Rob Gallagher (King’s College London)

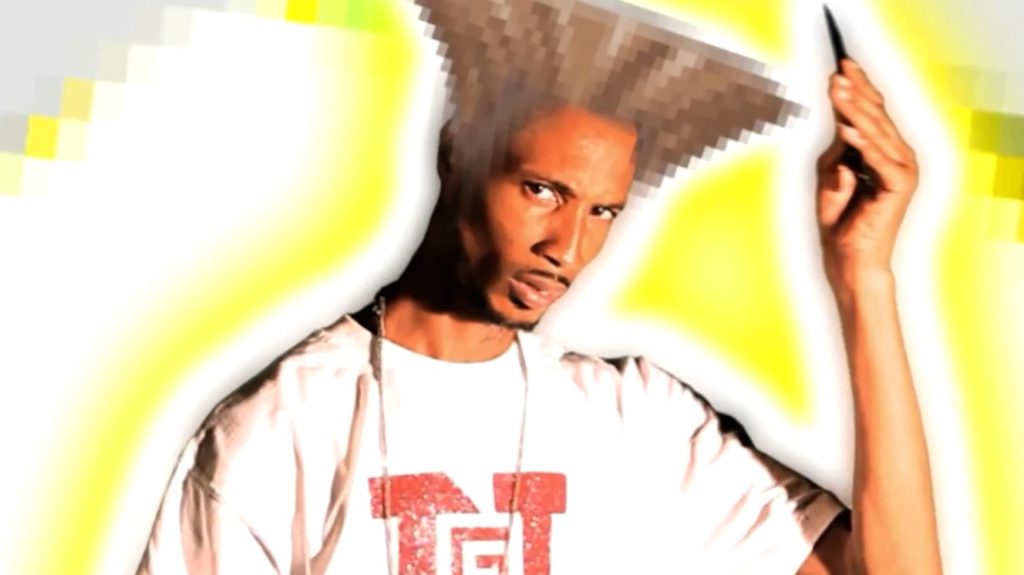

Cover image: D Double E in the video for “Street Fighter Riddim” (timandbarrytv, 2010)

Abstract

A fusion of jungle, garage, hip-hop and Jamaican sound system culture, grime emerged from the housing estates of East London in the early 2000s. The genre has always had strong ties to gaming, from producers who cut their compositional teeth on Mario Paint (Nintendo R&D1, 1992) to MCs who incorporate videogame references into their lyrics, album titles and aliases. This article traces grime’s relationship with gaming from the genre’s inception to the present, focusing on two case studies: veteran London MC D Double E’s 2010 track “Street Fighter Riddim” and Senegalese-Kuwaiti musician Fatima Al Qadiri’s 2012 Desert Strike EP, a “soundtrack” to her experiences of the first Gulf War. Showing how players build videogames into their life stories and identities, these case studies affirm that gaming was never the exclusive preserve of “nerdy” white middle-class males while foregrounding the ludic dimensions of digital musicianship and the musical dimensions of digital play.

KEYWORDS: Grime, identity, masculinities, sampling, gamer culture

Introduction

A startling new form of bass music characterized by manic energy, angular futurism and seething machismo, grime emerged from the council estates of East London in the early 2000s (Hancox, 2013, p.7). Rooted in jungle, garage, hip-hop and Jamaican sound system culture, the genre also had another key influence: videogames. This article argues that attending to the traffic between grime music and gaming culture can help us to understand better how players integrate gaming into their routines, relationships, biographies, vocabularies and identities, and to account for the diverse cultural functions videogames perform for different audiences in different contexts. This argument is developed in relation to two case studies: veteran London MC D Double E’s 2010 track “Street Fighter Riddim”, which uses characters from Capcom’s fighting game series as material for a playful musical self-portrait, and Senegalese-Kuwaiti musician Fatima Al Qadiri’s 2012 Desert Strike EP, a grime-inflected, videogame-referencing exploration of its creator’s childhood experiences of the first Gulf War.

Treating games as a musical and cultural resource, grime artists affirm James Newman’s (2008) argument that playing videogames is only one mode of playing with videogames. Newman, however, elaborates this claim in relation to the activities of “dedicated gamers” and “communities of fans” whose deep investments find expression in practices like fan-art, cosplay, speedrunning, glitch hunting and the production of online guides (ibid. p.13) 1. Unlike these practices, grime engages with videogames without being exclusively or even primarily “about” gaming. Like the hip-hop stars discussed by Nassim Balestrini (2015), grime artists incorporate a diverse array of verbal, visual and sonic materials into “’hybrid… works” of “intermedial life writing” 2 in which self-presentation shades into “myth-making” (pp.226 and 237). While many have looked to games for sounds, aliases and imagery, their productions and performances also bear the stamp of many other influences. Grime is a spur to recognize that individuals who may not fit conceptions of a “typical gamer”, and who would not necessarily see themselves as part of “gamer culture”, also participate in forms of creative play with videogames. The genre’s pioneers were mostly young black men living in some of the UK’s most deprived boroughs, some first- or second-generation immigrants. Their engagements with videogames affirm the importance of interrogating “the male (white and middle-class) image of the digital game player” and of expanding our conception of “gamer culture” (Shaw 2014, p.viii). Beyond that, looking at gaming through the prism of grime provides a new perspective on questions that have long preoccupied game studies scholars. Like gaming culture, grime poses a challenge to conventional understandings of creativity and cultural value. Both have been characterized as insular, all-male scenes oriented around troublingly violent, bafflingly repetitious cultural artefacts rife with second-hand signifiers and abrasive digital textures that are an affront to refined aesthetic sensibilities. While such complaints are hardly without foundation, they fail to tell the whole story.

While many have looked to games for sounds, aliases and imagery, their productions and performances also bear the stamp of many other influences. Grime is a spur to recognize that individuals who may not fit conceptions of a “typical gamer”, and who would not necessarily see themselves as part of “gamer culture”, also participate in forms of creative play with videogames.

This article attempts to offer a more even-handed account. The following section provides information on grime and its history while looking at how videogames have been incorporated into grime artists’ lyrics and music. It proposes that the frequency with which MCs and producers have turned to videogames for similes and samples points to a profound connection between gaming and grime, both of which are founded on the live configuration of libraries of fragments. Highlighting stories of producers whose first experiments with musical composition happened on gaming hardware, I argue that grime’s ongoing love affair with videogames brings both the ludic dimensions of digital musicianship and the musical dimensions of digital play into focus. This claim is developed in the next section through a close analysis of “Street Fighter Riddim”; serving as an example of how grime MCs articulate identities using videogame references, the track is also striking for what it suggests about the terms on which players can be said to identify with their avatars. The article concludes with a consideration of Desert Strike; drawing attention to the terms on which images, events, texts and styles circulate in an era of globalized markets and digital mediation, Al Qadiri’s EP has sparked discussions of authenticity, appropriation and gatekeeping that are relevant not just for game studies but for our understanding of networked cultural identities more generally.

Back in the Day: Grime, Tradition and Nostalgia

For Simon Reynolds (2007), grime represents a particular phase in the history of the “hardcore continuum”–a British rave music aesthetic encompassing forms like jungle, drum ’n’ bass, UK garage, 2-step, grime, dubstep and UK funky (p.351). Writing in 2002 of the sound that would become known as grime, Reynolds reads it as a “drastic remasculinization” of UK break-beat and bass music, exchanging the “bump ’n’ flex, the sexy swing” of 2-step garage for twitchy percussion, bludgeoning bass and furious rhymes (ibid. p.347). In emphasizing the role of MCs, grime continued a trend started by garage crews like Pay as U Go Cartel, from whose ranks grime lynchpins like Wiley, Flow Dan and DJ Slimzee emerged. But where garage lyrics were rife with aspirational hedonism (all fast cars, fur coats and freely flowing champagne) early grime tracks were altogether bleaker in tone, alternating between “alpha-male predatory” boasts and sketches of everyday struggle and stress (ibid.). Discussing poverty and crime while referencing soap operas, sitcoms and premiership football, early grime also witnessed gaming’s role in day-to-day urban life. Just as mid-90s US hip-hop crews like the Wu-Tang Clan and the Three Six Mafia peppered their work with references to wuxia cinema, Marvel comics and video nasties, so grime MCs drew images and aliases from games, whether it be Fudaguy comparing himself to a “shadow demon” from Shinobi (Sega, 1987-2011), Tinchy Stryder cribbing his name from a Capcom game or Footsie asserting “They’re not on it / They don’t want it / Watch how I make a boy / Run like Sonic” (Newham Generals, 2006). Providing grist for threats and power fantasies, games also offered a way to evoke the past. In some tracks, referencing gaming history becomes a means of asserting seniority; witness Demon (2005) declaring himself “old school like a Commodore 64” or Wiley (2006) boasting he “had the first Sega” on “Crash Bandicoot Freestyle”. In others, it is a means of conveying the nostalgia for “the idealised prelapsarian bliss of childhood” that Hancox (2013, p.26) sees as a key characteristic of grime. By incorporating verbal or aural references to cute characters (like Mario, Sonic, Spyro or Crash Bandicoot) into music full of rage and paranoia, grime artists create moments of tonal dissonance and sonic anachronism, speaking to a sense of lost innocence by framing themselves as children whose circumstances forced them to grow up too fast. For a genre bent on presenting itself as sonically forward thinking (one of the club nights that hosted grime was called FWD>>), grime’s gaming tastes can be strikingly retro, with producers remaining loyal to 8- and 16-bit sounds––see Royal-T’s “1UP” (2009), D.O.K’s “Chemical Planet” (2010) or Champion’s “Bowser’s Castle” (2013). Evocative of the 1980s and 1990s, when many of grime’s first wave were still at school, these references also correspond to geographic and socioeconomic factors, from the European success of Sega’s Mega Drive hardware (rebranded under the name Genesis in the US) to the tendency for “economically disadvantaged” gamers to play their games on consoles rather than PCs at this time (Taylor, 2012, p.130).

grime artists create moments of tonal dissonance and sonic anachronism, speaking to a sense of lost innocence by framing themselves as children whose circumstances forced them to grow up too fast

Even when grime tracks do not directly sample videogames, the crude tools used to create those formative early beats, many of which are awash with sawtooth waveforms and synthetic timbres, give them a sonic texture that will feel familiar to gamers. For this reason, grime is often discussed in relation to “chipmusic” 3. But where much chipmusic involves the recuperation of aspects of “geek” and/or “gamer” culture, which once carried negative associations of social ineptitude and sexual inadequacy, grime artists, by and large, are interested neither in challenging the idea of “nerds” as “losers and loners” nor in interrogating “the compulsory cool of black culture” (Newman, 2008, p.17; Eglash, 2002, p.58). The whole point of white nerdcore hip-hop artist Professor Shyguy’s 2013 album of chiptune R’n’ B covers is the ostensible incompatibility of the gamer stereotype with the ghetto lothario stereotype; for grime artists, though, there is nothing contradictory about incorporating videogame references into hypermasculine brags. When Skepta (2006) warns “I know skeng man in my postcode / That will sniff two lines and go into devilish mode / Shoot you in the face then skid round the corner like Yoshi and Toad” his yoking of cokeheads and killers to Super Mario Kart’s (Nintendo EAD, 1992) cartoon dinosaurs and anthropomorphic mushrooms is meant to affirm his status as a “badman” so blasé about murder that it might as well be a child’s game. Which is not to say that this persona is any more or less of a performance than Shyguy’s; as Hancox (2013) puts it, “even the youngest of grime fans” understand that most “skeng talk”4 is just that: talk (p.28).

As this suggests, grime is more reflexive than it is sometimes given credit for. That said, it is also a culture founded on “clashes” that see rival MCs trading insults, threats and occasionally blows, and agonistic machismo is very much its stock in trade. It shouldn’t surprise us, then, that grime is particularly fond of fighting games. On the first Lord of the Mics DVD (2004), a key window on early grime culture, head-to-head clashes are preceded by samples of Street Fighter II’s (Capcom, 1991) announcer yelling “FIGHT”. In 2013, when Bless Beats started a trend for uploading “war dubs” aimed at rival producers to the audio streaming site Soundcloud, meanwhile, peers responded with tracks sampling Mortal Kombat (Midway, 1992), Killer Instinct (Rare, 1994) and Tekken (Namco, 1994), tipping their hats to classics like JME’s (2005) “Baraka” and Dizzee Rascal’s (2004) ‘“Street Fighter”. Skepta and Smasher are among the many MCs to wax nostalgic about Street Fighter while, as discussed later, D Double E has oriented an entire track around Super Street Fighter IV (Capcom, 2010) similes. Perhaps most striking, though, is DJ Logan Sama’s story. Having transitioned from pirate radio to nationwide broadcasters like Kiss FM and BBC 1Xtra, he has, in recent years, become increasingly involved with fighting game culture, appearing on streams and podcasts, presenting a documentary on Street Fighter’s history and hosting events for Capcom at which grime artists often compete. That the two scenes are compatible is neither particularly shocking nor necessarily flattering: both thrive on macho taunts and fierce competition, and if fighting game culture still has issues with inclusivity and abuse, grime is no less prone than dancehall or hip-hop to homophobia and misogyny (Harper, 2014, p.124-5). Without wishing to discount these cultural politics, though, I want to argue that this crossover speaks to other, arguably more profound, parallels between grime and gaming.

Perfect Combos: Performance and Emergence

Paul Ward (2002) observes that all videogames entail “the combination of pre-rendered animated fragments” from a “finite library” of possible selections (p.126). Expert play is about demonstrating one’s mastery of this library by fluently stringing together fragments into sequences tailored to the situation at hand. Viewed as a configurative practice, gameplay betrays striking affinities with grime, affinities highlighted by stories of producers cutting their compositional teeth on games or gaming hardware: Ruff Sqwad’s Dirty Danger ran Fruity Loops on a PC his dad gave him for gaming, brothers JME and Skepta began making music on games like Mario Paint (Nintendo, 1992) and Music 2000 (Jester Interactive, 1999), and others have similar tales (Hancox, 2012; Twells, 2016). Even when grime producers weren’t using these tools 5, they were building beats according to rigid compositional rules. Characterized by eight bar loops, a tempo of around 140 beats per minute and an emphasis on bass, grime’s sound was shaped by the presets, patches and samples built into certain keyboards and software studios. Wiley’s influential early tracks, for example, use the “Gliding Squares” preset found on the Korg Triton, the same keyboard hailed in the title of the 2015 King Triton LP by Slew Dem’s JT the Goon. If grime tunes can sound formulaic and repetitious to the uninitiated, this is in part because each track has to play by these formal rules in order to suit the needs of DJs and MCs–MCs who, rather than fitting their lyrics to fit a particular track, will develop an arsenal of all-purpose rhymes ready to be deployed whenever the microphone comes their way, dividing their flows into 8- or 16-bar chunks. Like computer scientists, then, grime artists think in powers of two: “eights… sixteens, thirty-twos, sixty-fours” (Wiley, 2013). And, like game design, grime production is about constructing tightly circumscribed “possibility spaces” within which playful performances can occur (Salen & Zimmerman, 2004, p.390). Grime performers dexterously retrieve and recombine musical and lyrical fragments to create compelling new combos, competing for supremacy. While grime may be fiercely anti-authoritarian, it also understands that there can be no play without rules.

This playful attitude also informs grime artists’ use of “canned” sounds and familiar samples. In many electronic music genres, producers try to transform off-the-shelf sounds beyond recognition, creating new effects and obfuscating their sources. For Tricia Rose (1994, p.73), it was hip-hop that first “inverted this logic” by using recognizable samples, a practice that Tara Rodgers (2003) reads as a means of weaving a “complex web of historical references” while also “contesting dominant systems of intellectual property and musical ownership” (p.314). It is not necessarily incorrect to see grime’s use of ready-made sounds as betraying a lack of expertise, resources or patience–as Dizzee Rascal asks, “why spend a day on one tune when you can do four?” (Hancox, 2013, p.38). In the genre’s early years, in particular, many producers were resourcefully making use of what they had to hand. XTC’s 2004 track “Functions on the Low”, now best known as the basis for Stormzy’s UK top 10 hit “Shut Up” (StormzyTV, 2015), uses a stock Shakuhachi flute sample that has also featured in 1980s adult contemporary hits, Hollywood fantasy soundtracks and vaporwave satires (Howe, 2013). The demonic cackle that would become Terror Danjah’s personal sonic signature, meanwhile, came from a jungle sample pack (Ryce, 2010). But convenience and lack of access to technology are not the only reasons for using generic or second-hand sounds. As we have seen in relation to their use of samples from games, grime producers often deploy familiar sonic fragments to mobilize the meanings and associations they carry. Beyond that, using the same palette as other producers enables grime artists to situate themselves within an evolving aesthetic tradition. In some cases, they might be paying tribute to a hero: Wiley’s “eski click” effect (which fans speculate originated as a Mario sample) has spawned its own microgenre of “eski-beat” homages. In other cases, it can be a matter of contesting rival’s claim to a sound: Wiley himself made “Morgue” (2003) after a falling out with Wonder, using the same sonic building blocks as Wonder’s “What” (2003) in an attempt to beat his former crewmate at his own game. In both cases there is a lusory instinct in evidence, as producers compete to make familiar sounds their own, imbuing them with new resonance and significance.

One of the other elements that makes grime sound videogame-like is its use of sampled sound effects as melodic and percussive elements. Hearing producers Rapid and Dirty Danger weaving the same canned dog barks, gunshots, squealing tires, grunts and yells into new compositional patterns across the Ruff Sqwad compilation White Label Classics (2012) is not unlike watching, or listening to, a gamer working through a game’s grammar of available “moves” (jump, grab, shoot etc.) as they figure out how to progress. While rhythm games like Guitar Hero (Harmonix, 2005) foreground the parallels between musical performance and digital play, Kirkpatrick (2011) has argued that digital games in general have less in common with film or literature than they do dance, music and visual art. For him games are first and foremost about the dexterous production of harmonious forms and the interplay of repetitious patterns, not storytelling or symbolism. Kirkpatrick also observes that forms like dance have traditionally been gendered feminine, and it is perhaps this that has inspired videogame designers to (over)compensate by cloaking the process of “dancing with [our] hands” in bombastically masculine trappings, as a matter of lone starship pilots saving the galaxy or crack soldiers slaughtering terrorists (ibid. pp.153-4)6. In grime, too, brilliant displays of dexterity, fluency and formal imagination often come wrapped up in violent, misogynistic and homophobic imagery, as MCs bid to “merk” (murder) the beat, the dance, their rivals. Such rhetoric confronts critics with a quandary familiar to game studies scholars: how do we talk about the value of cultural forms whose representational content might be juvenile, generic, alienating or otherwise offensive? In evaluating these products can we separate form from content, and if so should we? I will return to this question later, arguing that while we should not let questions of content blind us to what is happening at a formal and an affective level, nor should we turn a blind eye to the way that grime and gaming perpetuate toxic stereotypes. For now, though, I want to pursue the idea that gaming and grime share an interest in live performance as a driver of emergence, an occasion for the playful production of new and unexpected combinations from familiar sets of parts.

As videogame preservationists note, games make little sense until they are played (Guins, 2014, p.31). Similarly, it can be hard to appreciate individual grime instrumentals until we have heard how DJs and MCs integrate them into the pirate radio sets that are the scene’s definitive documents. More than just a mode of dissemination, the limitations and affordances of pirate radio had a profound influence on grime’s sound. No sponsors to thank meant space for long-form mixes, liveness increased the stakes for performers and allowed for a degree of listener interaction, while FM radio’s poor sound quality fostered forms of sonic branding that ensured particular artists’ voices and styles would cut through the static. For producers, this meant aural watermarks like Terror Danjah’s cackling goblin; for MCs it meant developing and deploying catchphrases, nicknames and vocal tics that might be compared to fighting game “special moves”–not least when, christening himself the “E3 tiger” in a guttural growl that is part Southern rap, part Street Fighter’s Sagat performing a “tiger uppercut”, Wiley threatens to “Kill ‘em with the tiger / Triple-hit combos / 20-hit combos / Uppercuts, body blows” (Mak 10 et al, 2003). David Surman describes the special move as a “reward spectacle”: pulling off a tricky command at just the right moment, the Street Fighter player experiences “the visceral pleasure of synchronicity between play and representation… player and… player-character” (2007, p.210). The power of such reward spectacles is captured in a YouTube video cited by Todd Harper, in which famed Street Fighter player Daigo Umehara snatches victory from the jaws of defeat by parrying his opponent’s “super art” before responding with his own devastating combo to end the match (NightmareZer0, 2006). Conceding that “the video might be hard to understand if you don’t know the intricacies of the [gameplay] system”, Harper argues that “the crowd reaction… gives even the lay viewer a taste of just how incredible that moment was” (2014, p.2). Beyond that, it suggests how fighting games are engineered to generate emergent drama, and evokes those moments of synergy and serendipity that sometimes occur in grime sets as an MC spitting with dazzling pace and fluency deploys a particular bar just as the DJ is transitioning from one track into another. And, just as many fighting games feature replays, allowing players to review and savor the winning blow, grime has “rewinds”– a performative convention borrowed from the reggae sound system practice of abruptly breaking the flow of the mix and manually winding the record back to the start in recognition of a particular beat, bar or drop’s impact. Grime can, then, be viewed as a rule-bound framework within which performers deploy sonic signature moves to create moments of confluence and emergence, moments that are somehow more than the sum of their constituent parts. Like the Twitch streamers7, speedrunners, tournament competitors and professional gamers who wring catharsis, comedy and suspense from familiar rules, animations, joystick prompts and lines of code, grime artists compete to create definitive combos, staking a claim to owning a moment, a sound, a track.

“Just Like Dhalsim”, or Identification and Its Discontents

In the pursuit of such peak moments, DJs and MCs sometimes impose additional constraints on themselves, akin to the “expansive gameplay” practices of gamers who devise new “house rules”, game types or challenges (Parker, 2008). Such practices are attaining a higher profile within gaming culture, as online streamers seek to woo viewers with evermore demanding and outlandish displays of gaming skill; grime has long been using radio and YouTube in this way. For example, in a 2007 freestyle video, Tinchy Stryder spits as he drives (timandbarrytv, 2007), while on a 2008 Rinse FM show DJ Spyro (who repeatedly emphasizes that he is mixing without headphones) blends a snatch of Sonic the Hedgehog 2’s (Sega, 1992) soundtrack into the mix before dissolving into triumphant laughter (D.O.K would later sample the same track on ‘Chemical Planet’). MCs achieve similar effects through what literary scholars would call “procedural or constrained writing” (Baetens, 2012, 115-116). For the avant-garde OuLiPo group this meant projects like George Perec’s La Dispotion (1969), a novel in which the letter “e” never occurs; for a grime artist, “constrained writing” might entail composing verses that pun on multiple car marques or cigarette brands. So-called “alphabet bars”, which must incorporate all twenty-six letter sounds in sequence, offer another popular format for rule-bound rhyme composition. Some MCs are more adept at such wordplay than others. JME is particularly fond of writing lyrics that depend on double meanings, extended metaphors and the slipperiness of slang for their impact. In “Deceived” (2006a), for example, he sketches what sounds like a scene of gang violence (frayed tempers, knives and “tools”, blood) before revealing he’s actually describing one of the least grimy scenarios imaginable: doing some home improvement as a birthday surprise for his mum. In “Deadout” (2006b), meanwhile, he tells us he’s “mastered the levels” and that “all the other players want to look at my pad”, before specifying that he’s talking about notepads not joypads, “the music game” not “Super Mario”.

If “Deadout” frames lyrical composition as a form of play, the parallels are still clearer in D Double E’s “Street Fighter Riddim”, which name-checks most of the male characters in Super Street Fighter IV. Using these figures as lyrical avatars, the track suggests how grime might help game studies to rethink the player/avatar relationship. This relationship has, long preoccupied scholars. Decades ago, Marsha Kinder observed that her children were picking characters in Super Mario Bros. 2 (Nintendo R&D4, 1988) based not on how those characters looked or who they were diegetically, but on what they allowed the player to actually do in-game (1991, p.107). In recent years Adrienne Shaw (2014) has been particularly forthright in questioning “common sense logics of representation” and received ideas about identification (p.ix). For her,

“players do not automatically take on the role of characters/avatars. Playing as a character that is ostensibly ‘other’ to you (in terms of gender, race, or sexuality) is not necessarily transgressive or perspective-altering. Playing as a character that is like you (in terms of demographic categories) does not necessarily engender identification” (Shaw 2012, p.12).

Calling for greater nuance in discussions of diversity and representation, Shaw suggests that scholars should treat media as “source material for what might be possible, how identities might be constructed”, observing that she herself ‘grew up taking what I could from media and my surroundings, even when they didn’t represent me” (2014, pp.3, viii). Viewed as source material for identity work, Street Fighter is simultaneously rich and potentially treacherous; as Harper observes, its characters may be “colourful, brassy and unique”, but they are also crude “cultural and ethnic stereotypes” (2014, pp.1 and 109––original spelling). With “Street Fighter Riddim” D Double E makes these caricatures his avatars in a game of comic myth-making that, for all its flippancy, raises some interesting questions about the terms on which players relate to in-game characters. When, for example Double, a dark-skinned Londoner, “nearly six feet tall, but weighing only 130 pounds” with “elegant cut-glass features that border on emaciated” (Reynolds, 2007, p.379), aligns himself with Street Fighter’s Rufus, an obese American martial artist with a blonde braid, it is clearly not on the basis of nationality, ethnicity or outward appearance. Instead he uses the character to figure hunger or drive, declaring he wants to get paid so he can have a “big belly like Rufus” in a simile all the more arresting for the traits they don’t share. Throughout the lyric, and indeed the accompanying video (timandbarrytv, 2010), Double elicits laughter through dissonance, incongruity and bathos, foregrounding the ways in which he is both like and unlike Capcom’s world warriors. Ostensibly, the track is about the gap between reality and play, as Double affirms his authenticity by repeatedly declaring “it’s not a game like Street Fighter IV”. His lyrics, however, playfully breach this boundary while also defying demographic pigeonholes. Double might sound deadly serious when tells us he’s a “soldier like Guile”, but it’s hard to keep a straight face when Guile’s blocky wedge of blonde hair is transposed onto his head in the video; if Double’s “eyes are red like Akuma”, meanwhile, it’s not because they’re radiant with demonic energy but because he’s such a heavy “weed consumer”. Comedy often emerges from the gulf between grime’s world of drugs, criminality and cockney slang and Street Fighter’s cartoonish universe. Double uses rhyme and repetition to bridge this gulf, declaring he’s “shocking MCs like Blanka” before dubbing his rival “a wanker” and then threatening to “come through in a beat up Honda / And give man a hundred slaps like E. Honda”. In other cases comparisons are underwritten by puns and slang––as a lyricist he’s got “hooks like Balrog” (a boxer) and “spit[s] fire” like Dhalsim, a character whose special moves literally set his opponents alight. Double also finds room to showcase his command of gaming trivia: asserting “In the final fight / I’m the guy / Everyone wants to be my Cody”, he shows he’s aware that the characters Cody and Guy first appeared in Capcom’s Final Fight (1989), sneaking geeky insider knowledge into music that otherwise paints him as the very embodiment of myths of ghetto masculinity.

These myths are no less reductive than the national stereotypes on which Street Fighter II’s character designers drew. And while Double’s reiteration of well-worn tough guy tropes is knowing and often hilarious, “Street Fighter Riddim” ultimately does little to expand the claustrophobically narrow range of masculinities sanctioned in grime. The lyric does, however, have some intriguing implications for debates about avatars, identity and identification. Double uses Capcom’s characters to portray himself as witty, dangerous, mercurial, tenacious, resourceful, canny and, most of all, protean. In so doing, he offers us material with which to challenge the still-pervasive assumption that onscreen characters need to have key demographic variables in common with the player/viewer in order to be relatable. True, Double ignores Street Fighter’s female characters, but he also ignores Dudley, a black Londoner. Whether or not this relates to Dudley’s design (a dandified horticulturalist with an immaculately waxed moustache, Dudley is hardly the grimiest character in the game’s roster), it certainly suggests something other than classical “identification” is at work in “Street Fighter Riddim”. That something, I would argue, is closer to Carol Vernallis’ (2013, pp. 158-9) account of how music videos can foster rapport across ethnic and socioeconomic lines via “kinesthetic expansion and contraction, a dynamic sense of embodiment” that “through the process of entrainment” connects “my body, the performer’s body, and the music coursing through both”. Vernallis, here, echoes both Surman’s description of the reward spectacle and Brian Moriarty’s (2002) influential discussion of gaming and entrainment. Such texts suggest that while, in many cases, representation and narration play an important role in fostering player/avatar connections, these are neither the only, nor necessarily the primary, means through which such connections are forged. In other instances (and especially in the case of genres like the fighting game, where fast-paced action typically takes priority over storytelling and character development) it may be kinemes, contours, trajectories, cadences, rhythms or colors that do the lion’s share of the work. As Surman argues, the act of executing a special move at just the right moment can evoke a profound sense of being connected to our onscreen character, however irrational or fleeting this sense may be––just as vocal idiosyncrasies and technical flourishes (like the stutters, gurgles, groans and coos with which Double decorates his bars) can engage listeners viscerally quite apart from questions of lyrical content. Also important here is the track’s dependence on simile, the basic building block of grime lyricism. Where metaphor conflates tenor and vehicle, simile (often described as metaphor’s “weaker” cousin) concedes that the things it invokes are different even as it proposes that they have certain characteristics in common. Describing correspondences that are provisional, partial or temporary, simile arguably provides a better model than metaphor for describing what it is like to engage with an avatar. It also gives a better sense of how subjects perform identities online by configuring cultural fragments into new compositions which speak to them and which they can speak through, if only for the moment. Less a searching autobiographical meditation than a succession of pithy comparisons, witty punchlines and bravura acts of impersonation, “Street Fighter Riddim” exemplifies the playful, integrally intermedial character of contemporary life writing.

“Are You Really from the Ends?” Crossing the Borders of Grime and Gaming

Senegalese-Kuwaiti artist Fatima Al Qadiri’s 2012 EP Desert Strike also takes up questions of grime, gaming, autobiography and identification, albeit from another angle. There are no lyrics here, and no direct samples of the 1992 Electronic Arts shooter after which the record is titled. Rather, Al Qadiri describes this suite of instrumental tracks “inspired by grime” as a “soundtrack” for a traumatic passage in both her own life and the history of Kuwait (Dummy 2012). As the biographical sketch on her record label’s site has it,

“In 1992, ten-year-old Fatima Al Qadiri bought a copy of Desert Strike: Return to the Gulf, a top-down shooter game for Sega Megadrive based on Operation Desert Storm. A year prior, Kuwait’s inhabitants had experienced the apocalyptic vision of aerial bombings, air raid sirens, and skies filled with smoke from black oil fires. Time collapsed, schools closed, Fatima and her sister, Monira, spent their entire time at play – and began an addiction to video games that lasted for several years” (Fade to Mind, 2012).

Desert Strike, then, is about appropriation: commemorating Saddam Hussein’s murderous land-grab and the USA’s military reprisal, it also references Electronic Arts’ appropriation of this scenario as material for a game––and it does so by borrowing from grime, a genre that caught Al Qadiri’s ear partly through its use of videogame samples. In interviews she describes grime as “the most macho genre of western music… martial! The most apocalyptic and the most childlike music”, observing that, “as a child who’d lived through the apocalypse, it resonated with me” (Sandhu, 2014). She also notes that “as a videogame fan, I knew some of the earliest grime tracks were recorded using PlayStations”, suggesting that by combining “video game FX” which sound “innocent in isolation” with “warring beats and bass” grime producers fashioned a uniquely potent mode of expressing of anger, dread and trauma (Sandhu, 2014; Dummy, 2012). Originally a vehicle for everyday experiences of crime and violence on London’s estates, Al Qadiri found in grime a sonic vocabulary equally suited to conveying the experience of living in a literal warzone: “I don’t think anyone has really encapsulated that sensation… in a more accurate way than those tunes from the early 2000s” (ibid.).

In discussing Desert Strike, Al Qadiri also reveals a keen awareness of globalized capital’s cultural crosscurrents. Reminiscing about a childhood spent watching “Chinese and Japanese cartoons” alongside British sitcoms, she explains that “like the majority of middle-class Kuwaitis, I’d go to London every summer… go to Woolworths to buy candy and comic books”. Indeed, she first learned of Kuwait’s invasion when she “woke to watch a Japanese cartoon dubbed into Arabic” only to find a newsreel playing (ibid.; Sandhu 2014). Professing her love for the music of games like Castlevania (Konami, 1986), she describes Desert Strike (the game) as featuring “one of the ugliest video game soundtracks I’ve ever come across” (Dummy, 2012). It is this “ugliness” (the aesthetic ugliness of the game’s “shrill, high-pitched, really unsettling” sonics and the ethical ugliness of its “disturbing” repackaging of a war she actually lived through) that seems to license Al Qadiri’s appropriation of Desert Strike’s title for a record of her own music informed by her own memories of the conflict (ibid.).

Dummy’s interviewer implicitly frames this act of appropriation as an instance of what postcolonial theorists have called “writing back”, whereby colonized authors respond to and rework imperialist “pre-texts” to tell their own stories (Dummy, 2012; Thieme, 2001, pp. 2-3). When it comes to Al Qadiri’s relationship with Electronic Arts, this model makes sense. It has its limits as a framework for understanding her relationship with grime, however. For where writing back tends to be understood in terms of a disempowered colonial periphery and an empowered imperialist center, it is harder to discern who wields power when it comes to Al Qadiri’s repurposing of musical conventions developed by pioneering grime artists. The same can be said of early grime’s much-discussed fascination with “oriental” tunings and textures. To be sure, “sinogrime”8 tracks like Jammer’s “Thug” (2004) smack of “sonic colonialism, whereby aural fragments are used for perceived “exotic” effect, without investment in, or engagement with, the music culture from which the sample was gathered” (Rose, 2003, p.318). Equally, though, they might be said to signal an outward-looking “cosmopolitan disposition” akin to that of certain “Western players of Japanese videogames” (Consalvo, 2012, p.200). Sinogrime is hardly a matter of a colonizing center’s cultural elite romanticizing a “primitive” subaltern tradition; Hancox (2013, pp. 29-30) interprets tracks like “Thug” as expressing grime’s futurism and its “aspirational, acquisitional tendencies”, evoking “Shanghai tower blocks and the millennial promise of the newest superpower” in order to express an “intuition about where the future lies, geopolitically” on the part of British subjects disillusioned with what post-imperial, post-industrial Britain has to offer them.

Grime’s sonic evocations of “the mysterious East”, in short, are every bit as complex as Al Qadiri’s evocation of early 21st century East London, reflecting the vicissitudes of a globalized popular culture in which sorting centers from peripheries, the over- from the under-privileged is not so easy as it once might have been. A mixed-race woman, raised in a war-torn country, Al Qadiri is also a graduate of New York University, child of diplomats and artists. Does her engagement with grime express as a sense of solidarity or identification with black British teenagers on Blair-era council estates? Is it appropriative or exoticizing? How do we map the power differentials and the dynamics of identification in such a case?

Conclusion

In the beginning, “grime was not just local but microscopically local”, an “intensely territorial” scene rooted in “postcode wars and inter-estate beefs”, proliferating via acetate dubplates and white label records, FM broadcasts, cassette tapes and Nokia phones (Hancox, 2013, pp. 39-41; Reynolds, 2007, p. 380). Over time, file sharing, video streaming, and social media have brought the sound to audiences from other geographical locations and other cultural and socioeconomic “positions”––listeners like me, a white, middle-class British male who started downloading grime sets as a university student in the mid-2000s. Even as the internet has expanded and diversified grime’s listenership, however, it has also enabled the kinds of abusive gatekeeping gestures to which Al Qadiri alludes: “internet trolls have told me that I don’t make grime” (Dummy, 2012). Like gamergate’s harassment of perceived threats to “gamer culture”9, such gestures prove it is easier to bully scapegoats than to engage thoughtfully with the myriad forces shaping popular culture in our networked and globalized age.

But if I am dubious of bids to paint Desert Strike as ersatz or illegitimate to shore up an image of what grime used to be or ought to be, I am equally suspicious of another mode of narrating the relationship between the two––one that will ring bells with videogame scholars. For, implicit in some accounts of Desert Strike is a kind of redemption narrative, whereby a genre that was, in the hands of the young men first drawn to it, a violent, juvenile plaything, realizes its potential as a “serious” artform, the vehicle for an autobiographical trauma narrative that echoes scholarly critiques of the “military-entertainment complex” (De Peuter & Dyer-Witheford, 2009, p.101). This is the way that gamification and “serious games” are sometimes framed: as a matter of a medium considered trivial at best and pernicious at worst finally being turned to a worthwhile purpose. There are parallels, too, with the denigration of the tastes and habits of so-called “bro gamers” by middle-class gaming journalists (Baxter-Webb, 2016), and with the advent of what Felan Parker calls “prestige games”, titles that purport to transcend “mere entertainment”, often by subverting the conventions of familiar genres like the 2D platformer or the first-person shooter to expressive ends (Parker, 2015, p.2) 10.

The music of figures like D Double E and Al Qadiri resoundingly affirms that gamer culture was never the exclusive preserve of “nerdy” white middle-class males, while also underscoring the playfulness of electronic music and the musicality of digital play. In grime as in gaming culture, rule-bound frameworks and libraries of component parts become the basis for compelling acts of live, configurative performance, blurring the line between identity work and intermedial play.

One might use the term “prestige grime” to describe the recent spate of melancholy, meditative album-length deconstructions of grime by artists like Al Qadiri, Sd Laika, Logos or Visionist. Formally reflexive, conceptually sophisticated and tonally cogent, these works lend themselves more readily to critical analysis and exegesis than, say, D Double E’s scattershot back catalogue––a back catalogue that, like the fighting games it occasionally references, is also rife with violent and, as anyone who has heard Newham Generals’ 2009 “Bell Dem Slags” can attest, sexist imagery. As cultural critics, we should not ignore this, but nor should we use it as an excuse to dismiss forms like grime or fighting games out of hand, as an alibi for resorting to politically inert formalist analyses, or as a cue to focus only on works that bend popular forms into more prestigious, or less problematic, shapes. For while grime’s relationship with gaming emphasizes how rife with tired myths of masculine potency both remain, this is not all it tells us. The music of figures like D Double E and Al Qadiri resoundingly affirms that gamer culture was never the exclusive preserve of “nerdy” white middle-class males, while also underscoring the playfulness of electronic music and the musicality of digital play. In grime as in gaming culture, rule-bound frameworks and libraries of component parts become the basis for compelling acts of live, configurative performance, blurring the line between identity work and intermedial play.

References

Baetens, J. (2012). OuLiPo and proceduralism. In J. Bray, A. Gibbons & B. McHale (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to Experimental Literature New York: Routledge, pp.115-127..

Balestrini, N. (2015). Strategic Visuals in Hip-Hop Life Writing. Popular Music and Society, 38(2), pp.224-242.

Baxter-Webb, J. (2016). Divergent masculinities in contemporary videogame culture: a tale of geeks and bros. In L. Joyce and B. Quinn (Eds.), Mapping the Digital: Cultures and Territories of Play. Oxford: Inter-Disciplinary Press,.

Berlatsky, N. (2014, October 22). The Art War before Gamergate. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2014/10/gamergate-and-comics/381686/

Braddock, K. (2004, February 22). Partners in Grime. The Independent. Retrieved from http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/music/features/partners-in-grime-5355390.html

Carlsson, A. (2008). Chip music: low-tech data music sharing. In K. Collins (Ed.), From Pac-Man to Pop Music Interactive Audio in Games and New Media. Aldershot: Ashgate, pp. 153-162.

Chess, S. & Shaw, A. (2015). A Conspiracy of Fishes, or, How We Learned to Stop Worrying about #GamerGate and Embrace Hegemonic Masculinity. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 59(1), pp. 208-220.

Consalvo, M. (2012). Cosmo-play: Japanese videogames and western gamers. In D.G. Embrick, J.W. Talmadge & A. Lukacs (Eds.), Social Exclusion, Power, and Video Game Play: New Research in Digital Media and Technology. Plymouth: Lexington Books, 2012, pp. 199-220.

De Peuter, G., & Dyer-Witheford, N. (2009). Games of Empire: Global Capitalism and Video Games. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Dummy (2012, November 13). Fatima Al Qadiri Interview. Retrieved from http://www.dummymag.com/features/fatima-al-qadiri-interview

Eglash, R. (2002). Race, Sex, and Nerds: From Black Geeks to Asian-American Hipsters. Social Text, 20(2), pp.49-64.

Fade to Mind (2012). Fatima Al Qadiri – Desert Strike. Retrieved from http://fadetomind.net/music/eps/fatima-al-qadiri-desert-strike/

Feola, J. (2016, March 3). Primer: Sinogrime. Time Out Beijing.. Retrieved from http://www.timeoutbeijing.com/features/Bars__Clubs-Features/149126/Primer-Sinogrime.html

Guins, R. (2014). Game After: A Cultural Study of Video Game Afterlife. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Hancox, D. (2012, December 6). A History of Grime, by the People Who Created It. The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/music/2012/dec/06/a-history-of-grime

Hancox, D. (2013). Stand Up Tall: Dizzee Rascal and the Birth of Grime. UK: Kindle Editions.

Harper, T. (2014) The Culture of Digital Fighting Games: Performance and Practice. London: Routledge.

Howe, J. (2013). The History of the Emulator II Shakuhachi Flute Sample. Retrieved from http://goodpressgallery.co.uk/files/joehoweinfo.pdf

Kinder, M. (1991). Playing with Power in Movies, Television, and Video Games. London: University of California Press.

Kirkpatrick, G. (2011). Aesthetic Theory and the Video Game. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Meades, A. (2013). Why We Glitch: Process, Meaning and Pleasure in the Discovery, Documentation, Sharing and Use of Videogame Exploits. Well Played, 2(2), pp. 79-98.

Moriarty, B. (2002). Entrain. Retrieved from http://ludix.com/moriarty/entrain.html

Newman, J. (2008). Playing with Videogames. London: Routledge.

Parker, F. (2008). The Significance of Jeep Tag: On Player-Imposed Rules in Video Games. .. 2(3). Retrieved from http://journals.sfu.ca/loading/index.php/loading/article/viewArticle/44

Parker, F.(2015). Canonizing Bioshock: Cultural Value and the Prestige Game. Games and Culture. Retrieved from http://gac.sagepub.com/content/early/2015/08/28/1555412015598669.abstract

Poletti, A. & Rak, J. (Eds.). (2014). Identity Technologies: Constructing the Self Online. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press.

Reynolds, S. (2007). Bring the Noise: 20 Years of Writing about Hip Rock and Hip Hop. London: Faber and Faber.

Rodgers, T. (2003). On the Process and Aesthetics of Sampling in Electronic Music Production. Organised Sound, 8(3), pp.313-320.

Rose, T. (1994). Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America. Hanover: University Press of New England.

Ryce, A. (2010, November 17). The Devil Inside: Terror Danjah Talks Gremlins, Rhythm’n’Grime, and Nearly Throwing in the Towel. XLR8R. Retrieved from https://www.xlr8r.com/features/2010/11/the-devil-inside-terror-danjah-talks-gremlins-rhythm-n-grime-and-nearly-throwing-in-the-towel/

Salen, K. & Zimmerman, E. (2004). Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

Sandhu, S. (2014, May 5). Fatima Al Qadiri: “Me and My Sister Played Video Games as Saddam Invaded”.The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/music/2014/may/05/fatima-al-qadiri-interview-kuwait-invasion-saddam

Shaw, A. (2011). “He Could Be a Bunny Rabbit For All I Care”: Exploring Identification in Digital Games. Proceedings of DiGRA 2011 Conference.

Parker, F.(2014). Gaming at the Edge: Sexuality and Gender at the Margins of Gamer Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Surman, D. (2007). Pleasure, spectacle and reward in Capcom’s Street Fighter series. In. B. Atkins & T. Krzywinska (Eds.), Videogame, Player, Text. Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp.122-135.

Taylor, T.L. (2012). Raising the Stakes: E-Sports and the Professionalization of Computer Gaming. London: MIT Press.

Thieme, J. (2001). Postcolonial Con-Texts: Writing Back to the Canon. London: Continuum.

Twells, J. (2016, October 1). The 14 Pieces of Software That Shaped Modern Music. FACT. Retrieved from http://www.factmag.com/2016/10/01/the-14-pieces-of-software-that-shaped-modern-music/

Vernallis, C. (2013). Unruly Media: YouTube, Music Video, and the New Digital Cinema. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ward, P. (2002). Videogames as remediated animation. G. King and T. Krzywinska (Eds.), Screenplay: Cinema/Videogames/Interfaces . London: Wallflower Press, pp.122-135.

Discography

Al Qadiri, F. (2012). Desert Strike [MP3]. USA: Fade to Mind.

D.O.K. (2013). Chemical Planet [vinyl]. UK: Butterz. Audio available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YFS8sdn6mQs

D Double E (2010). “Street Fighter Riddim” [MP3]. Self-released.

Demon (2005). “I Won’t Change”. On Run the Road [CD]. UK: 679 Recordings. Audio available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q3eLO5odQfs

Dizzee Rascal (2004). “Street Fighter” [Vinyl]. UK: White label (Self-released). Audio available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Icute6aU0UM

Hanson, R. (2010). “Bowser’s Castle” [Recorded by Champion]. On Sons of Anarchy [Vinyl]. UK: Hyperdub. Audio available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HpHL29Tlbo8

Jammer (2004). “Thug”. On Mystic [Vinyl]. London: Jahmektheworld. Audio available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J0ro9ZVf8m8&index=5&list=PLE0kttgZnNZkxTj3YPgbdDiSsw-kmfkNv

JME (2005). “Baraka”. On Check It [Vinyl]. London; Boy Better Know. Audio available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9FH9xyFMcuM

JME (2006a). “Deceived”. Boy Better Know – Derkhead Edition Three [CD]. London: Boy Better Know. Audio available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J4eFT2d_aoc

JME (2006b). “Deadout”. On Boy Better Know – Shh Hut Yuh Muh Edition One [CD]. London: Boy Better Know. Audio available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f_n3qY9qsUU

JT the Goon (2015). King Triton [MP3]. UK: Oil Gang.

Mak 10, D Double E, Stormin, Wiley, Dizzee Rascal, Crazy Titch, Kano, Hyper, Esco, Armour, Tinchy Stryder, Jammer, Slix (2003). Deja Vu FM set unknown date [MP3]. Audio available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6j2p1bJIbvM

Newham Generals (2006). Rinse FM set 24/12/2006. Audio available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3CYfvPL63yQ

Newham Generals (2009). “Bell Dem Slags”. Words by Footsie (Daniel Carnegie) and D Double (Darren Dixon). On Generally Speaking [CD]. London: Dirtee Stank.

Professor Shyguy. (2013) Rhythm & Bloops [MP3]. USA: Self-released.

Royal-T (2009). “1Up”. On 1UP or Shatap [Vinyl]. London: No Hats No Hoods. Audio available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mMZwqJsepAE

Ruff Sqwad (2004). “Functions on the Low” [record]. London: White label. Audio available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nHLPU66yLFY

Ruff Sqwad (2012). White Label Classics [MP3]. London: No hats No Hoods.

Skepta (2006). “F*#kin Widda Team”. Boy Better Know – Shh Hut Yuh Muh Edition [1] [CD]. Boy Better Know. Audio available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kkg0DtAGgoc

Spyro (2008). Rinse FM set 13/02/2008 [MP3].

Wiley (2003). “The Morgue” [Vinyl]. UK: White label. Audio available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z0cV9p2-VOg

Wiley (2006). “Crash Bandicoot Freestyle”. On Tunnel Vision [CD]. UK: Boy Better Know. Audio available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ua4f1fXMXy0

Wiley (2013). “Step 20 Freestyle”. On It’s All Fun and Games Til… Vol. 2 [MP3]. UK: Self-released. Audio available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XyAhX7mgWJU

Wonder (2003). “What” [Vinyl]. London: Dump Valve Recordings. Audio available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XAPnIdiRKQQ

Ludography

Bioshock, 2K Boston, USA, 2007.

Castlevania, Konami, Japan, 1986.

Depression Quest, Zoe Quinn and Patrick Lindsey, USA, 2013.

Desert Strike: Return to the Gulf, Electronic Arts, USA, 1992.

Final Fight, Capcom, Japan, 1989.

Guitar Hero, Harmonix, USA, 2005.

Killer Instinct, Rare, UK, 1994.

Mario Paint, Nintendo, Japan, 1992.

Mortal Kombat, Midway, USA, 1992.

Music 2000, Jester Interactive, UK, 1999.

Quake III Arena, iD Software, USA, 1999.

Shinobi (series), Sega, Japan, 1987-2011.

Sonic the Hedgehog 2, Sega Technical Institute, USA/Japan, 1992.

Street Fighter II, Capcom, Japan, 1991.

Super Mario Bros. 2, Nintendo R&D 4, Japan, 1988.

Super Mario Kart, Nintendo EAD, Japan, 1992.

Super Street Fighter IV, Capcom, Japan, 2010.

Tekken, Namco, Japan, 1994.

A/V Sources

Lord of the Mics (2004). [DVD].

NightmareZer0 (2006, March 18). EVO Moment #37–Daigo (Ken) defeats Justin (Chun-li) [online video]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=np_5BHmaSI4

Stormzy TV (2015, May 17). “Stormzy–Shut Up” [online video]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RqQGUJK7Na4

Timandbarrytv (2007, June 17). Tinchy Stryder Freestyle [online video]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n1goKXMUlGs

Timandbarrytv (2010, July 29). D double E–streetfighter riddim OFFICIAL VIDEO [online video]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O8hi7CaqE8A

Acknowledgements

This research has received funding from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) as part of the Ego-Media project (ERC grant agreement no. 340331), which addresses the impact of new media on autobiographical narratives and practices of self-presentation.

Author’s Info

Rob Gallagher is a postdoctoral researcher with King’s College London’s Ego-Media project. His work addresses the role of digital technologies in fostering new conceptions of identity and forms of self-presentation. He is the author of Videogames, Identity and Digital Subjectivity (Routledge, 2017).

Endnotes:

- Cosplay (“costume play’”) involves dressing up as favourite characters from games and other media (see Newman, 2008, pp. 83-8). Speedrunners compete and collaborate to find the quickest routes through games (see ibid, pp.123-48). Glitch hunters systematically comb gameworlds looking for errors, exploits and logical quirks (see ibid, pp.113-6, and Meades, 2013). ▲

- Life writing studies, despite its name, is interested not just in texts but in the myriad media practices through which “the self or personality” is constructed, expressed, performed and recorded (see Poletti & Rak, 2014, pp. 20-23). Whether or not grime is a vehicle for verifiable biographical information, it certainly constitutes life writing on these terms, and rewards analysis from this perspective. ▲

- Chipmusic is defined by Carlsson as “music composed by using, emulating or sampling old digital sound chips” (2008, p.153). See also James Newman on chipmusic in this special issue. ▲

- “Skeng” (along with “mash”, “tool”, “leng” and many more) being grime slang for gun. ▲

- There is a tendency for journalists, seduced by the romantic notion of grime artists crafting hits on PlayStations in teenage bedrooms, to overstate the importance of games like Music 2000 to the scene; Braddock’s (2004) hyperbolic assertion that Music 2000 “is to today’s music what the guitar was to the pop boom of the 1960s” represents an early example. ▲

- Kirkpatrick’s argument resonates with Springer’s (1991) observation that at the very moment digital technologies seemed to be offering the prospect of transcending gendered embodiment, popular culture began to abound with “cyberbodies” made to “appear masculine or feminine to an exaggerated degree”, as if to counteract or compensate for any destabilization of gender norms (p.309). My thanks to the editors for highlighting this parallel. ▲

- Twitch is a platform for broadcasting play, including speedruns. More popular streamers often reach audiences numbering in the tens of thousands. ▲

- “Sinogrime” is a term coined by DJ, producer and academic Steve “Kode9” Goodman to describe the large subset of grime tracks which incorporate Chinese or “oriental” sounds and instruments (Feola, 2016). ▲

- As Chess and Shaw (2015) recount, gamergate mutated from a “harassment campaign” directed at Zoe Quinn, designer of the game Depression Quest (2013), into a “sustained online movement” united by its belief that feminists and “social justice warriors” were “actively working to undermine the video game industry” (p.210). Along with defamation and “doxxing” (the publication of sensitive personal data online), as well as rape and death threats, Quinn faced insistence that Depression Quest was “not a ‘real game’”(Berlatsky 2014), similar to Al Qadiri’s encounters with “trolls” appointing themselves arbiters of what counts as “real” grime. ▲

- Here it is instructive to compare Bioshock (2K Boston, 2007), Parker’s quintessential prestige game, and Quake III Arena (id Software, 1999). Both are considered significant first-person shooters. It is, however, much easier within the framework that our dominant critical vocabularies offer, to make a case for the cultural import of Bioshock (with its allohistorical critique of Randian politics and its reflexive exploration of free will and the player/designer relationship) than it is Quake––an exquisitely tuned platform for competition, but also a violent, gleefully tasteless mélange of horror and sci-fi clichés with little by way of a plot. ▲

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.