Abstract

Games can serve a critical function in many different ways, from serious games about real world subjects to self-reflexive commentaries on the nature of games themselves. In this essay we discuss critical possibilities stemming from the area of critical design, and more specifically Carl DiSalvo’s adversarial design and its concept of reconfiguring the remainder. To illustrate such an approach, we present the design and outcomes of two games, Jostle Bastard and Jostle Parent. We show how the games specifically engage with two previous games, Hotline Miami and Octodad: Dadliest Catch, reconfiguring elements of those games to create interactive critical experiences and extensions of the source material. Through the presentation of specific design concerns and decisions, we provide a grounded illustration of a particular critical function of videogames and hope to highlight this form as another valuable approach in the larger area of videogame criticism.

Keywords

Critical design, adversarial design, reconfiguration, videogame violence, emotion

The videogames discussed in this essay are freely available at http://www.unwinnable.com/2013/11/19/playable-jostle-bastard/ and http://www.unwinnable.com/2015/04/09/jostle-parent/.

Introduction

Videogames, like any medium, can be not just a target of critical engagement but a form of it themselves. Jostle Bastard (Barr, 2013) and Jostle Parent (Barr, 2015) are two videogames devised as direct critiques of two popular earlier videogames, Hotline Miami (Dennaton Games, 2012) and Octodad: Dadliest Catch (Panic Button Games, 2014). These games reify and thus make playable critical interactions with their source material, extending specific ideas that were introduced but not fully developed. As will be discussed, in both source games, reductive settings and narratives led to oversimplifications or missed opportunities for deeper engagement with their subject matter, ultimately prioritizing entertainment over meaning. Hotline Miami, while often championed as critical of videogame violence, largely contradicts the goals it sets in the actual experience it offers players, falling more on the side of celebrating violence than condemning it, while Octodad sacrifices the potential emotional weight associated with parenting to comic stereotypes and slapstick play. Both Jostle Bastard and Jostle Parent reconfigure central ideas from their source games in order to make alternate strategies of design and corresponding player experiences available. Importantly, these critical games are also able to operate independently of their source games even as they use them as a starting point for reconfigurations of design and narrative.

In this brief essay, the central idea of critical videogame design via reconfiguration will be explored through an examination of the design decisions made in creating Jostle Bastard and Jostle Parent. First, we will see how the notion of critical game design is developing alongside substantial contributions in other fields such as object design and interaction design, focusing more specifically on adversarial design. We will then review the critical functions of both Jostle Bastard and Jostle Parent with specific reference to the games they were created in response to, before summarizing the demonstrated potential of critique in videogame design and analysis.

Critical Design

The practice of design as a form of critique is well expressed in Anthony Dunne’s Hertzian Tales (Dunne, 1999). Here Dunne outlines a project (later expanded with Fiona Raby) to develop a design practice focused on a critique of what they label “affirmative design”. In a more recent discussion of the related area of speculative design, Dunne and Raby (2014) characterize affirmative design as “design that reinforces the status quo”, an approach that focuses on solving problems, innovation, and eventual consumption. Critical design, by way of contrast, offers oppositional concepts such as “post-optimal objects” and “user-unfriendliness” (Dunne, 1999) that seek to question and provoke, to find problems and lead us toward critical thought. In this practice, Dunne and Raby produce objects that function as reified critiques of design and technology. One of their best-known design objects is the Faraday Chair. It presents the audience with a small, enclosed space in which it is proposed we could shelter from the electromagnetic radiation that invisibly surrounds and penetrates our bodies. By explicitly stating its purpose, the artifact brings the audience’s attention to an unsensed aspect of our lives. It provokes us to question, for example, why we are not “protected” from this radiation and what harm it could do to us. In short, Dunne and Raby suggest that such objects can serve a critical function by provoking questions and reflection in an audience through experience and interpretation.

Naturally, matters are more complex than a binary of critical versus affirmative design. As discussed at length by Bardzell and Bardzell (2013), the question of what is and is not critical design may be quite a subjective matter, including the distinction with art proposed by Dunne and Raby. Bardzell and Bardzell suggest a constellation of properties of critical design by drawing on the traditions of critical theory and metacriticism: the ability to shift the perspective of the audience, a speculative or subjective nature, a dialogic methodology, encouragement of skepticism and sensitivity in interpretation, and reflexive awareness of limitations. Unsurprisingly, the Bardzells point out that many of these qualities are shared with art, blurring the any line we may attempt to draw between art and critical design.

Critical design has already been extended into the world of videogames both in terms of theory and practice by researchers such as Mary Flanagan (2009), Lindsay Grace (2011), and Rilla Khaled (2014). This has included perspectives such as Flanagan’s “critical play”, a design methodology focused on critical games, and Grace’s “critical gameplay”, a project of game creation with an emphasis on the self-reflexive critique of existing videogame tropes. These designer-scholars suggest and show how videogames can be imbued with a critical perspective on a great variety of subjects, from social issues to the physical nature of play to commenting on videogames themselves. What is especially interesting about introducing critical design to videogames is the potential for an interactive critique that players engage with actively and directly. Thus, while Dunne and Raby’s Faraday Chair functions as a pointer toward ideas, it is not itself a working object. Indeed, much critical design is of such a speculative nature, functioning more as a thought-experiment or exemplar. James Auger and Jimmy Loizeau’s (2001) Audio Tooth Implant, for instance, created an imaginary tooth implant for communication that never existed beyond a mockup, and instead drew its critical force from media attention allowing the public to confront this idea “in the wild”. In contrast, critical videogames can leverage their very real mechanics and gameplay to communicate their critical perspective through play itself. Videogames are real, functional objects in this world that players can not only think about, but directly interactive with and experience.

Adversarial Design

A direct point of connection between the more speculative world of critical (object) design and the functional world of critical videogames can be found in Carl DiSalvo’s (2012) discussion of adversarial design. This is a form of critical design focused specifically on interactive technologies which “evokes and engages political issues” but does so “through the conceptualization and making of products and services and our experiences with them” (p. 2). This active creation of experience through working products is central to the adversarial project. Especially relevant in the tactics of adversarial design offered by DiSalvo is the notion of “reconfiguring the remainder” in which:

[t]he activity of reconfiguration leverages an understanding of the standards of configuration, both technically and socially. It works by manipulating those standards and addressing what is left out of common configurations, which can be referred to as “the remainder”. (p. 63)

Reconfiguring the remainder involves the idea of taking standard design and technical practices and shifting them in relation to one another in order to highlight elements that may otherwise not be seen. DiSalvo illustrates this with the example of Kelly Dobson’s (2007) Blendie, an artwork consisting of a blender that responds to human sound only if the human performs the strenuous task of mimicking the sound of a blender. Here critical design ideas surrounding transparent voice-based interaction with technology alongside the drive for humans to adapt themselves to technology are brought to the foreground through an uncommon and disturbing form of interaction that reconfigures conventional and expected product use.

Critical videogame design very often uses this reconfiguration of conventional videogame design tropes. The “remainder” in such cases is the possibilities dormant or excluded in conventional or “affirmative” approaches to design while the reconfigurations are of design decisions and implementation details often taken for granted. We can thus see videogames critiquing videogames as a form of critical reconfiguration to explore latent possibilities of specific design frames. Crucially, as already noted, reconfigured videogames still continue to function as videogames. Their critical power comes from their ability not just to be seen or heard, but to be played.

For the remainder of this article, we will explore two specific examples of this approach of reconfiguring the remainder in critical game design. While sharing some similarities particularly with Lindsay Grace’s “critical gameplay” project, here the point is the explicit reconfiguration of pre-existing videogames into new forms that comment on and extend their predecessors.

Jostle Bastard: “I’m Here To Teach You How To Jostle”

The highly successful arcade-style beat-em-up game Hotline Miami (Dennaton Games, 2012) is set in a dark and seedy world. The player is sent out by mysterious answer phone messages to kill waves of gangland tough guys. The player spends most of their time plotting paths through spaces in order to kill everyone and then escape past their inert bodies and pools of blood. The game was explicitly created with a critique of videogame violence in mind, its creators stating that they “wanted to show how ugly it is when you kill people” (Smith, 2013). This was reflected in the game’s presentation of visual and mechanical violent excess through a self-reflexive lens. Throughout, the designers are intent on emptying meaning from the violence as a critical take on players’ general acceptance of violent acts during play: the game is repetitive and solely focused on violence and alienation in the form of extended action sequences in which the only resolution is to kill everybody and more “social” scenes that depict the player’s character as completely dissociated from everyday life. Indeed, at the end of the game, a scene breaks the fourth wall with two janitor characters effectively to accuse the player explicitly as someone entranced by violence who needs to examine their motives and goals with dialog such as “we haven’t killed anyone, you have…” and “you’ve done far worse things than we have, haven’t you?” (Dennaton Games, 2012).

Despite its interesting intent and design moves, Hotline Miami is an awkward fit for a critique of videogame violence. A central difficulty is that when violence and murder constitute the core form of interaction and are inescapable in order to progress through the game’s narrative structure, there is no decision with consequences to be made by the player, and thus no ethical quandary. The horror of the piles of bodies at the end of each level is undercut both by the necessity of their death (mechanically speaking) and by the game’s explicit validation of the player’s actions through an elaborate scoring system. While it might be that, as in War Games (1983), “the only winning move is not to play”, this is hardly satisfactory in the context of a medium whose only purpose is to be played.

Jostle Bastard is a reconfiguration of elements of Hotline Miami in an attempt to provide a critical response to questions of videogame violence by leveraging DiSalvo’s concept of reconfiguring the remainder. Here the remainder is the omission of the consequences of violence beyond the player’s immediate visceral response. Centrally, Jostle Bastard replaces the central action of “killing” in Hotline Miami with the far less drastic verb of “jostling”. Through a simple physics implementation, the player’s core interaction becomes that of repeatedly bumping into objects and people. By moderating the violent act to one of non-fatal aggression, players are pushed to confront the social ramifications of injuring, intimidating or inconveniencing another person physically. When jostled, other characters in the world may fall down, flee in fear, or even jostle back, giving the violence an evolving social context. Ironically, by dialing back the extremity of physical harm possible, the game makes that violence more actively present in the experience of the player.

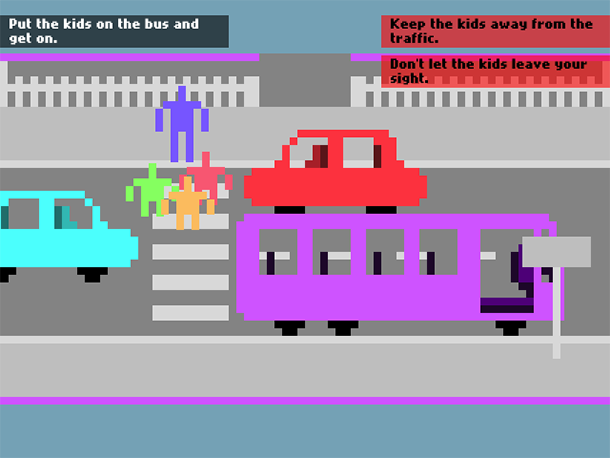

The police arrive after the player jostles students in class in Jostle Bastard (Barr, 2013).

Developing this idea of violence taking place in a social context, there are major consequences in the game for the simple act of jostling or being jostled. Scenes largely take place in public places such as cafés, movie theatres, and parks, so if the player creates too great a public disturbance someone will call the police. If the player remains, the police will arrive, arrest her, and take her to jail. The more often the player is arrested, the longer she must spend in a cell before being released. Similarly, the player works as a teacher at the start of the game but, of course, can lose this job if she is violent in the classroom. If she persists in violent behaviour, in fact, the player may end up unemployed and evicted from her apartment, sleeping in public parks and wandering from scene to scene. This disintegration of the player’s life and social relations as a consequence of violent behaviour reconfigures Hotline Miami’s extremes into a more nuanced and realistic representation of the impact of violence on day-to-day life.

As in Hotline Miami, Jostle Bastard would still offer a problematic representation of violence if the player had no other options, so the game also includes the possibility of pursuing an “ordinary” life. The player can teach a class of children, buy a coffee at the café, watch a movie peacefully, and so on. These forms of interaction may be far less exciting than creating mayhem, of course, but they do serve as a contrast, problematizing any violence as not strictly “necessary” to the narrative of the world. This enables players to think critically about the idea of violence as “fun” without the excuse of it being mandatory.

As a dynamic system, Jostle Bastard also revealed possibilities for emotional distress that were not explicitly designed for. This was exemplified in one tester’s experience with the “revenge” element of the game: if you are violent in Jostle Bastard there is a chance that your victims may return later with reinforcements to get payback, jostling you mercilessly. In this instance, the tester had followed the predictable path of jostling people, being jailed repeatedly, and losing his teaching job. This creates a stressful situation in the game, of course, but this player then decided to “go straight” and behave like a decent person. He performed his new job quietly, went to the movies, and sat in the park. Despite his peacefulness, a group seeking revenge for being jostled earlier burst onto the scene to retaliate. He did not fight back, but the police were summoned and he was jailed again as the underlying code of the game does not distinguish who is jostling whom. The tester thus found himself at the mercy of both an unjust legal system and his history of violence; even “going straight” was no longer an option.

Jostle Parent: Three Lives

Jostle Parent was created to serve as a critique of design decisions made in the popular physics-engine-comedy game Octodad: Dadliest Catch. In Octodad the player must awkwardly manipulate the limbs of an octopus pretending to be a human to solve seemingly simple challenges such as pouring a glass of chocolate milk or mowing the lawn. The physics-based interface is very literal, leading to slapstick comedy as the player flails incompetently.

The most interesting feature of Octodad for our purposes is that it introduces an emotional dimension. By framing the protagonist as fearful of being discovered as an octopus and thus losing his family, there is a significant focus on his valiant attempts to be a good parent to the children he loves while under duress of the constant threat of exposure. This emotional core is, however, undermined by the game’s linear narrative: failing (notably, being detected as an octopus) leads only to restarting a “level” of play. There is ultimately only one narrative, the one in which Octodad is successful. Any sense of emotional consequence experienced in moment-to-moment play is quickly eroded as the player realises there are no narrative or other ongoing social consequences of their failures. This, along with the explicitly comic approach to the subject matter, means Octodad offers very limited emotional tones.

Jostle Parent escalates the potential emotional drama and risks of parenting by reconfiguring the elements of Octodad’s scenario into a more “realistic” simulation of possible consequences. In fact, in the process of reconfiguration the source game itself takes a back seat: unlike Jostle Bastard, Jostle Parent does not rely on explicitly referencing Octodad to bring forward its critical point. Taking its cue from Jostle Bastard, the protagonist of Jostle Parent is only able to “jostle” as his primary interaction with the world. Using this action, the player is asked to take care of the protagonist’s three children over the course of a day, waking them up in the morning, feeding them breakfast, taking them to the park and beach, and so on. During this day the player must focus on bodily pushing the children around the environments as well as colliding with certain objects in order to interact with them (jostling food out of the refrigerator, for instance). This task is already difficult enough, and mirrors Octodad’s struggles to perform banal daily tasks, but Jostle Parent includes the very real possibility that the children might die. The hazards include faulty electrical sockets, deep water, and busy roads, all of which the player must skillfully navigate the children around. Without the comfort of a linear narrative and a happy ending, the anxiety and emotion of the game are centered not on the idea of being temporarily unmasked as a fraud (an octopus) before resetting, but of being revealed once and for all to be the worst kind of parent, one who lets their children die.

Many of the design decisions in Jostle Parent were aimed at building a sense of responsibility and emotional investment in the lives of the children. The children have their own names, for instance, (shown through surtitles) and these names are announced if they die, removing any idea of a “generic” child. Throughout the game the children also act like children, clinging to the protagonist, playing happily with toys or watching television, while also constantly wandering around their environment. All these features help to make the children sympathetic, independent agents with their own inner worlds in order to emphasize their individual value to the protagonist. The simple activities in the game, such as playing with a ball or swimming, are intended to give a sense of everyday realism through their very lack of drama.

Jostle Parent thus takes Octodad’s nod to the stresses and consequences of parenting to an extreme in order to show how an intense emotional commitment could be achieved. Most centrally, consequences in Jostle Parent are permanent: if a child dies in the game the protagonist visits the grave with the remaining children and the day restarts. While this seems like a standard videogame “reset” after a lost life, the deceased child’s bed is empty and they are instead represented as a gravestone in the graveyard from this point on. In many games, players have three “lives” to help get them through the various levels; here the three children are a literal version of those “three lives”, representing a judgment of the player’s performance of parenting. Somewhat ironically, the gameplay itself becomes easier with each child’s death as there is less multitasking required.

Ultimately, the remainder revealed by Jostle Parent’s reconfiguration of the tropes and mechanics of Octodad is the potential for emotional engagement and tragedy by embracing permanent consequences in design. The player of Jostle Parent feels a similar stress to the player of Octodad in the sense of the difficulties of micromanaging a physical simulation, but only the player of Jostle Parent knows that if they fail, the child in their charge will die and, perhaps worse, they will have to play on without them rather than restart. There are thus multiple narratives the game might follow, acknowledging that a central element of evoking deep emotion is knowing things could have been otherwise. In fact, the protagonist himself can also die in certain circumstances and become a ghost. They are able to watch any remaining children asleep in bed but are no longer able to care for them – perhaps the ultimate tragedy for a parent.

Summary

Games can be critical in a great variety of ways, from serious games about real world subjects to more inward-gazing self-reflexive commentaries on the nature of games themselves. In this essay we have discussed two games, Jostle Bastard and Jostle Parent, in terms of DiSalvo’s concept of reconfiguring the remainder. When we reconfigure the remainder in videogames, we shift the structures of more conventional designs in such a way as to make apparent assumptions or absent possibilities. Both Jostle Bastard and Jostle Parent reconfigure their source games to bring out and highlight an omitted or missed “remainder” centered around the often neglected ideas of consequence and tragedy in mainstream design.

Jostle Bastard reconfigures Hotline Miami’s frictionless violence by shifting it to a social environment where violence matters beyond its visceral and visual horror. By reducing the actual violence performed, the game makes that violence harder to avoid as a consequential act. Jostle Parent reconfigures the emotional play gestured toward in Octodad by introducing real consequences in a non-deterministic world in which such emotion can be registered and experienced – a mechanically “unsafe space” in which to fully engage with tragedy. Both games thus reconfigure their sources in ways that both critique existing design strategies but also productively suggest alternative possibilities that are valuable in their own right. The design and development process required by reconfiguration is a specific critical outcome in itself, but most importantly allows real players both to contemplate design norms and tropes they are familiar and to suggest new ideas and experiences that might be possible through alternate design practices.

Review excerpts

Click here to read excerpts from the reviewing process.

References

Auger, J. and Loizeau, J. (2001) Audio tooth implant. Retrieved from http://www.auger-loizeau.com/projects/toothimplant.

Bardzell, J., & Bardzell, S. (2013). What is “Critical” About Critical Design? In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 3297–3306). New York, NY, USA: ACM.

DiSalvo, C. (2012). Adversarial design. Boston, MA: MIT Press.

Dunne, A. (1999). Hertzian tales. Boston, MA: MIT Press.

Flanagan, M. (2009). Critical play. Boston, MA: MIT Press.

Grace, L. (2010). Critical gameplay: design techniques and case studies. In K. Schrier & D. Gibson (Eds.), Designing games for ethics: models, techniques and frameworks (pp. 128-141). Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Hotline Miami, Dennaton Games, Sweden, 2012.

Jostle bastard, Barr, P., Malta, 2013.

Jostle parent, Barr, P. Malta, 2015.

Khaled, R. (forthcoming 2016). Questions over answers: reflective game design. In D. Cermak-Sassenrath, C. Walker, & T.T. Chek (Eds.), Playful subversion of technoculture: new directions in creative, interactive and entertainment technologies. Singapore: Springer.

Octodad: dadliest catch, Panic Button Games, USA, 2014.

Smith, E. (2013, March, 18). Violence in videogames is boring say hotline Miami creators. International business times. Retrieved from http://www.ibtimes.co.uk.

United Artists (1983) War Games.

Author contacts

Pippin Barr – Pippin.Barr@concordia.ca

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.