Karen Collins (University of Waterloo, Canada)

The challenge of making a playlist for game sound

The sounds of video games have changed tremendously over their history, from about 1971 until now. Having been born approximately when commercial video games were first created and then growing up alongside the games as they evolved, the history of video games is very much a history of my own soundscape as it changed over the years. I had a Pong clone (a Telstar Alpha, made by Coleco) in the late 1970s, an IBM PC (the 5150, released in 1983), an Atari 2600, and then later Nintendo NES, Sega Genesis, PlayStation, and so on. What consoles I didn’t own, my neighbors usually had (the Apple II, Colecovision, Intellivision, and so on), or my school (the Commodore 64), and I spent many hours of my childhood playing these games.

the games listed below are the games that stuck in my head over the decades of playing games myself, and became important to me personally through the hours I spent with them. Some have admittedly “terrible” sound by today’s standards, but to me, that’s part of their charm, and growing up with these games means they hold a special nostalgia that I believe is best captured in their sound, even more than their graphics.

Being asked to make a playlist for game sound has always been a challenge for me. I have stayed away from lists as much as possible in the past, in the interests of not developing a canon for video game music. To me, there are far too many games deserving of our scholarly attention, and yet we in the field already seem to be focusing on just a few games, and a few genres of games, at the expense of others. Despite my long-time interest and expertise in the field, I also don’t feel that I am qualified to decide which games are particularly important, or which are especially worth listening to or highlighting. My list below, then, isn’t a “most important” or even “particularly notable” games when it comes to their sound and music. The list doesn’t cover all of the consoles by any means, and anyone looking for a “best of” is sure to be disappointed by some of my inclusions and omissions. I take the title of my article from “Desert Island Discs”, a radio show created in 1942 by Roy Plomley for BBC Radio 4, which would bring a celebrity guest onto the program and ask them to choose eight recordings to take with them if they were cast away on a desert island. They were not meant to be bests of anything, only personal picks that held some meaning, which the guest would explain.

Therefore, the games listed below are the games that stuck in my head over the decades of playing games myself, and became important to me personally through the hours I spent with them. Some have admittedly “terrible” sound by today’s standards, but to me, that’s part of their charm, and growing up with these games means they hold a special nostalgia that I believe is best captured in their sound, even more than their graphics. Some were games whose composers I have since met, befriended and/or interviewed and are now of interest to me for that reason. Some indeed are usually in top ten lists or were the “first to do something” games, but are chosen here simply for their place in my heart, not for their place in history.

The list is supplemented by interview material I gathered during a year of filming interviews for the Beep documentary film (Ehtonal 2016). This documentary is a history of game sound from the penny arcades to today, and involved over 80 interviews with composers, sound designers, voice actors, and others involved in game sound from around the world (shot in UK, Canada, US and Japan, but also including interviews with composers from Germany, Spain, France and the Netherlands). Each full interview is released as an independent webisode, as well as in my two-volume book series Beep (Ehtonal 2016). The clips described here have also been assembled into one video that can be streamed or downloaded from our Vimeo website.

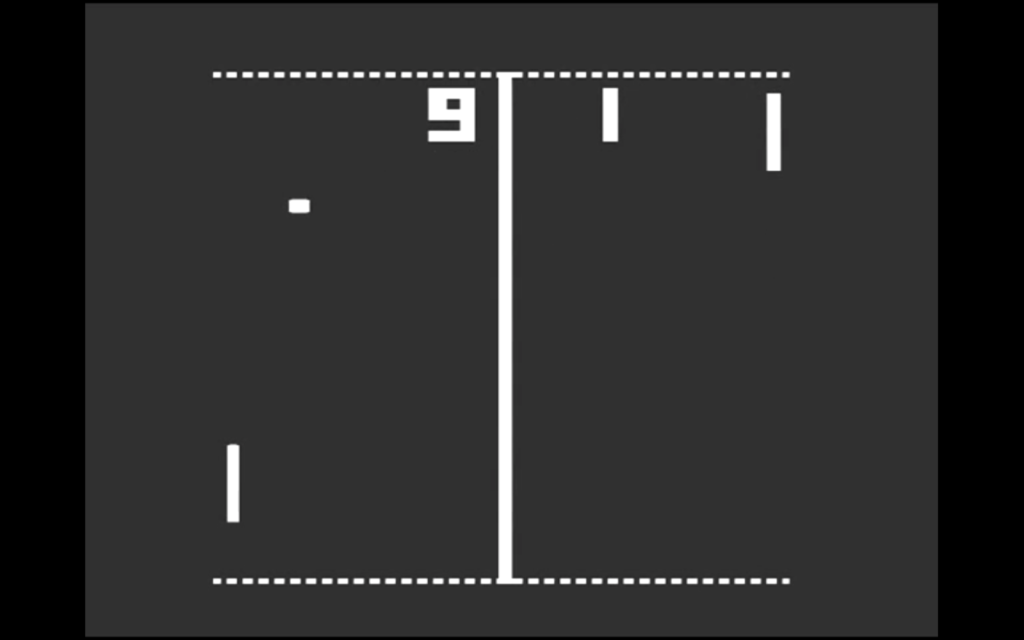

1 – The Telstar Pong Clone: (Coleco 1976): original Pong sounds by Al Alcorn at Atari

Pong was originally developed in 1972, and was the first commercially successful video game. The home version was sold through Sears starting in mid-1975, but it was one of Coleco’s Telstar models that my Uncle purchased one Christmas in the late 1970s that was my first foray into video gaming. The game had no music, and only made simple analogue beeping sounds of different frequencies for the four games (all simple variations on Pong) built into the system, but to us children at the time, being able to control something on the television set cannot be overestimated in importance. The game was captivating, and we spent many hours listening to the beeps. Compared to the Magnavox Odyssey, which was also available as a home console at the time, the Pong clones were a huge leap forward for the simple fact that they had sound at all. There isn’t a whole lot of interest here sonically, but I can still remember hearing those sounds in my head a long time after the game was set aside.

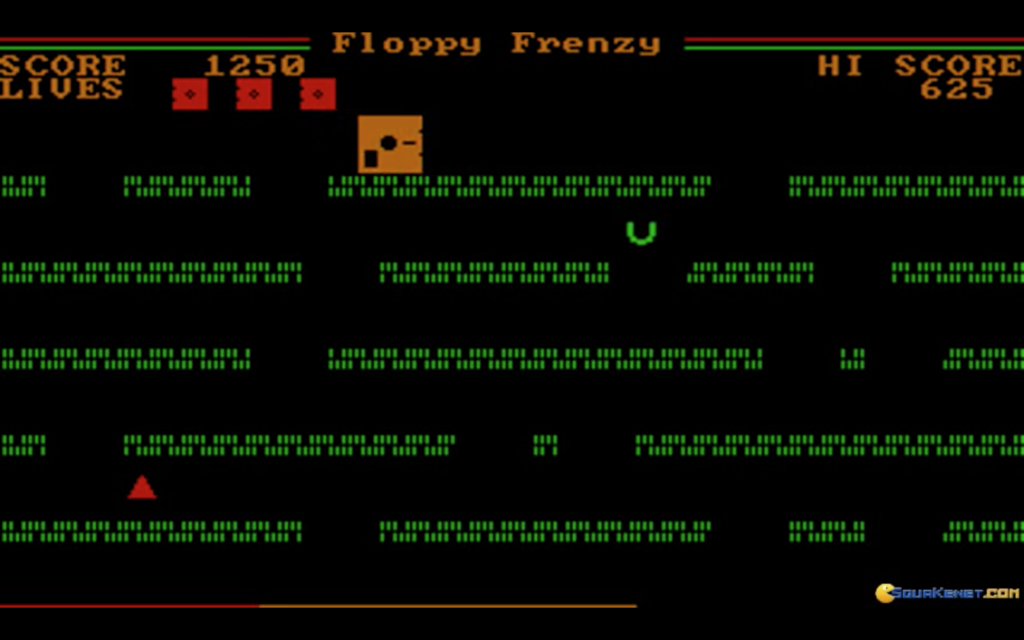

2 – Floppy Frenzy for the PC Beeper (Windmill Software1982): Unknown composer

Floppy Frenzy was a little-known game that must have been one of the very first educational video games. My father brought the game home with the computer, to teach us children not to put the 5¼-inch floppy disks near magnets or dust. Movement triggers the soundtrack: stop the diskette from moving, and the sound stops. Move, and the sound continues its monotonous, never-ending beeping—a trait also found in DigDug (Namco) that came out the same year. It’s unlikely that the games were created in the knowledge of what each other was doing, since Windmill was Canadian and Namco based in Japan, so the idea of tying game sound to the action of the main character (very much Mickey-Mousing the sound) may have been independently created, simultaneously. The game also had little bonus, high score and death jingles. It’s the death song that sticks with me more than anything (heard at approximately 9:45 into this video): not only did players use to spend a lot of time “dying” in early video games but to me, today, the song epitomizes my experience of audio on the IBM PC: a single monophonic channel playing simple on/off square wave sounds in very short melodies. This was PC sound before soundcards: monophonic, without sound envelope generators, and dreadfully annoying, which is probably where the original option to turn the sound off in games (still present in most current games) came from.

3 – Tapeworm for the Atari 2600 (Spectravision 1982): Unknown composer

Tapeworm still fascinates me. Its atonal melody that introduced the characters of the game at the start was a wonderful representation of the limitations of the Atari 2600 TIA soundchip. Sounds on the Atari chip were created by dividing the system clock into 32 notes. These notes didn’t align with just tuning, and the selection of each original note and waveform determined the division of frequencies of the other 32. This meant that each tuning was completely different depending on the first note selection, and for the most part completely atonal, resulting in some bizarre musical creations. I believe that the many hours of my childhood spent in front of the machine were a strong influence on my later musical tastes and even on the development of electronic music in the 1980s general (see Collins 2006).

Beep video clip: The first clip in the video features several of our interviewees talking about the infamous TIA soundchip and its difficulties. First is Brendan Becker, a chiptune composer known as “Inverse Phase”, famous for his Nine Inch Nails 8-bit cover album, Pretty Eight Machine. This interview was recorded at the annual MAGFest (Music and Games Festival) in January 2015 in Maryland. The second clip is pinball/game composer David Thiel, recorded at his home studio in Seattle in May 2015. The third is founder of music software company Plogue Art et Technologie, David Viens. Plogue makes the popular soundchip emulator software called chipsounds, and the clip was recorded in Montreal in June 2015. It’s easy to see that all of these folks have a love-hate relationship to the TIA chip: part of its appeal was its mix of very awkward tuning and rich waveforms.

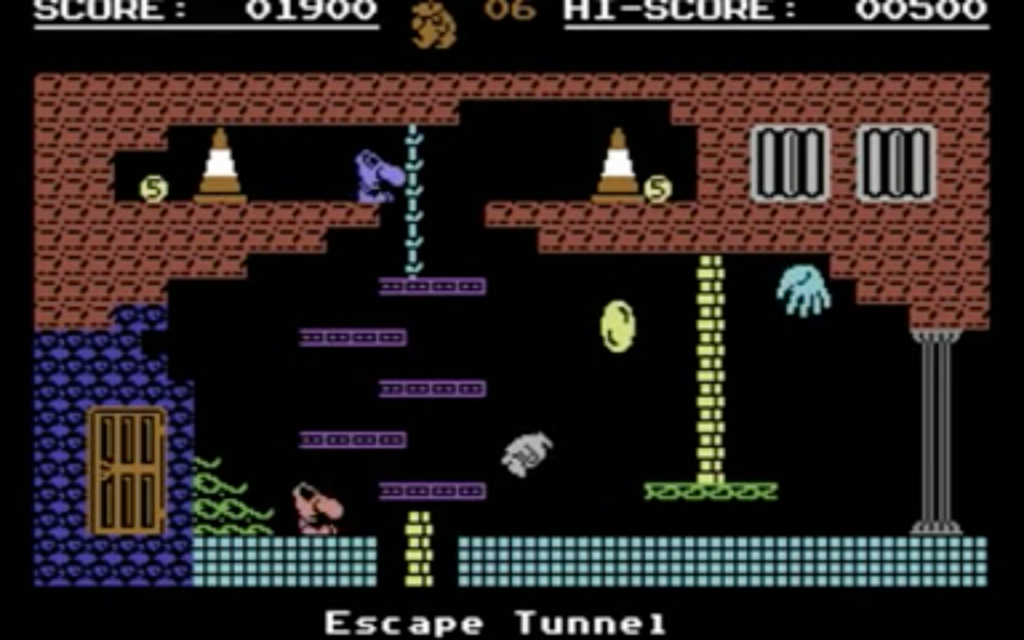

4 – Monty on the Run for the Commodore 64 (Gremlin Graphics 1985): Rob Hubbard

The Commodore 64 had a much more advanced sound chip than its competitors. I didn’t have a C64 at my house, but we had one at school and were allowed to play games at lunch time and during breaks. I remember playing Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? (Brøderbund 1985) a lot, but not Monty in those days. However, when I began research for my book Game Sound (2008), I played just about every game ever released for the C64, and Monty’s theme was one of the songs that stood out for me amongst the lot. Created by Rob Hubbard, the theme uses Hubbard’s module format, a way of maximizing the amount of music that could fit into a game by using loops, instrument changes (selections of sounds by picking waveforms and using envelope generators) and transpositions. Because the size of media and RAM was limited, there was a limited amount of space allocated to music. Through simple transposition statements, the same blocks of code could be re-used without the music sounding so repetitive.

Beep video clip: In this clip, German game composer Chris Huelsbeck talks about the Commodore 64 soundchip, followed by Charles Deenen, who explains some of the RAM issues. Both interviews were recorded in San Francisco in March 2015.

5 – Metroid for the NES (Nintendo 1986): Hirokazu “Hip” Tanaka

Metroid, along with Super Metroid on the SNES was, and still is one of my favourite games. The Metroid soundtrack was so different to nearly everything else that came out on the Nintendo. It used the NES soundchip to full advantage, but more than that, it didn’t have the poppy “chippy” sound of so much of the music. The bass channel creates pedal tones that the melody rests on for the Brinstar level, but it’s the Ridley and Kraid stages, with its sparse ambience, that captivated me as a young gamer. Not only did the music inspire in me a love of game audio, it’s also one of those game soundtracks that inspired others to become game composers, such as Alexander Brandon (who composed for Deus Ex, Unreal and more).

Beep video clip: In this clip, recorded March 2015 in San Francisco, game composer Alexander Brandon talks about the importance of Metroid to his career.

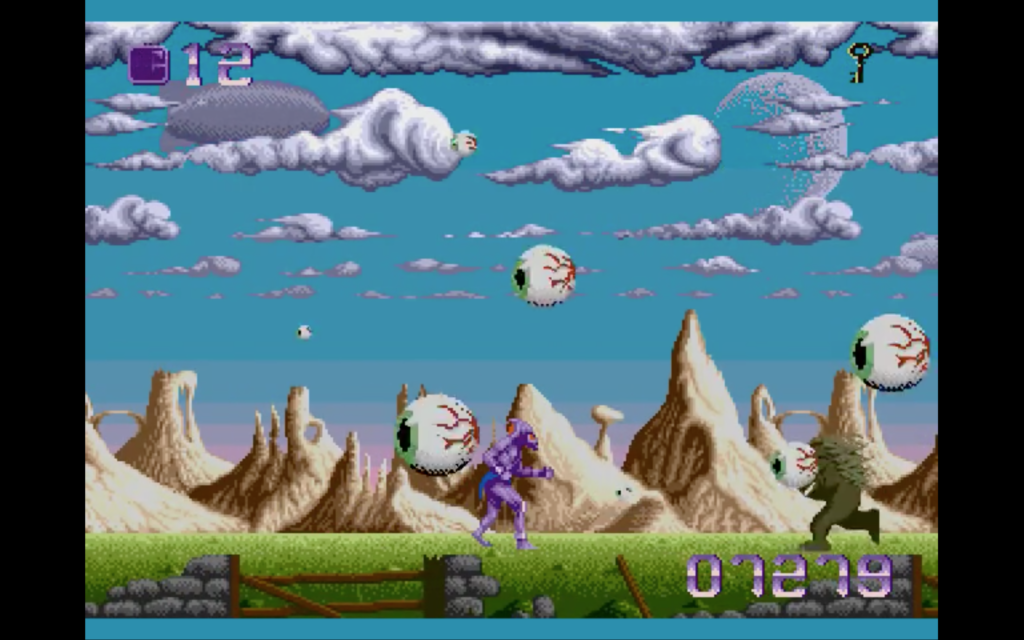

6 – Shadow of the Beast for Sega Genesis (Psygnosis 1989) David Whittaker

The Shadow of the Beast game bears some resemblance to Metroid, which is probably why I really liked the game and its music when it first came out for the Sega Genesis. You’ll notice we’re still in the era of “wall-to-wall” music: non-stop looping background music. The repetition of the really happy chip music of the time tended to grate on me (and most other people in the vicinity at the time), but the more moody, slightly prog-rock styling of Psygnosis games in particular were a wonderful change from that style. Music on the Genesis (or MegaDrive as it was known in Europe and Japan) was created using a combination of FM synthesis as well as the more primitive waveforms of a programmable sound generator (the chip type used up to that time). It was the newer digital FM synthesis chip, which allowed for more realistic instrument sounds that could be programmed in by the composer individually, which defined the Genesis sound.

7 – Monkey Island 2: LeChuck’s Revenge for the PC (LucasArts 1991): Michael Land, Clint Bajakian/Peter McConnell

Monkey Island 2 was the first game to use LucasFilm Games’ new (at the time) software engine, iMUSE, or Interactive Music Streaming Engine. iMUSE enabled the game’s parameters to control what was happening in the music—if a player was winning a battle, the music could jump to a different cue, and if a player was moving around a space, the music could adjust to the location. The infamous Woodtick scene, for instance, changes music depending on which building the player enters. Although the techniques had been used previously in games, iMUSE made it easier for composers to have control over how music played back in the game.

Beep video clip: In this clip, the three creators of the iMUSE engine—Clint Bajakian, Michael Land and Peter McConnell—discuss iMUSE and the difficulties of the Woodtick scene and interactive music as a whole. All interviews were recorded in San Francisco in March 2015.

8 – Tomb Raider for PSX (Eidos 1996): Nathan McCree

Tomb Raider was the reason I bought a PlayStation. Not only did the game have a female protagonist, but the wall-to-wall music of the past was suddenly replaced by the game’s more careful attention to ambience and using music more sparsely only to highlight key points in the narrative while showing a cinematic approach to the score. In an interview with Nathan McCree, he explained his choices about abandoning the wall-to-wall music in favor of ambience. In part, this shift was influenced by the switch to Redbook (CD-ROM)-based games, which allowed for higher production values, but reduced the amount of interactivity possible in the music. For a time, the concepts of interactive music dream of iMUSE was abandoned in favor of linear tracks, as composers adapted to the new format. McCree explained to me that he had no say in the implementation, which had been done on the last possible day before the game was shipped, and in some cases music was put into the wrong place or not as he had intended, but fans of the game never seemed to notice.

Beep video clip: Composer Nathan McCree talks about the change in the move to CD-ROM with the PlayStation and how that influenced the music and sound of Tomb Raider. The clip was recorded in London in February 2015.

9 – Wild Arms for PSX (MediaVision/Sony 1996): Michiko Naruke

I’m a fan of Ennio Morricone’s music for Sergio Leone’s “Spaghetti Westerns”, and so Wild Arms was a personal favorite not so much for the game, but for the heavily Morricone inspired music. The driving rhythms and some of the themes are close to being lifted directly from Morricone themes, but Naruke puts her own spin on them, and the nature of the role-playing game being set in a cross between the American West and medieval Europe meant a combination of Western themes and more traditional Japanese RPG musical elements.

Beep video clip: Michiko Naruke discusses Morricone’s influence on her music for the Wild Arms series. The clip was recorded in Tokyo in May 2015. My interpreter was Alwyn Spies.

10 – Legend of Zelda Ocarina of Time for Nintendo 64 (Nintendo 1998): Koji Kondo

No list of my favorite game music would be complete without some Koji Kondo somewhere. The composer for Super Mario Bros and the Zelda series is without doubt many people’s favorite. Along with frequently being listed in the Top Ten Games of all time, The Ocarina of Time’s music is also among many top 10 lists. The music is carefully integrated into the game, drawing on past themes established in earlier Zelda games, but adding new music and allowing player interaction with the music in the form of an ocarina. I’m convinced that the game inspired sales of ocarinas the world over––indeed, there are many Zelda-themed ocarinas for sale. For me, the theme-driven nature of Kondo’s music, combined with the careful integration of the music into the game itself, represents some of the best that game music has to offer.

11 – Grim Fandango for PC (LucasArts 1998) Peter McConnell

I first wrote about Grim Fandango in my 2008 book Game Sound. At the time I researched and wrote the book, the game had been out for a few years, and hadn’t really had a huge following or notable public interest, but was near the top of my list straight away. The game has since become a cult favourite, particularly amongst music fans. Peter McConnell’s delightful orchestral music fits the game so well—a mixture of the dark underworld Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead) and mariachi. To me, Peter McConnell is the Danny Elfman of the game music world—he writes playful, humorous music with highly memorable themes, and the Grim music is no exception.

Beep video clip: The music was re-recorded and re-orchestrated for the remake of the game in 2015, and I spoke with both Peter McConnell and the recording engineer, Jory Prum, about the work that went into the remake. They both talked about the difficulties with recovering the original files to remake the music. Jory’s interview was recorded in his studio in Fairfax, California, and Peter’s clip was recorded in San Francisco in March, 2015. Jory passed away suddenly in April of 2016, and thousands of people flooded the internet to express how much his work meant to them, despite his being very much a “behind the scenes” person in game audio.

The soundtrack for Harmony of Dissonance was much maligned by the press, largely for its 8-bit aesthetic, but also for its dense layers and morose themes. I’ve always enjoyed the Castlevania games and their music, but to me, the nature of the music as more complex, fitting the game well, and its 8-bit sound are precisely why I like this soundtrack. The music always heads in unexpected directions, and although it has fewer immediately recognizable themes or melodies, it offers a lot of sonic interest despite having being created on the Game Boy Advance’s crunchy speaker and four-tone (plus sample channel) synthesizer chip.

13 – Mario and Luigi: Partners in Time for Nintendo DS (Nintendo 2005): Yoko Shimomura

Yoko Shimomura tops my list of favorite game composers, and although her more famous work lies in Street Fighter 2 and the Kingdom Hearts series, it’s the Mario and Luigi role-playing games that I find most endearing. Shimomura had to take the well-known and well-loved Mario musical style and make it her own for the games, a difficult task, but she manages to give each game its own characteristic style and memorable themes. It’s worth noting that playing games on the Nintendo DS are always better heard with headphones rather than the limited speakers present in the DS.

Beep video clip: Yoko Shimomura talks about writing the music for the series and balancing adaptations of the original Mario tunes with her own style. The interview was recorded in Tokyo in May 2015, and my interpreter was Alwyn Spies.

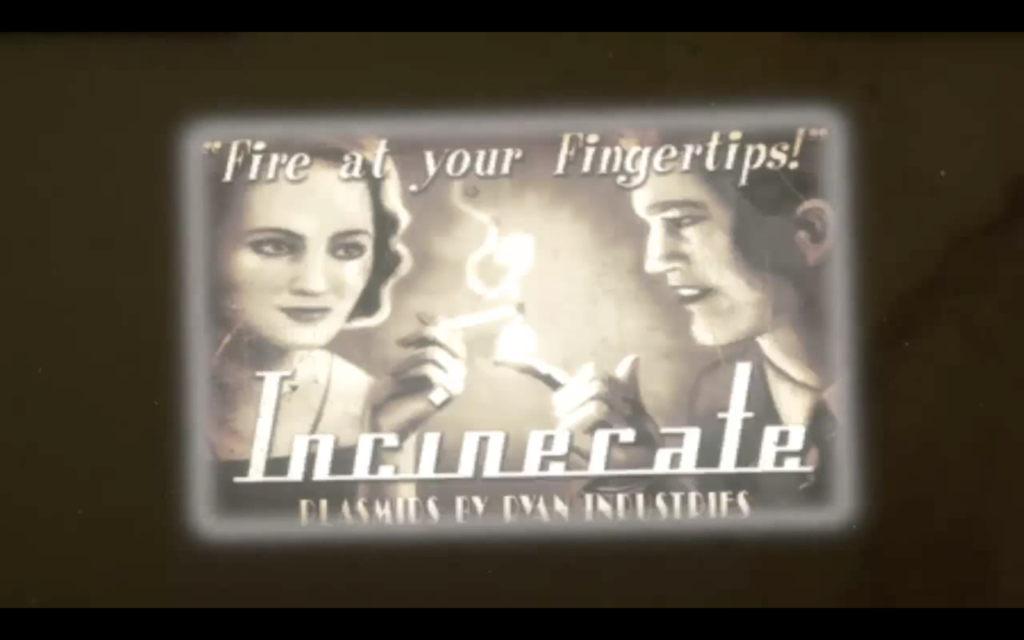

14 – BioShock for Xbox 360 (2K Games, 2007): Garry Schyman

BioShock was the first game music that left me absolutely speechless. I first became aware of the music when I heard Schyman give a talk about it at the Game Developers’ Conference in 2007. BioShock’s dramatic orchestration and sound design blew away everyone’s expectations of what game music was, and what it could be, inspired by 20th Century modernism. I’m also a big fan of Schyman’s other music, which ranges from Bernard Hermann-esque Destroy All Humans to the beautiful Dante’s Inferno.

Beep video clip: Here, Garry Schyman talks about the direction he received from audio director Emily Ridgway for the BioShock game. The interview was recorded in Los Angeles in October, 2014.

15 – Peggle 2 for Xbox One (XBLA: PopCap 2014): Guy Whitmore

Another soundtrack to blow away everyone’s expectations of game music was Peggle 2. A casual game created by PopCap, the first game Peggle originally established the theme of playing Beethoven’s Ode to Joy upon each level’s success in a game that combines elements of pachinko and pinball. For Peggle 2, Whitmore plays on this idea, bringing classical themes with a modern twist to each character, or “master” that the player chooses. My favorite, though, abandons classical music and aims for a bizarre, chaotic dubstep track for character Jimmy Lightning. More remarkable than the music itself is the careful integration of the music into the game—with each peg being a note that harmonizes with the theme for the level.

Beep video clip: Guy Whitmore tells us all about the musical choices in selecting and creating the music for Peggle 2. The interview was recorded in Vancouver in August 2015.

References

Behemog. (2016, February 25). Wild Arms – Ps1 Soundtrack 2-20 – A Lonely Dream of Bygone Days. [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6dpm1s9_f3U

BioShock, 2K Games, 2007.

Castlevania: Harmony of Dissonance, Konami, 2002.

Collins, K. (2006). “Flat Twos and the Musical Aesthetic of the Atari VCS”. Popular Musicology Online. Issue 1: Musicological Critiques. Retrieved From: http://www.popular-musicology-online.com

Collins, K. (2008). Game Sound: An Introduction to the History, Theory and Practice of Video Game Music and Sound Design. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Collins, K. (2016). The Beep Book: A Documentary History of Game Sound. Waterloo, ON: Ehtonal, Inc.

Dante’s Inferno, Electronic Arts, 2010.

DerSchmu (2010, December 16). NES Longplay – Metroid (100% + best endsequence). [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ly1PUEmxyyQ

DerSchmu (2010, November 11). C64 Longplay – Monty On The Run. [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jAyDCti2XAc

Destroy All Humans! Pandemic Studios, 2005.

Deus Ex, Square Enix, 2000.

DigDug, Namco, 1982.

Doctormario4600 (2014, December 28). Mario & Luigi: Partners in Time Longplay [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OI2T744kCHw

Ehtonal, Inc. (2016) Beep: A Documentary History of Game Sound. BluRay.

Floppy Frenzy, Windmill Software, 1982.

Grim Fandango, LucasArts, 1998.

Highretrogamelord (2010, July 29). Tapeworm for the Atari 2600. [Video file]. Retrieved from

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rVFvlJ98Fu4

Inverse Phase (2012) Pretty Eight Machine. CD.

Kingdom Hearts, Square, 2002.

Legend of Zelda Ocarina of Time, Nintendo, 1998.

Mario and Luigi: Partners in Time, Nintendo, 2005.

Metroid, Nintendo, 1986.

Monkey Island 2: LeChuck’s Revenge, LucasArts, 1991.

Monty on the Run, Gremlin Graphics, 1985.

MrBlockzGaming (2014, July 3). BioShock Gameplay Walkthrough Part 1 – Welcome To Rapture (No Commentary) [PC]. [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5OC15R2XYBg

Nolddor, Jack. (2012, December 28). [Full GamePlay] Shadow of the Beast [Sega Megadrive/Genesis]. [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vOw8TzvZa9g

Peggle 2, PopCap, 2014.

Peggle, PopCap, 2007.

Pong, Atari, 1971.

SevuhnEluvuhn. (2013, March 1). Full Game Ocarina of Time N64. [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3QvlxoX1GjI

Shadow of the Beast, Psygnosis, 1989.

Sly DC (2015, March 4). Coleco Telstar Alpha – Tennis (AY-3-8500-1). [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1We3V-vFWAU

Squakenet (2015, March 14). Floppy Frenzy gameplay (PC Game, 1982). [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kx7aZ0YHFwA

Street Fighter 2: The World Warrior, Capcom, 1991.

Super Mario Bros, Nintendo 1985.

Tapeworm, Spectravision, 1982.

The Adventure Gamer (2014, August 19). Grim Fandango – Full Longplay [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kcqj0APsDsM

TheWalkthroughGuru (2013, December 9). Peggle 2 Xbox One Walkthrough Part 1 No Commentary Bjorn The Unicorn. [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8NjQ6jMasoQ

Tomb Raider, Eidos, 1996.

Unreal, Epic Megagames, 1998.

Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? Brøderbund, 1985.

Wild Arms, MediaVision/Sony, 1996.

World of Longplays (2010, November 5). Game Boy Advance Longplay [020] Castlevania Harmony of Dissonance [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=siIAivGSySs

World of Longplays. (2009, July 7). PSX Longplay [019] Tomb Raider (Part 1 of 3). [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LCO8R_qZ-cA

World of Longplays. (2009, March 20). PC Longplay [030] Monkey Island 2: LeChuck’s Revenge. [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tBNJgXcG1y4|

Author’s Info:

Karen Collins is Associate Professor in the Digital Arts Communication program at the University of Waterloo, Canada. She has published five books on game sound, including Game Sound (MIT Press 2008), From Pac-Man to Pop Music (Ashgate 2008), The Oxford Handbook of Interactive Audio (Oxford 2013), Playing With Sound (MIT Press 2013) and the 2-volume Beep Book (Ehtonal 2016). She is also the director of the award-winning game audio documentary Beep: A Documentary History of Game Sound (Beepmovie.com).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.