lowering alibi at key moments such as character design and debriefing can assist in the process of transfer.

Ritual

The complicated nexus point of fiction and self in role-playing games holds tremendous potential for transformation, especially when combined with ritual activities within and around play that frame and deepen the role-playing experience. Ritual involves three stages (van Gennep, 1960; Turner, 1974):

- A departure from the mundane world with thorough separation and preparation,

- An entrance into an in-between “threshold” state called liminality, an in-between space that involves a temporary shift in social roles,

- A return to the mundane world with an incorporation of these liminal experiences.

For Victor Turner (1974), the ritual process creates communitas, or a sense of community through the shared mutual experience. From this perspective, the magic circle of play is literally a ritual space rather than just a concept. The before phase, or preparation, can include workshops, lectures, costuming, and other ways to prepare for the ritual. The liminal stage is the game itself (Harviainen, 2012), as players temporarily shift roles and agree to interact within a shared alternative social context. Role-playing games are especially powerful as the players often co-create this ritual space and the activities within it, unlike more traditional rituals that have been handed down over time, e.g., marriages, graduation ceremonies, and funerals. The after phase, or return, can involve deroling, debriefing, processing, and other integration practices. By understanding the mechanism of ritual, designers can more consciously and deliberately create play experiences that aid in transformation.

Bleed

What can help the transformative process is the phenomenon of bleed, when contents spill over from the player to the character and vice versa. While some players claim not to experience bleed, we consider bleed a phenomenon that is always happening, whether it has reached the player’s bleed perception threshold or not (Hugaas, 2024). Others may not noticeably experience bleed, but can still experience transformation, e.g., through post-game intellectual analysis (Bowman & Hugaas, 2019). In transformative play, we should not assume players will noticeably experience bleed, but we can still design for it in various ways, e.g., designing close to home characters that the players may find relatable (Vi åker jeep, 2007), creating intensely emotional experiences that can help bypass the identity defence.

Bleed can take many forms, including but not limited to (Baird, Bowman, & Hugaas, 2021; Hugaas 2024):

- Emotional Bleed: Where emotional states and feelings bleed between player and character (Montola, 2010, Bowman, 2013), e.g., negative experiences in play leading to animosity between players (Leonard & Thurman 2018);

- Procedural Bleed: Where physical abilities, traits, habits, and other bodily states bleed between player and character (Hugaas, 2019), e.g., how we carry ourselves, ticks, movements, reflexes; learning how to move in a way that physically exudes more sensuality or confidence;

- Memetic Bleed: Where ideas, thoughts, opinions, convictions, ideologies and similar bleed between player and character (Hugaas, 2019), e.g., values of equity embedded in structure in the game leading to players adopting these views outside of the game;

- Ego Bleed: Where aspects of personality and identity bleed between player and character (Beltrán, 2012, 2013), including archetypal contents, e.g., playing a resilient and strong queen character leading to greater confidence for the player;

- Identity Bleed: Where aspects of one’s sense of self, self-schemas, and similar identity constructs bleed between player and character (Hugaas, 2024), a process that is more comprehensive than ego bleed;

- Emancipatory Bleed: Where players from marginalized backgrounds experience liberation from that marginalization through their characters. Players can choose to steer toward such liberatory experiences as a means to challenge structural oppression (Kemper, 2017, 2020), e.g., overthrowing an oppressive structure in play leading to players processing aspects of real life oppression in their own lives;

- Romantic Bleed: When players feel attraction or even fall in love with fictional characters (Waern, 2010) and/or players (Harder, 2018) after an intense role-playing experience.

Bleed as a mechanism helps us understand pathways to transformation. We can become more aware that the frames (Goffman, 1986) of in-game and off-game experience are more porous than we may realize. From that awareness, we can then acknowledge this porousness as a space of great potential for steering (Stenros, Montola, & Saitta, 2015) toward transformative experiences. We can then use bleed as a way to unlock aspects of our life that we would like to design differently, such as our identities, our self-concepts, our communities, our paradigms, and our relationships (Bowman & Hugaas, 2021). From that point, we can integrate our role-playing experiences, including bleed, into our lives in intentional ways, and express ourselves in ways that feel more authentic as discovered through play (Winnicott, 1971). All of these processes can be considered in the design and implementation of such games.

Debriefing

Central to transfer of knowledge and integration of learning into our lives is that any insights gleaned from the game experience should be distilled as takeaways in some meaningful way. As a minimum, we emphasize the importance of structured debriefing after the game. Structured debriefing involves carving space for participants to process their experiences in a serious way. They are best run by the facilitators if possible and function as a space for three main types of reflection (Westborg, 2023):

- Emotional debriefing: Processing the emotional experience, sometimes according to goals. Emotional debriefing is common in leisure and therapeutic settings, but can also occur in educational ones;

- Intellectual debriefing: Processing according to general intellectual concepts or themes related to play, common in leisure and educational settings, but can also occur in therapeutic ones; and

- Educational debriefing: Processing according to specific learning objectives, common in non-formal and formal educational settings.

Just like all aspects of the game, the structured debrief questions are a designable surface (Koljonen 2019) that can focus the discussion on the types of growth that most align with your purpose and help the players transfer their insights out of the game. We recommend starting with one emotional debrief question for transformative games if time allows, e.g., “What was the most intense or powerful experience in the game for you?” Allowing for emotional processing first can help guide players to make space for intellectual engagement. Building in critical reflection is crucial when designing games with a transformative purpose (Crookall & Whitton, 2014). Key to the debrief, therefore, is to have plenty of time for processing presented as part of the game experience, rather than optionally tacked on at the end or left to the players to figure out themselves.

For educational games, we suggest designing debriefing questions that have additional aims in mind (Westborg & Bowman 2024):

- a) Connection: Building links between play experiences and established learning objectives or outcomes, which are often stated in advance, e.g., specific skills trained or topics explored;

- b) Abstraction: Building links between the specifics of the game to more general concepts in the outide world, e.g., democracy, feminism, evolution, or power in other contexts; and

- c) Contextualization: Educating participants further with additional materials or granular facts about topics explored in the game by adding additional context, e.g., through lectures, first-hand testimonies, or reading assignments.

As mentioned before, failure to connect the play experience to learning goals may interrupt transfer, e.g., players feeling the game was “fun” but remaining unable to place it within the larger contexts of their lives and the world around them.

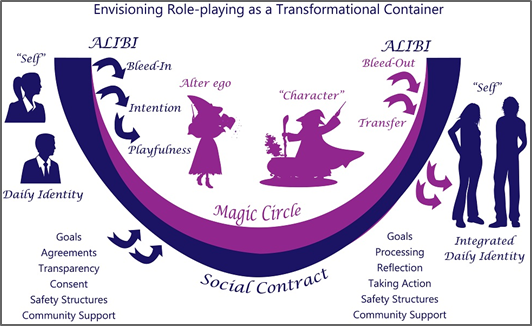

Figure 1 – The process of transformation in role-playing games and the core elements needed for cultivating transformational containers that support them (Bowman & Hugaas, 2021).

Integration

While structured debriefing is always recommended, not everyone is able to process so quickly after a game. Therefore, just like other activities within the transformational container, while debriefs should be considered part of the game structure, we recommend giving players the opportunity to opt-out of the debrief or simply pass and listen if needed.

Furthermore, debriefing is only the beginning. When considering transformation as a series of change processes, in order to sustain change over time, goal setting and post-game actions should be taken after the game to help crystallize intention into action. For example, a person may discover a leadership skill within a game they were not aware they had, inspiring them to want to explore this further. By setting a clear goal, such as signing up to run a game at their local convention for the first time, they can keep working on this newfound skill. Over time, they might even end up feeling bold enough to apply for a leadership position at work in a role that previously felt inaccessible to them.

Integration practices can include (Bowman & Hugaas, 2021):

- Creative Expression: Journaling, studio art, performance art, game design, fiction writing, storytelling, co-creation;

- Intellectual Analysis: Contextualization, researching, reframing experiences, documentation, theorizing, applying existing theoretical lenses, reflection;

- Emotional Processing: Debriefing, reducing shame, processing bleed, ego development/evolution, individual or group therapy, validating one’s own experiences, identifying and acknowledging one’s needs/desires/fears, distancing one’s identity from undesirable traits/behaviors explored in-character;

- Interpersonal Processing: Connecting with co-players, re-establishing previous social connections, negotiating relationship dynamics, sharing role-playing experiences with others, engaging in reunion activities;

- Community Building: Networking, planning events, collaborating on projects, creating new social systems, sharing resources and knowledge, establishing safer spaces, creating implicit and explicit social contracts, engaging in related subcultural activities, evolving/innovating existing social structures; and

- Returning to Daily Life: De-roling, managing bleed, narrativizing role-play experiences, distilling core lessons/takeaways, applying experiences/skills, engaging in self-care/grounding practices, incorporating personality traits/behaviors.

Participants differ in terms of which integration practices work best for them. Sometimes, a variety of approaches can be helpful. Regardless of the approach, designers and facilitators should consider offering opportunities for such practices or recommend players engage in further integration on their own as a normative part of transformative play.

Challenges with Transformative Play and Inclusion

Some tensions within the discourse surrounding games and their potential for change are difficult to reconcile entirely. Some argue that play should not have to be transformative to have value, and that demanding that play needs to be “useful” does it a disservice. Others argue that not all play is benign, and point to the ways in which it can be transgressive in antisocial ways (Stenros, 2015). Although many participants find gaming communities more inclusive than other social groups, in Western societies, RPGs are often coded as predominantly white (Trammell, 2023), cis-male (Dashiell, 2020), middle class activities, which creates a mythical norm that can feel exclusionary for people from marginalized backgrounds (Kemper 2020).

Some of the most common benefits ascribed to role-playing games are their potential for awareness raising, perspective taking, and empathy development (Bjørkelo & Jørgensen, 2018; Leonard, Janjetovic, & Usman 2021). Role-playing scenarios with heavy themes that focus on playing to lose (Nordic Larp Wiki, 2019), with value placed upon positive negative experiences (Montola, 2010), can produce meaningful discomfort (Bjørkelo & Jørgensen, 2018) in which transformative learning can occur. However, even in relatively progressive role-playing communities that actively use RPGs in these ways, some participants from marginalized groups can still feel excluded, for example through practices of cultural appropriation (Kessock, 2014); stereotyping (Cazeneuve, 2018); or feeling that their life struggles are being used as content for dark tourism: leisure experiences centered upon immersing into marginalized identities that players do not share (Nakamura 1995), or playing backgrounds of oppression, grief, or misery that the players have not personally experienced (Leonard, Janjetovic, & Usman, 2021). Even discussing such experiences as a “game” can feel exclusionary for members of the community who question whether such topics should be played or who cannot “opt-out” of such topics in their own lives (Torner, 2018).

Such tensions are not fully resolvable, but are important to consider when designing transformative games. Key questions include:

- For what populations am I designing this game?

- Who will it benefit?

- Who might it harm?

- How can I mitigate such harm?

- Who can I include throughout the process to make the game more inclusive?

As an example, a common topic of transformative role-playing games is playing the role of asylum seekers or refugees (Bjørkelo & Jørgensen, 2018). If the experience is only designed to help promote empathy in people born in the country in question, it may benefit them, and indirectly benefit refugees with whom they interact in the future. However, if no people from these backgrounds were included in the design and implementation process, there is also a chance that harm might occur if people say harmful things or portray stereotypes under the guise of “play” (Trammell, 2023) e.g., running a larp in a classroom with a mixture of students born in the country and immigrants without proper framing. In some cases, harmful beliefs might actually be reinforced, for example if a debrief highlighting the need for greater empathy is not run (Aarebrot & Nielsen, 2012). Furthermore, players from marginalized backgrounds may feel less welcome in the container under such conditions and find it necessary to develop special techniques to be able to navigate such spaces (Kemper, Saitta, & Koljonen, 2020).

Some ways to mitigate harm include establishing and maintaining safety throughout the game, e.g. having a safety team member available, safety mechanics to signal issues that arise, and structured debriefs that allow space for sharing powerful emotions that arise. By being clear about the goals and creating a transformative container, the fallacy of play (Mortensen & Jørgensen, 2020) — the idea that actions taken in play are harmless — can be addressed early on and help set intentionality to focus on transformation. Furthermore, designers and facilitators might hire experts on the topic, cultural consultants, and sensitivity readers, ideally from the backgrounds in question, to evaluate the materials. An even better approach is to co-design the game materials with them and involve them in the facilitation process (Kemper, 2017; Leonard, Janjetovic, & Usman, 2021; Mendez Hodes, 2019).

Conclusion

This short summary of our recent research is meant to provide a condensed roadmap for the study of transformative analog role-playing game design. We have discussed the definitions of our terms, including the distinctions between transformative leisure, therapeutic, and educational. We have discussed the construction of the transformational container, including the components within it that are important to foster for desired impacts to occur: ritual, bleed, alibi, processing, safety, integration, etc. We have discussed some of the critiques of the transformative play approach and offered some recommended methods to address them. Ultimately, we consider this a jumping off point rather than a destination, as we are truly only scratching the surface of analog role-playing games’ transformational potential.

End Notes

[1] While the boundedness of the magic circle as a discrete entity has been heavily debated in video game studies (cf. Consalvo, 2009; Zimmerman, 2012; Stenros, 2012), the debate is not as present in analog role-playing game studies. We suspect this is because the porousness between game and life has been acknowledged for some time, e.g., through the subcultural emphasis on research (Fine, 1983), social conflict and bleed affecting RPG communities (Bowman, 2013), the physical embodiment component feeling more life-like (Hugaas, 2019; Westborg, 2024), and the ritual aspects of role-play being reminiscent of psychomagical rituals themselves (Harviainen 2011; Bowman & Hugaas, 2021; Cazaneuve, 2021).

References

Aarebrot, E., & Nielsen, N. (2012). Prisoner for a day: Creating a game without winners. In M. E. Eckoff Andresen (Ed.), Playing the learning game: A practical introduction to educational roleplaying, (pp. 24-29). Oslo, Norway: Fantasiforbundet.

Arenas, D., L., Viduani, A., & Araujo, R. B. (2022). Therapeutic use of role-playing game (RPG) in mental health: A scoping review.” Simulation & Gaming (March 2022).

Baird, J. (2021). Role-playing the self: Trans self-expression, exploration, and embodiment in (live action) role-playing games. International Journal of Role-Playing 11: 94-113.

Baird, J. (2022). Learning about ourselves: Communicating, connecting and contemplating rans experience through play. Gamevironments 17: Special Issue “Social Justice.”

Baird, J., Bowman, S. L. (2022). The transformative potential of immersive experiences within role-playing communities. Revista de Estudos Universitário 48, 1-48.

Baird, J., Bowman, S. L., & Hugaas, K. H. (2022). Liminal intimacy: Role-playing games as catalysts for interpersonal growth and relating. In N. Koenig, N. Denk, A. Pfeiffer, & T. Wernbacher (Eds.), The magic of games (pp. 169-171). Edition Donau-Universität Krems.

Baird, J., Bowman, S. L., & Toft Thejls, K. T. (2023). Euphoria: Role-playing gender, magic, and the carnivalesque as emergent authenticity. Paper presented at Party!: The 19th Annual Tampere University Game Research Lab Spring Seminar. Tampere, Finland. May 4-5, 2023.

Baker, I. S., Turner, I. J., & Kotera, Y. (2022). Role-play games (RPGs) for mental health: (Why not?) roll for initiative. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction 11, 1-9.

Ball, G. (2022). A phenomenological inquiry into the therapeutic aspects of tabletop roleplaying games [Doctoral dissertation]. UWE Bristol

Baltic Warriors. (2015). The project. Balticwarriors.net. Retrieved August 29, 2024, from https://www.balticwarriors.net/aboutus

Balzac, S. R. (2011). The use of structured goal setting in simulation design. Journal of Interactive Drama (4)1, 51-58.

Barab, S. A., Gresalfi, M., & Ingram-Goble, A. (2010). Transformational play: Using games to position person, content, and context. Educational researcher, 39(7), 525-536.

Bartenstein, L. (2022). Larp in cognitive behavioral psychotherapy (CBT). Video poster presented at the Transformative Play Initiative Seminar 2022: Role-playing, Culture, and Heritage, October 20-21, 2022. Online.

Bartenstein, L. (2024, June). Live action role playing (larp) in cognitive behavioral psychotherapy: A case study. International Journal of Role-Playing 15, 92-126. https://doi.org/10.33063/ijrp.vi15.322

Bean, A., Daniel Jr., E.S., & Hays, S. A. (Eds.). (2020). Integrating geek culture into therapeutic practice: The clinician’s guide to geek therapy. Leyline Publishing, 2020.

Beltrán, W. “S.” (2012). Yearning for the hero within: Live action role-playing as engagement with mythical archetypes. In S. L. Bowman & A. Vanek (Eds.), Wyrd con companion book 2012 (pp. 89-96). Los Angeles, CA: Wyrd Con, 2012.

Beltrán, W. “S.” (2013). Shadow work: A Jungian perspective on the underside of live action role-play in the United States. In S. L. Bowman & A. Vanek (Eds.), Wyrd con companion book 2013 (pp. 94-101). Los Angeles, CA: Wyrd Con, 2013.

Bion, W. P. (1959). Experiences in groups. Tavistock, England: Tavistock Publications.

Bion, W. P. (2013). Attacks on linking. The Psychoanalytic Quarterly 82(2): 285-300.

Bjørkelo, K. A., & Jørgensen, K. (2018). The Asylum Seekers larp: The positive discomfort of transgressive Realism.” In Proceedings of Nordic DiGRA 2018.

Blumenthal, B., & Haspeslagh, P. (1994). Toward a definition of corporate transformation. MIT Sloan Management Review, 35(3), 101.

Bowman, S. L. (2010). The functions of role-playing games: How participants create community, solve problems, and explore identity. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc.

Bowman, S. L. (2013). Social conflict in role-playing communities: An exploratory qualitative study. International Journal of Role-Playing 4, 4-25.

Bowman, S. L. (2014). Educational live action role-playing games: A secondary literature review. In S. L. Bowman (Ed.), Wyrd con companion book 2014 (pp. 112-131). Los Angeles, CA: Wyrd Con.

Bowman, S. L, & Westborg, J. (In press for 2024 publication). Cheat sheet: What we can learn from eduLARP and other (non-TT-)RPGs.” In German: “Was wir von eduLARPs und anderen (Nicht-Tisch-)Rollenspielen lernen können.” In F. J. Robertz, & K. Fischer (Eds.), #eduRPG. Rollenspiel als methode der bildung. Gelsenkirchen: SystemMatters Publ.

Bowman, S. L., & Hugaas, K. H. (2019, December 10). Transformative role-play: Design, implementation, and integration. Nordiclarp.org. Retrieved August 29, 2024, from https://nordiclarp.org/2019/12/10/transformative-role-play-design-implementation-and-integration/

Bowman, S. L., & Hugaas, K. H. (2021). Magic is real: How role-playing can transform our identities, our communities, and our lives. In K. Kvittingen Djukastein, M. Irgens, N. Lipsyc, & L. K. Løveng Sunde (Eds.), Book of magic: Vibrant fragments of larp practices (pp. 52-74). Oslo, Norway: Knutepunkt.

Bowman, S. L., Torner, E., & White, W. J. (Eds.). (2016). International Journal of Role-playing 6, Special Issue: Role-playing and Simulation in Education 2016.

Bowman, S. L., Torner, E., & White, W. J. (Eds.). (2018). International Journal of Role-playing 8, Special Issue: Role-playing and Simulation in Education 2018.

Boyd, R. D., & Myers, J. G. (1988). Transformative education. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 7(4), 261-284.

Brauner, P., & Ziefle, M. (2022). Beyond playful learning – Serious games for the human-centric digital transformation of production and a design process model. Technology in Society, 71, 102140.

Bowman, S. L, Diakolambrianou, E., & Brind, S., eds. (In review). Transformative Role-playing Game Design. Transformative Play Research Series. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis, Uppsala University Publications.

Brown, M. (2017, December 1). Larp tools: Pronoun markers and correction mechanics techniques. Nordiclarp.org. Retrieved August 29, 2024, from https://nordiclarp.org/2017/12/01/larp-tools-pronoun-markers-correction-mechanics/

Brown, M. (2018). Post-play activities for larp: Methods and challenges. Analog Game Studies V(II) (June 2).

Burns, D. (2014). The therapy game: Nordic larp, psychotherapy, and player safety. In S. L. Bowman (Ed.), The wyrd con companion book 2014 (pp. 28-41). Los Angeles, CA: Wyrd Con.

Causo, F., & Quinlan, E. (2021, March 12). Defeating Dragons and Demons: Consumers’ perspectives on mental health recovery in role-playing games. Australian Psychologist.

Cazeneuve, A. (2018). How to queer up a larp: A larpwright’s guide to overthrowing the gender binary. In R. Bienia & G. Schlickmann (Eds.), LARP: Geschlechter(rollen): Aufsatzsammlung zum Mittelpunkt. Braunschweig, Germany: Zauberfeder Verlag.

Cazeneuve, A. (2021, Aug. 13). Larp as magical practice: Finding the power-from-within. Nordiclarp.org. Retrieved August 29, 2024, from https://nordiclarp.org/2021/08/13/15523/

Chen, S., & Michael, D. (2006). Serious games: Games that educate, train, and inform. Boston, MA: Thompson Course Technology.

Consalvo, M. (2009). There is no magic circle. Games and Culture, 4(4), 408-417. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412009343575

Connell, M. (2023). Tabletop role-playing therapy: A guide for the clinician game master. W. W. Norton & Company.

Crookall, D., Moseley, A., & Whitton, N. (2014). Engaging (in) gameplay and (in) debriefing. Simulation & Gaming, 45(4-5), 416-427.

Cullinan, M. (2024, June). Surveying the perspectives of middle and high school educators who use role-playing games as pedagogy. International Journal of Role-Playing 15 (June), 127-41. https://doi.org/10.33063/ijrp.vi15.335

Cullinan, M., & Genova, J. (2023). Gaming the systems: A component analysis framework for the classroom use of RPGs. International Journal of Role-Playing 13, 7-17.

Daniau, S. (2016). The transformative potential of role-playing games: From play skills to human skills. Simulation & Gaming 47(4): 423–444.

Dashiell, S. L. (2020). Hooligans at the table: The concept of male preserves in tabletop role-playing games. International Journal of Role-Playing 10, 26-39.

Deterding, S. (2018). Alibis for adult play: A Goffmanian account of escaping embarrassment in adult play. Games and Culture 13(3): 260-279.

Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R., & Nacke, L. (2011). From game design elements to gamefulness: Defining ‘gamification’. In Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference: 9–15.

Diakolambrianou, E. (2021). The psychotherapeutic magic of larp. In K. Kvittingen Djukastein, M. Irgens, N. Lipsyc, & L. K. Løveng Sunde (Eds.), Book of magic: Vibrant fragments of larp practices (pp. 95-113). Oslo, Norway: Knutepunkt.

Diakolambrianou, E., & Bowman, S. L. (2023). Dual consciousness: What psychology and counseling theories can teach and learn regarding identity and the role-playing game experience. Journal of Roleplaying Studies and STEAM 2(2): 5-37.

Edland, T. K., & Grasmo, H. (2021). From larp to book. In A. E. Groth, H. “H.” Grasmo, & T. K. Edland (Eds.), Just a Little Lovin’: The Larp Script. Drøbak.

Fantasiforbundet. (2014, August 3). A history of larp – Larpwriter Summer School 2014 [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rf_gej5Pxkg

Femia, G. (2023). Reparative play in Dungeons & Dragons.” International Journal of Role-Playing 13, 78-88.

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press.

Fey, J., Dagan, E., Segura, E. M., & Isbister, K. (2022). Anywear Academy: A larp-based camp to inspire computational interest in middle school girls. In Designing interactive systems conference (DIS ’22), June 13–17, 2022, Virtual Event, Australia. ACM, New York, NY, USA.

Games for Change. 2022. Initiatives. Gamesforchange.org. Retrieved August 29, 2024, from https://www.gamesforchange.org/initiatives/

Garcia, A. (2016). Teacher as dungeon master: Connected learning, democratic classrooms, and rolling for initiative. In A. Byers & F. Crocco (Eds.), The role-playing society: Essays on the cultural influence of RPGs. McFarland.

Geneuss, K. (2021). The use of the role-playing technique STARS in formal didactic contexts. International Journal of Role-Playing 11, 114-131.

Geneuss, K., Bruun, J., & Bo Nielsen, C. (2019, December 27). Overview of edu-Larp conference 2019. Nordiclarp.org. Retrieved August 29, 2024, from https://nordiclarp.org/2019/12/27/edu-larp-conference-2019/

Goffman, E. (1986). Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience. Boston, MA: Northeastern University Press.

Gong, C., & Ribiere, V. (2021). Developing a unified definition of digital transformation. Technovation, 102, 102217.

Groth, A. E, Grasmo, H. “H.,” & Edland, T. K. (2021). Just a little lovin’: The larp script. Drøbak.

Gutierrez, R. (2017). Therapy & dragons: A look into the possible applications of table top role playing games in therapy with adolescents [Master’s Thesis]. Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations 527: 1-39.

Gygax, Gary, and Dave Arneson. 1974. Dungeons & Dragons. TSR, Inc.

Halat Hisar. (2016). The basics. Nordicrpg.fi. Retrieved August 29, 2024, from https://www.nordicrpg.fi/halathisar/concept/

Hand, D. (2023). Role-Playing games in psychotherapy: A practitioner’s guide. Palgrave Macmillan.

Harder, Sanne. (2007). “Confessions of a Schoolteacher: Experiences with Role-playing in Education.” In J. Donnis, M. Gade, and L. Thorup (Eds.), Lifelike, 228-235. Copenhagen, Denmark: Projektgruppen KP07. http://nordiclarp.org/w/images/a/af/2007-Lifelike.pdf

Harder, S. (2018, March 28). Larp crush: The what, when and how. Nordiclarp.org. Retrieved August 29, 2024, from https://nordiclarp.org/2018/03/28/larp-crush-the-what-when-and-how/

Harviainen, J. T. 2011. The larping that is not larp. In T. D. Henriksen, C. Bierlich, K. F. Hansen, & V. Kølle, Think Larp: Academic Writings from KP2011. Copenhagen, Denmark: Rollespilsakademiet.

Harviainen, J. T. (2012). Ritualistic games, boundary control, and information uncertainty. Simulation & Gaming (43)4, 506-527.

Harviainen, J. T. (2014). From hobbyist theory to academic canon. In J. Back (Ed), The cutting edge of Nordic larp, (pp. 183-188). Denmark: Knutpunkt.

Henrich, S., & Worthington, R. (2021). Let your clients fight dragons: A rapid evidence assessment regarding the therapeutic utility of ‘Dungeons & Dragons’. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health 18(3), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/15401383.2021.1987367

Hoge, M. (2013). Experiential learning for youth through larps and RPGs. In S. L. Bowman & A. Vanek (Eds.), The wyrd con companion book 2013 (pp. 38-4). Los Angeles, CA: Wyrd Con.

Homann, J. (2020). Not only play: Experiences of playing a professor character at College of Wizardry with a professional background in teaching. International Journal of Role-Playing 10, 84-103.

Hoke, R., & Risk, J. (In press). Rewriting the rules: Game-based learning for affective and cognitive student engagement in an undergraduate history course. International Journal of Roleplaying 17.

Hugaas, K. H. (2019, January 25). Investigating types of bleed in larp: Emotional, procedural, and memetic. Nordiclarp.org. Retrieved August 29, 2024, from https://nordiclarp.org/2019/01/25/investigating-types-of-bleed-in-larp-emotional-procedural-and-memetic/

Hugaas, K. H. (2024). Bleed and identity: A conceptual model of bleed and how bleed-out from role-playing games can affect a player’s sense of self. International Journal of Role-Playing 15 (June), 9-35.

Huizinga, J. (1958). Homo ludens: A study of the play-element in culture. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Hyltoft, M. (2010). Four reasons why edu-larp works. In K. Dombrowski (ed.), LARP: Einblicke, 43-57. Braunschweig, Germany: Zauberfeder Ltd.

Illeris, K. (2006). When intended learning does not occur. Paper presented at the 36th Annual SCUTREA Conference, 4-6 July 2006, Trinity and All Saints College, Leeds.

Illeris, K. (2009). A comprehensive understanding of human learning. In Contemporary theories of learning: Learning theorists…In their own words. Routledge.

Illeris, K. (2013). Transformative learning and identity. Routledge.

Iuama, T. R, & Falcão, L. (2021). Analog role-playing game studies: A Brazilian overview. International Journal of Role-playing 12, 6-21.

Johansson, K., Robinson, R., Back, J., Bowman, S. L., Fey, J. Marquez-Segura, E., Waern, A., & Isbister, K. 2024. Why larp?! A synthesis paper on live action roleplay in relation to HCI research and rractice. ACM Transactions in Computer-Human Interaction (September 2024). https://doi.org/10.1145/3689045

Jones, K. C., Koulu, S., & Torner, E. (2016). Playing at work. In K. Kangas, M. Loponen, & J. Särkijärvi (Eds.), Larp politics: Systems, theory, and gender in action (pp. 125-134). Helsinki, Finland: Solmukohta 2016, Ropecon ry.

Jones, S. (Ed.). (2021). Watch us roll: Essays on actual play and performance in tabletop role-playing games. McFarland & Co.

Katō, K. (2019). Employing tabletop role-playing games (TRPGs) in social communication support measures for children and youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) in Japan: A hands-on report on the use of leisure activities. Japanese Journal of Analog Role-Playing Game Studies 0, 23-28.

Kemper, J. (2017, June 21). The battle of Primrose Park: Playing for emancipatory bleed in Fortune & Felicity. Nordiclarp.org. Retrieved August 29, 2024, from https://nordiclarp.org/2017/06/21/the-battle-of-primrose-park-playing-for-emancipatory-bleed-in-fortune-felicity/

Kemper, J. (2018, February 7). More than a seat at the feasting table. Nordiclarp.org. Retrieved August 29, 2024, from https://nordiclarp.org/2018/02/07/more-than-a-seat-at-the-feasting-table/

Kemper, J. (2020). Wyrding the self. In E. Saitta, J. Särkijärvi, J. Koljonen, A. S. Grove, P. Männistö (Eds.), What do we do when we play? Helsinki, Finland: Solmukohta.

Kemper, J., Saitta, E., & Koljonen, J. (2020). Steering for survival. In E. Saitta, J. Särkijärvi, J. Koljonen, A. S. Grove, P. Männistö (Eds.), What do we do when we play? Helsinki, Finland: Solmukohta.

Kessock, S. (2014). Cultural appropriation and larp. In J. Back (Ed.), The cutting edge of Nordic larp,125-134. Denmark: Knutpunkt.

Kilmer, E. D., Davis, A. D., Kilmer, J. N., & Johns, A. R. (2023). Therapeutically applied role-playing games: The game to grow method. Routledge.

Koljonen, Johanna. (2019). “An Introduction to Bespoke Design.” In J. Koljonen, J. Stenros, A. S. Grove, A. D. Skønsfjell, & E. Nilsen (Eds.), Larp Design: Creating Role-play Experiences (pp. 25-29). Copenhagen, Denmark: Landsforeningen Bifrost.

Koljonen, J. (2020). Larp safety design fundamentals. JARPS: Japanese Journal of Analog Role-playing Game Studies 1: Emotional and Psychological Safety in TRPGs and Larp (September 21): 3e-19e.

Koski, N. (2016). Not a real man? – Trans* politics in the Finnish larp scene. In K. Kangas, M. Loponen, and J. Särkijärvi (Eds.), Larp Politics: Systems, Theory, and Gender in Action, 136-143. Helsinki, Finland: Solmukohta 2016, Ropecon ry.

Lasley, J. (2021). Fantasy In real life: Making meaning from vicarious experiences with a tabletop RPG internet stream. International Journal of Role-Playing 11, 48-71.

Lederach, J. P. (2003). Conflict Transformation. Retrieved August, 29, 2024, from https://www.beyondintractability.org/essay/transformation

Lederach, J. P. (2014). Little book of conflict transformation: Clear articulation of the guiding principles by a pioneer in the field. New York: Good Books.

Lehto, Kerttu. (2024, June). Nordic larp as a method in mental health care and substance abuse work: Case SÄRÖT. International Journal of Role-Playing 15, 74-91. https://doi.org/10.33063/ijrp.vi15.326

Leonard, D. J., & Thurman, T. (2018). Bleed-out on the brain: The neuroscience of character-to-player. International Journal of Role-Playing 9, 9-15.

Leonard, D. J., Janjetovic, J., & Usman, M. (2021). Playing to experience marginalization: benefits and drawbacks of “dark tourism” in larp. International Journal of Role-Playing 11: 25-47.

Linnamäki, J. (formerly Pitkänen). (2019). Forms of change: How do psychodrama, sociodrama, playback theatre and educational live action roleplay (edularp) contribute to change.” La Hoja de Psicodrama 28(71) (May).

Living Games Conference. (2018, August 17). Immersive narratives, personas, and multi-intelligence scaffolding — Faros, Lux. YouTube.

MacDonald, J. (2022). Beyond cracking eggs. In J. Pettersson (Ed.), Distance of touch: The Knutpunkt 2022 magazine (pp. 51-54). Knutpunkt 2022 and Pohjoismaisen roolipelaamisen seura.

Magnussen, R., & Misfeldt, M. (2004). Player transformation of educational multiplayer games. In Proceedings of the Other Players conference. IT University of Copenhagen.

Mendez Hodes, J. (2019, February 14). “May I play a character from another race?”. Jamesmendezhodes.com. Retrieved August 29, 2024, from https://jamesmendezhodes.com/blog/2019/2/14/may-i-play-a-character-from-another-race

Montola, M. (2010). The positive negative experience in extreme role-playing. In Proceedings of DiGRA Nordic 2010: Experiencing games: Games, play, and players. Stockholm, Sweden, August 16.

Montola, M., Stenros, J., & Saitta, E. (2015, March 29). The art of steering: Bringing the player and the character back together. Nordiclarp.org. Retrieved August 29, 2024, from https://nordiclarp.org/2015/04/29/the-art-of-steering-bringing-the-player-and-the-character-back-together/

Moriarity, J. (2019, October 18). How my role-playing game character showed me I could be a woman: Being someone else gave me a glimpse of what life might be like if I lived it honestly as myself. The Washington Post.

Mortensen, T. E., & Jørgensen, K. (2020). The paradox of transgression in games. Routledge.

Nakamura, L. (1995). Race in/for cyberspace: Identity tourism and racial passing on the internet. Works and Days (13)1-2, 181-193.

New World Magischola. (2016, July 27). New World Magischola – Short documentary [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JgcEEQKzU-Q

Nordic Larp Talks. (2015, February 12). Making mandatory larps for non players – Miriam Lundqvist [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xnIKzQlnRuU

Nordic Larp Wiki. (2019, September 3). Playing to lose. Nordiclarp.org. Retrieved August 29, 2024, from https://nordiclarp.org/wiki/Playing_to_lose

Nordic Larp Wiki. (2022, August 15). Knutepunkt-books. Nordiclarp.org. Retrieved August 29, 2024, from https://nordiclarp.org/wiki/Knutepunkt-books

Nordic Larp Wiki. (2023, October 16). Edu-larp conferences. Nordiclarp.org. Retrieved August 29, 2024, from https://nordiclarp.org/wiki/Edu-larp_conferences

Pedersen, T. K. (2017, February 13). Tears and the new norm. Nordiclarp.org. Retrieved August 29, 2024, from https://nordiclarp.org/2017/02/13/tears-and-the-new-norm/.

Peterson, J. (2012). Playing at the world: A history of simulating wars, people and fantastic adventures, from chess to role-playing games. San Diego, CA: Unreason Press.

Plass, J. L., Mayer, R. E., & Homer, B. D. (Eds.). Handbook of game-based learning. MIT Press, 2020.

Reacting Consortium. (2024). I. Reactingconsortium.org. Retrieved August 29, 2024, from https://reactingconsortium.org/event-5355152

Reininghaus, G. (2019, June 14). A manifesto for LAOGs – Live action online games. Nordiclarp.org. Retrieved August 29, 2024, from https://nordiclarp.org/2019/06/14/a-manifesto-for-laogs-live-action-online-games/

Reynolds, S. K., & Germain, S. (2019). Consent in gaming. Seattle, WA: Monte Cook Games.

Role Simposio. 2024. Role: V Simpósio de RPG, Larp e Educação. Role Simposio.

Rusch, D. C. (2017). Making deep games: Designing games with meaning and purpose. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Salen, K., & Zimmerman, E. (2003). Rules of play: Game design fundamentals. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Semenov, A. (2010). Russian larp history: The view from Saint Petersburg. In E. Larsson (Ed.), Playing reality: Articles on live action role-playing (pp. 17-28). Interacting Arts.

Sidhu, P. & Carter, M. (2020). The critical role of media representations, reduced stigma and increased access in D&D’s resurgence. In Proceedings of DiGRA 2020, 1-20.

Solmukohta. 2024. Edularp conference Tampere 2024. Solmukohta.eu.

Sottile, Emry. 2024. “It might have a little to do with wish fulfillment”: The life-giving force of queer performance in TTRPG spaces. International Journal of Role-playing 15, 61–73. https://doi.org/10.33063/ijrp.vi15.324

Stenros, J. (2012). In defence of a magic circle: The social, mental and cultural boundaries of play. In R. Koskimaa, F. Mäyrä & J. Suominen (Eds.), DiGRA Nordic 2012 conference: Local and global – Games in culture and society, Tampere Finland, June 6-8, 2012.

Stenros, J. (2015). Playfulness, play, and games: A constructionist ludology approach [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Tampere.

Stenros, Jaakko, & Tanja Sihvonen. (2019, December 23). Queer while larping: Community, identity, and affective labor in Nordic live action role-playing.” Analog Game Studies: 2019 Role-Playing Game Summit.

Stenros, J., & Montola, M., (Eds.). (2010). Nordic larp. Stockholm, Sweden: Fëa Livia.

Tanenbaum, T. J., & Tanenbaum, K. (2015). Empathy and identity in digital games: Towards a new theory of transformative play. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games (FDG 2015), June 22-25.

Tanenbaum, T. J. (2022). Restorying trans game studies: Playing with memory, fiction, and magic as sites for transformative identity work. Keynote at Meaningful Play, East Lansing, MI, Oct. 12-14, 2022.

Torner, E. (2013). Transparency and safety in role-playing games. In S. L. Bowman & A. Vanek (Eds.), The Wyrd Con Companion Book 2013, pp. 14-17. Los Angeles, CA: Wyrd Con, 2013.

Torner, E. (2018). “Just a Little Lovin’ USA 2017.” In A. Waern & J. Axner, Shuffling the Deck: The Knutpunkt 2018 Color Printed Companion. ETC Press.

Trammell, A. (2023). Repairing play: A Black phenomenology. MIT Press.

Transformative Play Initiative. (2022a, March 9). Beyond the couch: Psychotherapy and live action role-playing – Elektra Diakolambrianou [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m03Q5K6dx3A

Transformative Play Initiative. (2022b, November 14). Designing the framing – – Josefin Westborg [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FCtpAYemJng

Transformative Play Initiative. (2022c, January 5). Introduction to Transformative Game Design – Sarah Lynne Bowman [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/mAQmZu7F9-g?si=1ujxg-cF9hYOxGxF

Transformative Play Initiative. (2022d, January 2). Transformative Game Design: A Theoretical Framework – – Sarah Lynne Bowman [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BX1U73eF53A

Transformative Play Initiative. (2024, February 23). Roleplaying with kids: Creating transformative experiences for Children under 12 – Angie Bandoesingh [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZaKfbadMYVU&t=1s

Turner, V. (1974). Liminal to liminoid in play, flow, and ritual: An essay in comparative symbology. Rice University Studies 60(3), 53-92.

van Gennep, A. (1960). The rites of passage. M. Vizedom & G. Caffee (Trans.). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Vi åker jeep -The Home of Jeepform. (2007). Bleed. Jeepen.org. Retrieved August 29, 2024, from https://jeepen.org/dict/

Waern, A. (2010). “I’m in love With someone that doesn’t exist!!” Bleed in the context of a computer game. In Proceedings of DiGRA Nordic 2010: Experiencing games: Games, play, and players. Stockholm, Sweden, August 16.

Walsh, O., & Linehan, C. (2024, June). Roll for insight: Understanding how the experience of playing Dungeons & Dragons impacts the mental health of an average player. International Journal of Role-Playing 15, 36-60. https://doi.org/10.33063/ijrp.vi15.321

Westborg, J. (2023). The educational role-playing game design matrix: Mapping design components onto types of education. International Journal of Role-playing 13, 18-30.

Westborg, J. (2024). Placing Edu-larp on the Map of Educational Learning Theories: A Critical Discourse Analysis of Ideas about Learning in the Edu-larp Community [Master’s Thesis]. Gothenburg University.

Westborg, J., & Bowman, S. L. (In press for 2024 publication). GM screen: The didactic potential of RPGs. In German: Das didaktische Potential von Rollenspielen. In F. J. Robertz & K. Fischer (Eds), #eduRPG. Rollenspiel als methode der bildung. Gelsenkirchen: SystemMatters Publ.

Westerling, A. (2013). Naming the middle child: Between larp and tabletop. In K. Jacobsen Meland & K. Øverlie Svela (Eds.), Crossing theoretical borders (pp. 17-28). Norway: Fantasiforbundet.

White, W. J. (2020). Tabletop RPG design in theory and practice at the Forge: Designs and discussions. Springer.

Winardy, G. C. B., & Septiana, E. (2023). Role, play, and games: Comparison between role-playing games and role-play in education. Social Sciences & Humanities Open 8, no. 1: 100527-. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2023.100527

Winnicott, D. W. (1960). The theory of the parent-infant relationship. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis 41, 585–595.

Winnicott, D. W. (1971). Transitional objects and transitional phenomena. Playing & reality. Tavistock, England: Tavistock Publications, 1971.

Yuliawati, L., Wardhani, P. A. P., & Ng, J. H. (2024). A scoping review of tabletop role-playing game (TTRPG) as psychological intervention: Potential benefits and future directions. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 17, 2885–2903. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S466664

Zalka, C. V. (2019). Forum-based role playing games as digital storytelling. McFarland Press.

Zimmerman, E. (2012, February 7). Jerked around by the magic circle – Clearing the air ten years later. Game Developer. Retrieved August 29, 2024, from https://www.gamedeveloper.com/design/jerked-around-by-the-magic-circle—clearing-the-air-ten-years-later

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.