Adam Jerrett (University of Portsmouth)

Abstract

This research investigates the creation of What We Take With Us (WWTWU), a semiautobiographical pervasive game designed to enhance wellbeing that applied research-through-design across the game lifecycle. WWTWU utilises both physical and digital spaces and interactions to engage players in a series of reflective activities. The research provides developer-focused insights into the holistic process of personal and serious game creation, from ideation to reportage, to highlight the benefits and drawbacks of game creation as reflective practice. The research highlights challenges such as terminological confusion in serious games, the impacts of solo development, and difficulties with player engagement in such games. The findings advocate for robust support systems for developers and emphasises the importance of utilising player-centric design principles in such games to increase community engagement and cultural relevance. The research therefore contributes to academic and practical understanding of the complexities involved in personal game creation while showcasing how they can be transformative for players and developers alike.

Introduction

Within the games industry, creative decisions are often explained in “postmortems” (Wawro, 2015). Within academia, similar process-based discussion is less common, as research typically prioritises the results of the game’s research studies. However, the creative process is increasingly described as inherently beneficial, especially for personal games (Danilovic, 2018; Rusch, 2017). Research-through-design (RtD) is a methodology well-suited for exploring process-based findings, as it reveals insights that creators can only discover through engagement with the creative process (Frayling, 1994). RtD is thus gaining popularity in game development research (Coulton & Hook, 2017; Phelps & Consalvo, 2020).

This research uses RtD to explore the creation of What We Take With Us (WWTWU), a wellbeing-focused pervasive game and commercial-grade output from a practice-based PhD project. It examines the knowledge generated from the holistic process of serious (Michael & Chen, 2005) and pervasive (Montola et al., 2009) game creation from ideation to reportage, thereby extending RtD beyond design to encompass the entire creative process.

WWTWU consists of various formats: a room game similar to an escape room, a Discord-based online alternate reality game (ARG), and web-based game with associated workshops. Players complete tasks that promote self-reflection and wellbeing. These tasks (e.g., listening to music, telling stories, and reflecting on emotions) can be completed without engaging in WWTWU’s wider narrative. This standalone, task-based design was inspired by the question-based design of You Feel Like Shit (Miklik & Harr, 2016). To augment the tasks and encourage communal participation, WWTWU’s narrative follows Ana Kirlitz, a fictional character navigating her wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Through her diary-style Discord server and the room game (her abandoned office), players uncover her story while undertaking their own wellbeing journeys by completing WWTWU’s tasks.

WWTWU was a personal game developed in response to the pandemic to address my own and others’ wellbeing struggles at the time (Razai et al., 2020). The project’s personal nature informed the RtD process, offering additional perspective and insights for creators embarking on similar projects. The research will examine each stage of WWTWU’s creative process (ideation, development, deployment, and reportage) to advance understanding around the process of serious/personal game creation. It highlights the potential challenges faced during the lifecycle of such projects post-pandemic, whilst showcasing their transformative impact.

Background

Personal game creation

Personal game creation provides an avenue for developers to reflect on and express their personal experiences. Aside from technical or artistic skill development, game development is increasingly seen as a vehicle for personal growth and reflection (Danilovic, 2018; Harrer, 2011; Rusch, 2017). By embedding their own experiences into games, developers can process complex lived experiences and potentially heal from unresolved trauma through the act of creation. This experience of processing through creative making is at the heart of “existential”, transformative game design practice, which utilises elements from psychotherapy to make creators sensitive to their existence. This is done by calling attention to their uniqueness, facilitating an understanding of values, and encouraging reflection on one’s past and future. In doing so, creators explore their inner selves through the design process, potentially resolving internal conflicts and impacting their real-life decisions and actions afterwards (Rusch, 2020). Values-conscious design (Flanagan & Nissenbaum, 2014) similarly utilises Schön’s (1983) reflective practice to better understand how personal values are embedded into games. In both cases, such deep reflection can foster beneficial, prosocial outcomes for developers (Danilovic, 2018). Elude (Rusch, 2012), represents an artefact from such existential game design practice by representing its creator’s personal struggles with depression.

Such personal games show developers and players with similar experiences that games are a valid medium for exploring such topics. For non-developer games researchers, understanding the potential of creation as cathartic breeds a deeper appreciation and understanding of games beyond their entertainment value while encouraging reflection on their own (potentially similar) positionality. Researchers can also better understand the benefits and possibilities of game creation by upskilling themselves through its practice (Harrer, 2011). Similarly, these games may foster a deeper appreciation of their craft in non-reflective game developers, potentially inspiring them to create their own personal games.

Personal game creation can also be useful for typically-marginalised developers, who can use it to express their lived experiences (Harrer, 2019). To this end, autobiographical game jams provide an educational opportunity for often-novice developers wanting to engage in personal game design practice, typically by emphasising narrative games based on developers’ lived experiences (Danilovic, 2018; Harrer, 2019). These events often use simple tools like Bitsy for game creation (Harrer, 2019). These collaborative environments provide a safe space for creators to explore their personal experiences, while also providing players with experiences that make them feel understood (Lawhead et al., 2019; Rusch, 2017). This merging of lived experience and gameplay is known as “design bleed” (Toft & Harrer, 2020). “Bleed” is a concept from Nordic larp that denotes the blurring of boundaries between character and player during roleplay (Stenros & Bowman, 2018). Design bleed expands bleed from the play into design and encourages designers to incorporate personal experiences into game design to explore topics often overlooked in the wider games industry. These meaning-making creative experiences are often referred to as “transformative” (Phelps & Rusch, 2020).

Creating transformative artefacts

Transformation in this context refers to a change in player understanding, the game’s systems or its context (Salen & Zimmerman, 2003). Transformative play can be further segmented into “explorative play”, when players test the boundaries of game systems to cause unexpected behaviour (Back et al., 2017); “creative play”, which allows players to create their own goals (Back et al., 2017); and “transgressive play”, where players deliberately violate game structures through cheating exploiting loopholes (Consalvo, 2009; Salen & Zimmerman, 2003). Within such contexts, game mechanics encourage strategic thinking by imposing limits on players, and provide roleplaying opportunities within an immersive environment that can engender empathy (Tanenbaum & Tanenbaum, 2015).

These understandings of transformative play suggest that explorations of a game’s mechanics can lead to emergent behaviours that provide player experiences outside the scope of traditional understandings of play and games. Challenging such notions is central to Malaby’s (2007) description of games as “contrived [contingencies] that generate interpretable outcomes”. In their view, games are inherently structured to allow for player agency, thereby encouraging meaningful engagement that changes players’ understanding of the game and/or themselves. Such engagement can lead to cognitive and emotional changes through greater understanding of situations, as advocated for by empathy games (Belman & Flanagan, 2010), or behavioural changes through persuasive games that change player behaviour by challenging it (Dansey, 2014). These transformations range from temporary behavioural change to profoundly and permanently affecting players’ identities and worldviews (Tanenbaum & Tanenbaum, 2015).

While transformative play can occur within any game, it can also be explicitly designed for. Culyba (2018) outlines eight elements to help define such transformations including defining the purpose, understanding the audience, determining desired transformations, identifying barriers, incorporating key concepts, leveraging expert resources, examining prior implementations, and devising impact assessments. This process is non-linear and flexible, allowing teams to adjust their approach as needed. However, Rusch (2020) argues that such frameworks discount subtler transformations that are not easily measurable. Reflective game design (Khaled, 2018) addresses this by creating games that focus on critical reflection, instead of concrete solutions, to challenge players’ assumptions. In these designs, perspective-taking provides explicit connections between in-game and real-world experiences and assists knowledge transfer (Schrier & Farber, 2017). Players must also maintain a critical self-awareness during play to actively engage in meaning-making, rather than getting absorbed in gameplay (Belman & Flanagan, 2010). These principles guided WWTWU’s creative process.

Research Methodology

Research-through-design (RtD) provides a framework for knowledge generation within practical human-computer interaction projects (Zimmerman et al., 2007). Inspired by Schön’s (1983) approaches to reflective practice, RtD posits that creation is a means of knowledge generation. It is being increasingly used within games research to explore the process of practice and creators’ subjective experience with their craft. The methodology has been used in the creation of design principles and best practices for commercial games (Howell, 2015); as a reflective process to aid iteration when creating games (Akmal & Coulton, 2019); and in educational contexts when teaching game development (Phelps & Consalvo, 2020). The methodology’s focus on subjective experience also aligns with postmodern research paradigms that embrace subjective experiences as vital within scholarly research – an approach Coulton and Hook (2017) advocate for within games research. Most importantly, RtD allows designers to uncover new approaches to and understanding of a craft that are only possible through engagement in creative practice (Frayling, 1994). In doing so, it effective bridges the gap between academic research and industrial practice, making it a suitable methodological approach for a commercial grade game-based practice research project.

This research utilizes RtD to examine the creation of WWTWU from its ideation to its reportage. By discussing each stage of the process, the research aims to reveal actionable insights for game developers and academics seeking to explore personal and serious game creation themselves.

The results of this research are framed in the first person, akin to autoethnographic research (Bochner & Ellis, 2016), though autoethnography is not fully utilised as the research does not centre the methodology’s cultural insights. The research also utilises reflexivity from autoethnography, given its similar importance in RtD. Reflexivity in autoethnography involves transparency in the methodological approach, openness about feelings regarding the research process and data, and acknowledgment of positionality (Brown, 2015). These elements are utilised due to WWTWU’s autobiographical nature and to aptly present the subjective journey of the RtD process.

By employing Fook’s (2018) reflective framework, I practiced such reflexivity by examining my positionality both before and after conducting the research. One assumption was my belief that others would share my vision of games as a prosocial force for good. This shaped the design philosophy of WWTWU and my expectations that participants would play it. I also reflected on my positionality as a cisgendered, heterosexual white male, how this might influence perceptions of my work, and the complexities it brought to my role as both a researcher and designer. I recognised that while I am invested in creating games for change, my identity, allyship, and validation were not predicated on WWTWU’s success as a game or research project. This openness increased my self-awareness throughout the research and allowed me to reconcile the research’s findings with my journey through a personal RtD process. As such, the research’s presentation is similar to industrial postmortems (Wawro, 2015).

The research question is: What personal and social insights for creators emerge from research-through-design when applying it to each stage of the creation of a personal game?

When examining this question, it is important to note that RtD processes differ amongst researchers and social contexts. This subjectivity is central to values-conscious design (Flanagan & Nissenbaum, 2014) and when considering games as social institutions (Obreja, 2023). Both game creation and gameplay are informed by personal and societal values in the culture in which they take place (Obreja, 2023). While I developed WWTWU as a solo creator, its philosophy and the resulting artefact were informed by my personal values that result from my societal and cultural upbringing (Flanagan & Nissenbaum, 2014). Similarly, players play WWTWU in concert with their own values and the community’s. Social understandings and values thus collectively shape a personal game’s creation and its reception.

Data collection utilised a research diary to practice reflexivity and provide insights into the creative process (Anderson, 2006). Play of WWTWU itself was also used as a reflective tool. Further, participant and non-participant observation (Pickard, 2013), individual player interviews, and focus groups (Foddy, 1994; Stewart & Shamdasani, 1990), were all used for gathering stakeholder data.

Reflexive thematic analysis was used to uncover pertinent insights for game creators (Braun & Clarke, 2021). Data was coded not through open coding (Saldana, 2021), but instead through critical incidents (i.e., notable events) – an approach sometimes used in grounded theory (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). These codes provided “data domains” (Braun & Clarke, 2019) which, after further development, were constructed into themes for each individual stage. The research presents the most prevalent theme from each stage in the Discussion section.

What We Take with Us Overview

Though this research focuses on insights from WWTWU’s creative process, the game’s unconventional nature and presentation contextualises its results and discussion. WWTWU emphasises “wellbeing” through values-conscious design, consisting of three parts: a physical room game, a Discord-based online ARG, and a website and associated workshops.

Mechanics

Initially conceptualised as an empathy-based escape room, WWTWU deviated from typical mechanics by eschewing timers and locked doors, only keeping the genre’s fixed location and narrative framing (Nicholson, 2015). The game mechanics presents a series of 11 tasks to a single player. These tasks were intentionally designed to be playable anywhere, allowing for both remote and location-based play. They were inspired by wellbeing practices, and included organising a workspace, acknowledging feelings, creating art, dancing, and telling stories, among others. The game’s tasks were presented on a website (Pötzsch, 2022), shown in Figure 1, accessible in both the room and the ARG.

Players utilise a Discord server to interact with the creator of the server, game protagonist Ana Kirlitz, who regularly shares ‘past playthroughs’ of the game that document her experiences from 2020 to 2023, and other players. Room players play WWTWU in Ana’s abandoned office in Portsmouth, UK, where they can additionally discover epistolary artefacts elaborating on her story.ù

Narrative

Ana Kirlitz relocates to Portsmouth in early 2020 after a breakup. The new environment allows her career and wellbeing to thrive, aided by her play of WWTWU’s tasks. However, COVID-19 lockdowns affect her mental health, and she struggles with anxiety and depression throughout the pandemic. In late 2021, her mother contracts COVID-19 and dies. Ana then returns to her childhood home to mourn and support her. She abandons her Portsmouth office (Figure 3).

While home, Ana continues playing WWTWU via the website, charting her experiences on the private Discord server she uses as a journal (Figure 2). Later, she makes the Discord public, hoping to build a game community for her fictitious PhD research. The ARG begins as players join the server, where they learn about Ana’s life during the pandemic. They accompany her on a journey of personal growth by completing and discussing the game’s tasks. She also grants a research assistant (me, the researcher) permission to have players play WWTWU in her abandoned office, which is the basis of the room game.

Game structure

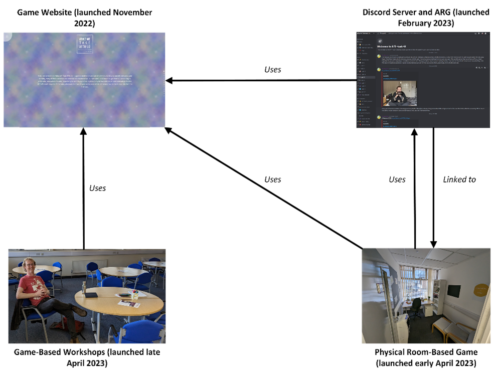

WWTWU comprises three components: a game website, a Discord-based ARG, and a physical room game. Both the ARG and room game highlight Ana’s story. As WWTWU’s tasks are mechanically separate from Ana’s story, standalone workshops using the website created a third game format, allowing additional data collection about the game mechanics beyond Ana’s narrative. Figure 4 illustrates the connections between these components.

Results

Ideation

As part of a PhD project, WWTWU’s creation began with a review of literature and practice in personal and serious game design. The project initially focused on empathy to enhance players’ emotional responses to difficult situations and encourage prosocial behaviour (Belman & Flanagan, 2010; Manney, 2008). Empathy-focused games are often described as “games for change”, given their social impact, and are supported by annual awards ceremonies and development initiatives (Games for Change, 2019).

For my “game for change” I aimed to create an empathy-focused escape room. This contrasted the genre’s typically systems-heavy approach (Nicholson, 2015). Escape rooms’ systemic focus (i.e., escaping the room) often overshadow its narrative, making it challenging to engender empathy in the format given empathy’s links to narrative (Blot, 2017).

However, further research showed that “empathy” can sometimes be reductive and appropriative, particularly when it accommodates a predominantly cisgender white male audience (Ruberg, 2020; Ruberg & Scully-Blaker, 2021). These critiques advocate for widening terminology around empathy, suggesting engagement with a game’s specific themes and values instead. This led to an exploration of broader related frameworks for values-conscious game design beyond mere empathy (see Belman & Flanagan, 2010; Flanagan, 2009; Gunraj et al., 2011; Harrer, 2019; Isbister, 2016; Schrier & Gibson, 2010; Sicart, 2011). This array of frameworks was utilised when creating design principles that guided WWTWU’s development ([author] et al., 2020, 2022; [author] & Howell, 2022).

Creation

My values of community, reflection, and music shaped WWTWU’s design philosophy and reflected the isolation I experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic. Development explored how these values affected wellbeing, the game’s central value. Community’s connection to wellbeing was highlighted during the pandemic due to the social isolation it caused (Razai et al., 2020). Music played a crucial role in civilian response to the pandemic (e.g., balcony concerts) (Cabedo-Mas et al., 2021), while also being a personal “asylum” for listeners (DeNora, 2016). Reflection was implemented in gameplay through “restorying” one’s experiences for personal growth (Kenyon & Randall, 1997). By encouraging players to articulate their lived experience, WWTWU aimed to transform players’ understandings of the pandemic. The game’s use of a website and Discord server similarly mirrored interactions with those mediums during it.

Ana’s narrative blended my and others’ experiences of the pandemic. However, developing her story was often overwhelming amidst the ongoing pandemic. Mental blocks and anxiety led to procrastination and lethargy. Remaining positive and focused, to effectively develop the game, was challenging. Such struggles showed how “design bleed” (Toft & Harrer, 2020), despite its potential benefits, uncovered difficult and unexpected emotions. While Ana’s narrative was authentic as a result, I often wondered at what cost. While “personal games” are often created by solo developers, the loneliness of the pandemic exacerbated the similarly solitary development process, emphasising the importance of support in such projects.

Deployment

WWTWU’s series of pervasive games was deployed and studied in real-time over three months in early 2023. The Discord ARG launched in February, with early marketing efforts targeting my personal and professional networks and attracting a small group of initial players. However, many of these had personal connections to me as the researcher. To mitigate participation bias and attract a broader, wellbeing-focused target audience, I advertised on Reddit’s r/ARG and r/SampleSize forums. I also pitched the game to journalistic publications and engaged the university’s marketing team.

These efforts fell flat – ignored by players and rejected for marketing due to the game’s niche audience, leaving me disheartened. This highlighted the importance of identifying and targeting player communities, even for personal games, during design and development. I naively believed if I built it, “they [would] come” (Robinson, 1989), which future creators should avoid. The ARG had 5 active players throughout its run. The room game, despite similar engagement strategies and a further incentive of a custom-made enamel pin, only garnered 7 participants. Though they thoroughly explored Ana’s office, they often overlooked important narrative elements and required frequent assistance which often broke immersion. Finally, the game-based workshops were also poorly attended, with 1, 2, and 4 players, respectively. Here, participants were often reluctant to share their personal experiences within a communal context, despite this being the purpose of the workshop. This shows that even willing participants may hesitate to discuss personal struggles, especially amongst strangers or in an explicit research context, making the outcomes of such games/research difficult to measure, as Rusch (2020) suggests.

Despite these challenges, there were some successes. The addition of new players towards the end of the ARG reinvigorated the Discord server, suggesting that with more time, the communal aspect of WWTWU could flourish. Similarly, workshop and room players appreciated how the game encouraged positive reflection, lifting their spirits and hinting at greater wellbeing and transformative potential with a larger audience.

Reportage

Though RtD primarily generates knowledge through creation and reflection, understanding artefact reception can enrich reflective findings by incorporating additional perspectives (Godin & Zahedi, 2014). This methodological ‘promiscuity’, incorporating both self-reflection and stakeholder feedback, allowed a comprehensive understanding of WWTWU’s impacts. WWTWU’s reportage process included surveys of various stakeholders including myself as designer through self-interview (Keightley et al., 2012), Ana’s actor as a “developer,” and players of each game format.

My experiences with WWTWU were deeply coloured by my inherent closeness to the project and my disappointment with its low participation. However, the game was broadly successful in its positive impacts on other stakeholders. Ana’s actor’s repeated engagement with the game and her character during development was so transformative that it inspired her to pursue a new career based on skills her grandfather taught her, subsequently obtaining a plastering qualification and starting her own business. This illustrates the profound effect of roleplay in pervasive games, aligning with Tanenbaum and Tanenbaum’s (2015) understanding of transformative play.

Beyond this significant result, players of various formats consistently identified and resonated with the core values of reflection, community, music, and wellbeing, showcasing the usefulness of values-conscious design. Specific findings include how WWTWU’s communal elements and use of music increased player wellbeing and reflection; how the experience of playing WWTWU in the workshops or room game was different than in players’ own spaces (which has implications for pervasive games’ physical designs and its effects on player comfort); and how differing levels of acceptance towards Ana as a character affected play, showcasing the importance of protagonists-by-proxy (Bonsignore, 2012) in pervasive games.

Most notably, WWTWU reshaped players’ perceptions of what games could be. By integrating real-world tasks within a game context, some players saw WWTWU as wellbeing tool rather than a traditional game, given WWTWU’s use of real-world wellness practices. Game elements like points and leaderboards were replaced with therapy-style questions, prompting players’ newfound understand of pervasive games and the wider potential of the games medium for personal growth. This perspective shift showcases how social understandings of games are guided by, and can redefined by play (Malaby, 2007; Obreja, 2023).

Discussion

Terminological Confusion in Serious Game Design

The research highlighted a significant issue in the realm of serious, values-conscious game design: confusion surrounding the terms “value” and “values”. In various fields, these terms have been applied when discussing the general usefulness of games (Lee et al., 2004), optimal outcomes in game theory (Elliott & Kalton, 1972), and, as applied here, abstract ideals in games. Furthermore, values-conscious design is often confused with values-driven design – a similar approach within engineering (Davis et al., 2022), leading to inconsistent communication across fields. Similarly, all values-conscious games are often categorised as “empathy games” (Ruberg, 2020), which can misrepresent other values embedded in such projects.

This terminological ambiguity poses challenges for both research and practice, as it obfuscates clarity regarding the intentions and outcomes of such values-conscious, serious games. Clarity is especially important within this domain, given the inherent subjectivity of players’ values and their interpretations of a game’s ones. While players, when asked about the game’s “themes”, identified WWTWU’s primary values, they also identified other potential values. I also used the term “themes”, instead of “values” when surveying players due to the term’s varying social interpretations. As such, more research and outreach should be done to unify vocabulary surrounding values in games (akin to empathy’s popularity). This research thus aligns with Flanagan and Nissenbaum (2014) in advocating for wider adoption of “values-conscious design” as a terminology and framework for personal or serious projects. Doing so allows for clearer communication of a game’s core values and message, enhancing coherence within games research, practice, and marketing contexts.

Personal Game Development as Laborious Process

WWTWU’s development highlighted the challenges of personal game creation, which often follows a designer-centric, auteur philosophy (Montola, 2012; Rusch, 2017). While integrating personal experiences into games through “design bleed” can create more authentic games (Toft & Harrer, 2020), the project revealed that this approach can also be labour-intensive and emotionally taxing, especially when undertaken in isolation during a global pandemic. As such, WWTWU’s creation challenged the idealised view of independent game development as a playful, liberating, and often successful creative process (Farmer, 2021). Its modest reception, despite positive feedback, felt like a failure, further amplifying my feelings of imposter syndrome, which are common within game development (Moss, 2016).

The findings highlighted the need for emotional and practical support systems to manage the psychological impacts on developers creating personal games, given its mental and technical difficulty. This could include community and wellbeing support, technical tutorials, or even ethical prerequisites for would-be developers, such as ensuring their high emotional resilience. While the integration of personal narratives in games can lead to authentic and meaningful creations for both creators and players, the potential psychological impacts of the topics being explored should not be ignored.

Post-Pandemic Community Engagement

WWTWU’s deployment revealed potential challenges for engaging communities in both pervasive games and research projects post-pandemic. While those who played were positive towards the game, many potential participants chose not to engage, often noting WWTWU was ‘not their type of game’ due to its emotional and personal gameplay. This presents a challenge for play research, given play’s voluntary nature (Suits, 2005), which may further be compounded by aversion to research participation (Patel et al., 2003). Player-centric design (Fullerton, 2008), as opposed to the designer-centric approach adopted with WWTWU, prioritises target audiences, and thus research participants, early in development, which may alleviate such issues.

Examining cultural factors that affect participation could provide additional insights. WWTWU’s room British players, for instance, were emotionally reserved, often not engaging on Discord during play. The South African ARG participants, by contrast, were more open, often sharing their own personal stories after seeing others doing so. These cultural nuances suggest that deploying WWTWU in different cultural contexts, like Nordic countries with strong pervasive game awareness, could yield significantly different results. As such, considering cultural ludoliteracies and expectations of identified target audiences is similarly paramount.

The game’s launch timing also played a role in its reception. Although WWTWU’s pandemic themes resonated with some players, some players specifically rejected the COVID-19 references. When one room game player noticed pandemic references in the room, they noted engaging less emotionally with those elements within the game. As such, WWTWU might have had a stronger impact if released during the pandemic’s height when these themes were more relevant. In a post-pandemic context, societal reintegration and shifting priorities have reduced interest in gaming (Gross, 2022), while digital fatigue has diminished engagement with once-vital platforms like Zoom and Discord (Anh et al., 2022). Moreover, the post-pandemic games industry faces broader challenges (e.g., developer layoffs, cost-of-living crises), which also affects player engagement. To combat this, creators should consider “long-tail” marketing strategies (Kanat et al., 2020) to ensure their games gain popularity over time, sustaining player engagement and community management through rapidly changing player needs and industry dynamics.

The Transformative Potential of Personal Games

WWTWU’s reception highlighted the differing experiences between creators and players in personal game projects. While as a designer I struggled through an emotional creative process and the disappointment of low participation, play experiences revealed the game’s true transformative potential.

Through play, WWTWU renewed my appreciation for music and deepened my understanding of my personal values. Moreover, playing what I had created reinforced my commitment to creating “games for change” While my guiding principle of focusing on the game’s impact on players rather than the external validation their opinions brought me often faltered throughout the journey, the multistage process of the project – from ideation to reportage – transformed my research and design thinking.

Ana’s actor similarly experienced a profound transformation: her roleplay led to transformative play (Tanenbaum & Tanenbaum, 2015) which she leveraged into a changed career trajectory. For others, WWTWU was a reflective tool that allowed them to identify their own values, and what mattered most to them. Community support through Discord, for example, was a defining characteristic for many players, transforming WWTWU’s initially solitary experience into a shared journey of growth, highlighting the importance of communities in such games. Player reactions to the physical play spaces of WWTWU similarly shows how their design can similarly transform players’ experiences, even when experiencing similar content.

Finally, in transforming traditional understandings of games and play through its unconventional presentation, WWTWU highlights the inherently social nature of play (Malaby, 2007; Obreja, 2023; Stenros, 2014), challenging “notgame” debates (Carle, 2015) and suggesting that pervasive games may be a pivotal genre in presenting agency-filled, real-world experiences rife for transformative play to players. However, given players’ misunderstandings of the genre within this project, effectively managing players expectations surrounding the nature, objectives, and scope of such transformative experiences remains important.

Conclusion

This research discussed the creative process of What We Take With Us, a semiautobiographical, wellbeing-focused, pervasive game, explored through a research-through-design methodology. It provided key insights for creators considering personal game development. It highlights challenges rarely addressed in the literature, including terminological confusion around “values”, the tolls of solo personal game development, and the impact of social outcomes like low post-launch engagement. Despite these challenges, WWTWU highlights the transformative potential of personal games for both players and creators. Findings suggest the need for robust support systems for those embarking upon such projects, and the importance of player-centric design for increasing community engagement and cultural relevance, while highlighting the cathartic potential of such projects.

Future research could include developing frameworks to provide practical and emotional support for personal game developers. Ethical considerations for such design should also be explored beyond advocacy. Furthermore, exploring the influence of player values on game participation explain player disengagement and highlight potential participation strategies. Finally, research examining individual and societal understandings of “play” and “game” may similarly increase engagement within personal games.

In conclusion, by examining my experience within the personal game development lifecycle, the research offers practical insights for academic and industrial contexts to support sustainable personal game creation, allowing the genre to not only transform their players, but their creators, too.

References

Akmal, H., & Coulton, P. (2019, April 11). Research Through Board Game Design. Proceedings of RTD 2019. Method & Critique – Frictions and Shifts in RtD, Delft and Rotterdam. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7855808.v1

Anderson, L. (2006). Analytic Autoethnography. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 35(4), 373–395. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891241605280449

Anh, L. E. T., Whelan, E., & Umair, A. (2022). ‘You’re still on mute’. A study of video conferencing fatigue during the COVID-19 pandemic from a technostress perspective. Behaviour & Information Technology, 42(11), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2022.2095304

Back, J., Segura, E. M., & Waern, A. (2017). Designing for Transformative Play. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 24(3), 18:1-18:28. https://doi.org/10.1145/3057921

Belman, J., & Flanagan, M. (2010). Designing games to foster empathy. International Journal of Cognitive Technology, 15(1), 5–15.

Blot, A. (2017). Exploring games to foster empathy [Masters Dissertation, Malmo University]. http://muep.mau.se/handle/2043/24479

Bochner, A., & Ellis, C. (2016). Evocative Autoethnography: Writing Lives and Telling Stories. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315545417

Bonsignore, E. (2012). The Birth of April G: Creating an ARG Protagonist-by-Proxy. In Rough Cuts: Media and Design in Process (1st ed.). The New Everyday.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern-based qualitative analytic approaches. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 21(1), 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12360

Brown, A. (2015). Awkward: The importance of reflexivity in using ethnographic methods. In Game Research Methods (pp. 77–92). ETC Press.

Cabedo-Mas, A., Arriaga-Sanz, C., & Moliner-Miravet, L. (2021). Uses and Perceptions of Music in Times of COVID-19: A Spanish Population Survey. Frontiers in Psychology, 11(1). https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.606180

Carle, D. (2015). A Game By Any Other Name: The “notgames” myth [Technology Blog]. The Skinny. https://www.theskinny.co.uk/tech/gaming/notgames-proteus-gone-home-dear-esther

Consalvo, M. (2009). Cheating – Gaining Advantage in Videogames. MIT Press.

Coulton, P., & Hook, A. (2017). Game Design Research through Game Design Practice. In P. Lankoski & J. Holopainen (Eds.), Game Design Research: An introduction to theory and practice (1st ed., pp. 169–202). ETC Press.

Culyba, S. (2018). The Transformational Framework: A Process Tool for the Development of Transformational Games. Carnegie Mellon University. https://doi.org/10.1184/R1/7130594.v1

Danilovic, S. (2018). Game Design Therapoetics: Autopathographical Game Authorship as Self-Care, Self-Understanding, and Therapy [PhD thesis, University of Toronto]. https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/handle/1807/89836

Dansey, N. (2014). Emergently-Persuasive Games: How Players of SF0 Persuade Themselves. In Cases on the Societal Effects of Persuasive Games (pp. 175–192). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-4666-6206-3.ch009

Davis, V., Davis, E., Lakin, J., & Marghitu, D. (2022, August 23). Framing Engineering as Community Activism for Values-Driven Engineering: RFE Design and Development (Years 3-4). 2022 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition. https://peer.asee.org/framing-engineering-as-community-activism-for-values-driven-engineering-rfe-design-and-development-years-3-4

DeNora, T. (2016). Music Asylums: Wellbeing Through Music in Everyday Life. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315596730

Elliott, R. J., & Kalton, N. J. (1972). The Existence of Value in Differential Games. American Mathematical Soc.

Farmer, C. (2021). Arrested (game) development: Labour and lifestyles of independent video game creators in Cape Town. Social Dynamics, 47(3), 455–471. https://doi.org/10.1080/02533952.2021.1999632

Flanagan, M. (2009). Critical Play: Radical Game Design (1st ed.). MIT Press. https://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2469995

Flanagan, M., & Nissenbaum, H. (2014). Values at Play in Digital Games. MIT Press.

Foddy, W. (1994). Constructing Questions for Interviews and Questionnaires: Theory and Practice in Social Research (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Fook, J. (2018). Reflective models and frameworks in practice. In C. Costley & J. Fulton (Eds.), Methodologies for Practice Research: Approaches for Professional Doctorates (1st ed., pp. 57–76). SAGE.

Frayling, C. (1994). Research in Art and Design. Royal College of Art Research Papers, 1(1), 1–5.

Fullerton, T. (2008). Game Design Workshop: A Playcentric Approach to Creating Innovative Games. CRC Press.

Games for Change. (2019). Home Page—Games For Change [Non-Profit Organisation]. Games for Change. http://www.gamesforchange.org/

Godin, D., & Zahedi, M. (2014). Aspects of Research through Design: A Literature Review. Design’s Big Debates – DRS International Conference 2014. DRS International Conference 2014, Sweden.

Gross, A. (2022, August 14). Gaming tapers off post-pandemic as players return to the real world. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/3e04a454-470e-490b-af87-bf65c435525c

Gunraj, A., Ruiz, S., York, A., Schrier, K., & Gibson, D. (2011). Power to the People: Anti-Oppressive Game Design. In Designing Games for Ethics: Models, Techniques and Frameworks (1st ed., pp. 253–274). Information Science Reference. https://www.igi-global.com/chapter/power-people-anti-oppressive-game/50743

Harrer, S. (2011). Game Design for Cultural Studies: An Experiential Approach to Critical Thinking. Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Games + Learning + Society Conference, 97–101. http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2206376.2206388

Harrer, S. (2019). Radical Jamming: Sketching Radical Design Principles for Game Creation Workshops. Proceedings of the International Conference on Game Jams, Hackathons and Game Creation Events 2019, 7, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1145/3316287.3316297

Howell, P. (2015). Disruptive game design: A commercial design and development methodology for supporting player cognitive engagement in digital games [Doctoral Thesis]. University of Portsmouth.

Isbister, K. (2016). How Games Move Us: Emotion by Design (1st edition). The MIT Press.

Jerrett, A. (2022). What We Take With Us (Version 1) [Browser]. Two Left. https://whatwetakewith.us/

Jerrett, A., Howell, P., & Dansey, N. (2020). Creating Meaningful Games through Values-Centred Design Principles. Proceedings of the Digital Games Research Association Conference 2020 Conference: Play Everywhere. DiGRA 2020: Play Everwhere, Tampere, FL. http://www.digra.org/wp-content/uploads/digital-library/DiGRA_2020_paper_66.pdf

Jerrett, A., Howell, P., & de Beer, K. (2022). Practical Considerations for Values-Conscious Pervasive Games. Proceedings of the Digital Games Research Association Conference 2022 Conference: Bringing Worlds Together. DiGRA 2022: Bringing Worlds Together, Krakow, PL. http://www.digra.org/wp-content/uploads/digital-library/DiGRA_2022_paper_80.pdf

Jerrett, A., & Howell, P. M. (2022). Values throughout the Game Space. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 6(CHI PLAY), 257:1-257:27. https://doi.org/10.1145/3549520

Kanat, I., Raghu, T. S., & Vinzé, A. (2020). Heads or Tails? Network Effects on Game Purchase Behavior in The Long Tail Market. Information Systems Frontiers, 22(4), 803–814. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-018-9888-x

Keightley, E., Pickering, M., & Allett, N. (2012). The self-interview: A new method in social science research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 15(6), 507–521. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2011.632155

Kenyon, G. M., & Randall, W. L. (1997). Restorying Our Lives: Personal Growth Through Autobiographical Reflection. Greenwood Publishing Group.

Khaled, R. (2018). Questions Over Answers: Reflective Game Design. In D. Cermak-Sassenrath (Ed.), Playful Disruption of Digital Media (pp. 3–27). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-1891-6_1

Lawhead, N., Sui, J., Snow, P., Snow, K., Hsia, J. J., & Freeman, N. (Directors). (2019). Personal Experiences as Games [Presentation]. Game Developers Conference. https://www.gdcvault.com/play/1025675/Personal-Experiences-as

Lee, J., Luchini, K., Michael, B., Norris, C., & Soloway, E. (2004). More than just fun and games: Assessing the value of educational video games in the classroom. CHI ’04 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1375–1378. https://doi.org/10.1145/985921.986068

Malaby, T. M. (2007). Beyond Play: A New Approach to Games—Thomas M. Malaby, 2007. Games and Culture, 2(2), 95–113.

Manney, P. J. (2008). Empathy in the Time of Technology: How Storytelling is the Key to Empathy. Journal of Evolution & Technology, 19(1), 51–61.

Michael, D. R., & Chen, S. L. (2005). Serious Games: Games That Educate, Train, and Inform (1st ed.). Muska & Lipman.

Miklik, A., & Harr, J. (2016). You Feel Like Shit [PC]. Amanda Miklik Coaching + Consulting.

Montola, M. (2012). Social Constructionism and Ludology: Implications for the Study of Games. Simulation & Gaming, 43(3), 300–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878111422111

Montola, M., Stenros, J., & Waern, A. (2009). Pervasive Games: Theory and Design. Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc.

Moss, R. (2016, January 22). Imposter syndrome: Game developers who feel like frauds. Polygon. https://www.polygon.com/features/2016/1/22/10776792/imposter-syndrome-game-developers-who-feel-like-frauds

Nicholson, S. (2015). Peeking Behind the Locked Door: A Survey of Escape Room Facilities. http://scottnicholson.com/pubs/erfacwhite.pdf

Obreja, D. M. (2023). Video Games as Social Institutions. Games and Culture, 15554120231177479. https://doi.org/10.1177/15554120231177479

Patel, M. X., Doku, V., & Tennakoon, L. (2003). Challenges in recruitment of research participants. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 9(3), 229–238. https://doi.org/10.1192/apt.9.3.229

Phelps, A., & Consalvo, M. (2020). Teaching Students How to Make Games for Research-Creation/Meaningful Impact: (Is Hard). International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1145/3402942.3402990

Phelps, A., & Rusch, D. C. (2020). Navigating Existential, Transformative Game Design. Proceedings of DiGRA 2020 Conference: Play Everywhere. DiGRA 2020: Play Everywhere, Tampere, FL.

Pickard, A. J. (2013). Research methods in information. Facet.

Razai, M. S., Oakeshott, P., Kankam, H., Galea, S., & Stokes-Lampard, H. (2020). Mitigating the psychological effects of social isolation during the covid-19 pandemic. BMJ, 369. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1904

Robinson, P. A. (Director). (1989). Field of Dreams [Drama]. Universal Pictures.

Ruberg, B. (2020). Empathy and Its Alternatives: Deconstructing the Rhetoric of “Empathy” in Video Games. Communication, Culture and Critique, 13(1), 54–71. https://doi.org/10.1093/ccc/tcz044

Ruberg, B., & Scully-Blaker, R. (2021). Making players care: The ambivalent cultural politics of care and video games. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 24(4), 655–672. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877920950323

Rusch, D. (2012). “Elude”: Designing depression. Proceedings of the International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games, 254–257. https://doi.org/10.1145/2282338.2282389

Rusch, D. (2017). Making Deep Games: Designing Games with Meaning and Purpose (1st edition). Routledge.

Rusch, D. (2020). Existential, transformative game design. JGSS, 2, 1–39.

Saldana, J. (2021). The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers (Fourth edition). SAGE Publications Ltd.

Salen, K., & Zimmerman, E. (2003). Rules of play: Game design fundamentals. MIT Press.

Schön, D. A. (1983). The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315237473

Schrier, K., & Farber, M. (2017). The Limits and Strengths of Digital Games as Empathy Machines (Working Paper 5; MGIEP Working Paper, pp. 1–35). Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Education. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000261993

Schrier, K., & Gibson, D. (Eds.). (2010). Designing Games for Ethics: Models, Techniques and Frameworks (1st edition). IGI Global.

Sicart, M. (2011). The Ethics of Computer Games (1st ed.). MIT Press.

Stenros, J. (2014). In Defence of a Magic Circle: The Social, Mental and Cultural Boundaries of Play. Transactions of the Digital Games Research Association, 1(2). https://doi.org/10.26503/todigra.v1i2.10

Stenros, J., & Bowman, S. L. (2018). Transgressive Role-Play. In Role-Playing Game Studies (pp. 411–424). Routledge.

Stewart, D. W., & Shamdasani, P. N. (1990). Focus groups: Theory and practice (1st ed.). Sage Publications.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. M. (1998). Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. SAGE Publications.

Suits, B. (2005). The Grasshopper: Games, Life and Utopia. Broadview Press.

Tanenbaum, T. J., & Tanenbaum, K. (2015). Empathy and Identity in Digital Games: Towards a New Theory of Transformative Play. FDG.

Toft, I., & Harrer, S. (2020). Design Bleed: A Standpoint Methodology for Game Design. http://www.digra.org/wp-content/uploads/digital-library/DiGRA_2020_paper_320.pdf

Wawro, A. (2015, March 13). 10 seminal game postmortems every developer should read [Games Industry Blog]. Game Developer. https://www.gamedeveloper.com/audio/10-seminal-game-postmortems-every-developer-should-read

Zimmerman, J., Forlizzi, J., & Evenson, S. (2007). Research through design as a method for interaction design research in HCI. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems – CHI ’07, 493–502. https://doi.org/10.1145/1240624.1240704

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.