Frans Mäyrä (Tampere University)

Abstract

This article explores the early history (and even some prehistory) of game studies from a perspective that is informed by an analysis of claimed opposition between “objective” and “politically committed” research. There is a well-documented and long intellectual history of fundamental disagreements that have set apart the various idealist, rationalist, positivist, empiricist, and constructivist orientations in academia, for example. However, the contemporary climate of “culture wars” has surrounded such disputes with a novel, often toxic framing that aggravates confrontations and erodes possibilities for reaching agreement. This article tracks the charged prehistory of contemporary game studies on one hand into the rise of poststructuralism and the “theory wars” of 1970s and 1980s, and then moves to discuss the heritage of literary studies for game studies. The special emphasis is put on formalism as a strategy of manufacturing authority and objectivity for arts and humanities-based disciplines. The key argument in the article is that this history of intellectual warfare hides from us an alternative history – a dialectical one, which has quietly grown to become arguably the mainstream of (cultural) game studies today. Rather than isolating the formal and cultural, or aesthetic and political dimensions of game cultural agency and meaning making, the examples discussed at the end of article point towards the strategic value produced by such a dialectic approach for game studies.

Introduction: The Early Debate

One of the hotly contested areas in the contemporary climate of culture wars is located where different conceptions of “objectivity” and “politically committed research” clash. In game studies, the ongoing conflicts have been perhaps more openly available and more escalated than in some other fields of art and culture studies – for multiple historical reasons. This article is part of an ongoing effort to unravel some of the underlying roots and genealogy of current conflicts, and also to make a case for a certain kind of dialectic that could open productive directions for this field. As such, the argumentation may not appear immediately relevant to the contemporary study of games, but I feel that we need to capture this bigger picture, before dealing with more specific contemporary issues. It should be noted that this exploration is indeed a work in progress; at this point the emphasis is on historical contextualisation of some key developments in intellectual landscape that have had major impact on the emergence of ‘game culture studies’ as a certain kind of orientation in the wider field of game studies. The dialectic described in this article is provides also a rationale for the establishment of The Centre of Excellence in Game Culture Studies in Finland, and the particular conception of game studies that it embodies; this will be discussed in the final part of the article.

The overarching argument underlying this inquiry is based on view that while there has been multiple veins of intellectual history that have contributed into the apparently fundamental separation and opposition between elements such as ‘gameplay’ and ‘narrative’ or ‘representation’, the construction of such opposition is based on limited perspectives and has been detrimental for the development of game studies. The “alternative history” put forward this article is aimed at overcoming this kind of historical splintering – and as such can be seen as complementary to some recent efforts, such as the feminist and affect theory approach (see e.g. Anable, 2018) aiming to bring more coherence and unity in game studies. Hopefully, this account can also suggest why it should no longer be a “taboo” to speak about fundamental differences underlying the contemporary game studies; rather, such excavations should be seen as necessary, and therapeutic.

Starting from a wider look at this landscape, it is obvious that while attacks against politically committed or ‘progressive’ or ‘leftist’ intellectuals are particularly known from the North American and English-speaking context, there are also European countries – such as Poland – where gender studies or feminism in particular have been put under particularly large-scale conservative attacks (Graff, 2014). For feminist scholars studying games, the everyday reality has for a long time been one that includes denigration, attacks, and rape threats. Like Mia Consalvo writes, each such incident is troubling enough when taken in isolation, but when linked together into a timeline “demonstrates how the individual links are not actually isolated incidents at all but illustrate a pattern of a misogynistic gamer culture and patriarchal privilege attempting to (re)assert its position” (Consalvo, 2012).

It is a regular element in the rhetoric of right-wing activists and political conservatives in particular to attack the reliability and value of scientific research on grounds of academics being blinded or biased due to their political affiliations or sympathies. There is even evidence that among certain circles “there is a palpable hostility toward the basic concept of higher education, as if college attendance made one part of a liberal conspiracy, and professors have come to be viewed as the embodiment of what many resent in American culture: political correctness, diversity, willingness to look to science for answers, secularism, feminism, intellectualism, socialism, and a host of other ‘isms’” (Cuevas, 2018).

There are probably at least dual notable main roots in this debate, but they often become confused in the academic context. One is academic, the other one political and populist. The academic side of the discussion has focused on themes that are often categorised under the scientific realism (and “positivism”) versus social constructionism themes. The aggressive, politically loaded tone this old debate has taken, however, is somewhat novel. The epistemological roots of the disagreement go deep in the history of thought. It is useful to remember how the classic positions were formulated in this context. Already Plato saw human capacity for real knowledge as limited, as his famous cave metaphor also underlines (The Republic, Book 7). As an “Idealist”, Plato thought that everything that we base on our empirical observations – the world of senses – is not producing real knowledge, just opinions. Only the timeless forms or the world of Ideas is the domain of universal and true knowledge. In contrast, Aristotle can be positioned as an early “Empiricist” thinker, who did not believe in the innate world of pure forms or ideas, but rather emphasised that people arrive a bit like empty slates when born, and can construct knowledge and concepts about the surrounding reality only through experience, observation and interaction with the world (Aristotle, On the Soul).

The philosophical divide or opposition between idealism and empiricism has taken many forms since, including the tradition of philosophical “rationalism”, which holds that one should not trust senses but rather rely on logic to find truth. And on the other hand, following Aristotle to the birth of modern empirical sciences, there is the tradition of empiricism, which holds that all we know is gained through experience, and that careful testing and observing can improve our knowledge. In the field of game studies, one could position formalist and empirical approaches to the study of games and play as inheritors of this classical dualism.

The reference to the classical opposition about the epistemological fundamentals is not in itself enough to explain the politically charged undertones that face the academics working today. The intellectual and political developments that took place during the twentieth century are also something that should be taken into account, including also several traumatic historical episodes, including the legacies of multiple world wars, holocaust, colonialism, slavery, and struggles of conflicting political systems taking place within the worsening ecological catastrophe in a global scale. Some of the crucial steps in the development of the intellectual conflict underlying the contemporary game studies emerged during the 1980s and 1990s. It was during this time when the so-called “theory wars” took their current direction. There is an acknowledged, special relationship between literary studies and game studies’ emergence (see e.g. Aarseth, 1997; Murray, 1997; Egenfeldt-Nielsen, Smith & Tosca, 2008; Mäyrä, 2008), and it was literary theory which was perceived to be at the cutting edge in development of new theoretical discourses and approaches in the 1980s. Drawing from earlier, 1960s and 1970s poststructuralist thought particularly in France, the American translations, discussions and adaptations developed the thought of Jacques Lacan into “Lacanianism”, and writings of Jacques Derrida into “deconstructionism”, for example. While bearing witness to the impact of such “continental thought” on wider international audiences, the growing popularity of such, theoretically and conceptually complex approaches also faced increasing resistance and provided some of the foundation for later conservative attacks on what they would call “postmodernism”. The role of this moment of history for the present discussion of game studies is crucial, as it represents an important moment of awakening into more nuanced self-awareness in human sciences – and one that would later underlie the epistemological-political tensions that would charge the landscape of early game studies.

Fundamental Differences: Derrida and Searle

The conflict that emerged in the early 1970s between Derrida and John R. Searle, an American analytical philosopher, is indicative of the future of such “theory wars”. To summarise the complex debate to what I consider to be its core issue, Derrida was both praising the Anglo-American “speech act theory” (initiated by John L. Austin in the 1950s) in expanding our understanding of the effects of language on our thought and relationships with the reality, but also criticizing the approach for a limited and “normative” view on how language operates. As is typical for Derrida’s strategy, he emphasises the impossibility of using language precisely, as there are always surprising and unintended effects to all expressions – which is particularly central in artistic and fictional contexts of language use, which Austin had described as “parasitic” and non-serious and thereby something to be excluded from any consideration in his language and communication theory (Derrida, 1988, p. 19 [orig. 1971]). John R. Searle published a response to Derrida in 1977, basically arguing that any, even written reproductions of oral speech acts still retain their link with the intention, and thereby their authority and force – as is evidenced by a priest pronouncing two people as “husband and wife” – is real; or, as Searle writes “there is no getting away from intentionality, because a meaningful sentence is just a standing possibility of the corresponding (intentional) speech act” (ibid, p. 26). While both philosophers come out of the debate as genuinely interested in “How to Do Things with Words” (the title of Austin’s famous posthumous 1962 book on speech act theory), they were fighting for different priorities and different strategic and political consequences for philosophy. As it is likely that there is always both an element for misunderstanding and play, as well as an element of real-world power in any use of language, it appears that both philosophers are committing a bit of violence towards this complexity, in order to make their points. And this intellectual violence is exactly what Derrida directly addresses in the “Afterword” to Limited Inc (the 1988 edition collecting most of this debate in a book form):

The violence, political or otherwise, at work in academic discussions or in intellectual discussions generally, must be acknowledged. In saying this I am not advocating that such violence be unleashed or simply accepted. I am above all asking that we try to recognize and analyze it as best we can in its various forms: obvious or disguised, institutional or individual, literal or metaphoric, candid or hypocritical, in good or guilty conscience. And if, as I believe, violence remains in fact (almost) ineradicable, its analysis and the most refined, ingenious account of its conditions will be the least violent gestures, perhaps even nonviolent, and in any case those which contribute most to transforming the legal-ethical-political rules: in the university and outside the university. (Derrida, 1988, p. 112.)

It is in such ethical grey areas, strategies, and in the political consequences of science, scholarship and “theory” where the important differences and significance of this conflict for the current discussion can be identified. While both Derrida and Searle can be positioned as late modern thinkers in how they both appear as highly aware of how language, words and the structures of culture we remain embedded into, will always affect the manner in which we exist and act in the world, they perceive the responsibility and accountability of academics differently. In carrying out his work in “weak social constructionism”, Searle (1997) focuses on the structure of social and institutional facts, and how such social facts make certain statements true, or not. As such, if taken as an “apolitical”, disinterested or liberal science and scholarship project, such approaches may also be turned into effective use by various authorities of institutional power – a fundamental characteristic of any form of “disinterested” science and scholarship.

The tactic of Derrida and other “poststructuralist” thinkers is different, as their strongest contributions can most often found in the manner how they question any claims of objectivity and neutrality and highlight how various socio-historical or textual contexts have an effect on how such “power discourses” operate. As such, they might be less useful in unravelling the “reality” of things, but more helpful in strategic efforts to question and change such realities – in educating us to improve our critical mindset. It could be claimed that perhaps the most significant weakness of the poststructuralist, high theory discourse in its utmost form relates to the love for convoluted language and apparently over-complex argumentation, which is often evident in some of these fields. While this way of writing might be tactically useful in providing emerging young fields the shield of intellectual rigor and a “place of its own” in academic discursive landscape, it also makes such forms of scholarship vulnerable targets for malicious attacks, such as the infamous “Sokal experiment”. This was a publication hoax carried out by Alan Sokal, a physics professor by submitting a nonsensical, jargon-filled paper into Social Text journal, and getting it published in 1996. Similar attacks (or, if more playfully taken, “trolling projects”) have been carried out afterwards against cultural, queer and gender studies, for example (see “The Grievance Studies affair”, a hoax paper project created by Helen Pluckrose, James A. Lindsay and Peter Boghossian; Schuessler, 2018). It is worth noting an interesting deconstructive reading of the “Sokal Affair” in this context: in her analysis, Clare Birchall (2004) suggests that there actually exists a largely unexplored productive interpretation of these kinds of wilful offensives; that it is possible to produce sense as well as nonsense from this kind of text actually demonstrates in practice the power of many poststructuralist arguments about the undecidability around legitimacy and knowledge. Rather than restoring everyone’s faith in the final authority of science and fundamental truths, this kind of hoax studies can be used to spread awareness and highlight how the production of knowledge rests on a particular kind of system involving trust and authority – and how such systems of knowledge production can rather easily be broken. In a late modern (or, postmodern) condition, the “discursive authority” can always be questioned, thus also motivating the postmodernist strategies of writing in a manner that is always sous rature – under erasure (which is, in Birchall’s sense, a necessarily paranoid, political strategy).

While it can be argued that Derrida and deconstruction as a project, or strategy, has had certain political consequences or stances (see McQuillan, 2007), this field of scholarship has favoured complex and critical argumentation that appears most suitable for application in exposing contradictions and “aporias” in all systems of thought, rather than being positively committed for any single cause. On the other hand, the legacy of another Frenchman, Michel Foucault, has been particularly central for analyses of power, discourse, agency and body – all central concerns also for game studies, when the research perspective is opened to take into account questions of gender, ethnicity and inequality in societal and global scale. If the traditional continuation of the Enlightenment project in (“progressive”) academia for a long time relied on Marx and Marxist thought (putting emphasis on class, economic power and, on those grounds, to solidarity towards oppressed and suppressed voices), Foucault both complicated matters and also opened up new directions for critical inquiry. While being suspicious towards traditional political movements (young Foucault had his negative experiences in a Stalinist-style communist party), Foucault carried out historically and philosophically informed analyses that complicated the traditional picture of power as merely repressive, authoritarian element in culture and society. Rather, Foucault emphasises that development of modern societies has also meant internalisation of various techniques of social regulation and control, to the degree that the awareness of perpetual “surveillance” is internalised by individuals to produce self-awareness in manner that is essential for the modern subject (Foucault, 1995). In addition, he continued to analyse the construction of social reality and agency through various forms of “disciplinary power” and “bio-power” (Foucault, 1990) – arguing that the “exercise of power perpetually creates knowledge and, conversely, knowledge constantly induces effects of power” (Foucault, 1980, p. 52). Foucault particularly warned that “modern humanism” is mistaken in “drawing this line between knowledge and power” (ibid.). This can be seen as a comment directed towards more Idealist (or: Rationalist) style projects that see themselves as apolitical pursuits for neutral and objectively verifiable kind of knowledge. The legacy of this tensioned phase on late modern scholarship can be further analysed next with a look into the early stages of emerging game studies.

The Birth Pains of Game Studies

There are multiple roots underlying the rise of contemporary game studies (as witnessed, e.g. by the opening issues of journals Game Studies in 2001, and Games and Culture in 2006), and looking back at the above discussion, it can be said that the new research field or emergent discipline (depending on perspective) was born into a charged academic landscape. On one hand, it was faced with the considerable existential struggle of both proving that (digital, computer, video, mobile, etc.) games were a valuable topic, or a “serious” area for scholarship, worthy of investment of time and resources. One argument that was often used at this point was to make reference to the considerable economic significance of games as a field of digital content industry; also, the demographic and behavioural shift was highlighted as a reason to invest into the new, game studies discipline: hundreds of millions of people had started playing these new kinds of games (e.g. Aarseth, 2001). At the same time, academics were entering this new field from some older, established disciplines, and the study of games remained surrounded – and possibly in the end was destined to be assimilated – by other fields (Aarseth, 2001; Deterding, 2017). The infamous “ludology vs. narratology debate” (Frasca, 2003) was then an early instance when the views about the direction and “content” of this field being contested. Thus, the struggle at the “external boundaries” in the field definition are to a certain degree mirrored in struggles on “boundaries / division lines within” the field. In a rather Foucauldian turn of events, it was this “biopolitics of definitional debate” that has served as a sort of educational tool, focusing on what kind of ontological and epistemological claims the game studies as a field or discipline is based on, what are its proper subjects of study, correct methodologies, and who is able to define such fundamentals. For example, in her response to Frasca’s account of the “Debate”, Celia Pearce (2005) objects to the act of naming such “two camps”: “The very act of bestowing the suffix ‘-ist’ is a kind of spell-casting exercise that only serves to reinforce the so-called false polarity that Frasca attempts to critique”. It would be relatively easy to pass on the entire debate on one hand, and the requests to return into a boundary-free state of game studies on the other, if this conflict would not be potentially unearthing some deeper conflicts within the “game studies project”.

Patrick Crogan was one among few scholars who were writing early critiques of ‘ludology’, suggesting that while there is certain analytical value in the ludological approach, in its “purist” form it is also deeply problematic in narrowing down the subject of study in what could even be considered a nonsensical manner. Crogan (2004) points towards the early work by Markku Eskelinen, Jesper Juul and Espen Aarseth in particular. More recently, Tom Apperley (2019) for example has argued that game studies’ focus and attention on ludology (in the shape of “ludology vs. narratology debate”) is even harmful: there is an “unarticulated anti-theory stance of ludology”, which means that entering the field of game studies through this angle will also expose young scholars to ways of thinking that are hostile to feminist theory specifically. It is worth pausing to reflect, why this would be the case – and what would game studies be without central attention and scholarly focus put on ludology, in particular? In the context of this discussion, it is worth considering the early ludological approaches as a certain kind of narrowly formalist exercise – that also comes with the long history of formalist claims for power as well as for scientific or scholarly authority. As many early “ludologists” were trained in literary studies, and in literary theory, we can take our lead from the longer history of how that field (or discipline) evolved, while featuring certain similar tensions and tendencies in relation to formalism.

Formalism: The Heritage of Literary Studies

While there are elements in contemporary critical thought in literary and textual theories that go all the way back to Aristotle’s Poetics, or the classical rhetoric teachings on “effective and persuasive communication” (studies of tropes, or figures of speech, for example), much of the stage for modern criticism was set in the early decades of the twentieth century. While the traditional style of scholarship that focused on analyses of different kinds of texts was scattered in multiple directions of the evolving, early modern academia, a large part of these traditional approaches was rooted in philological studies of words and comparisons of different text versions, and in the history of “great men” style biographies. The early formalist approaches – the “New Criticism” movement in particular – rebelled against this, arguing for more sophisticated and scientific methodology to study literature as works of arts, rather than as extensions of a person in the biographical style. New Criticism is commonly known for putting emphasis on “close reading” as a careful unravelling of complex poetic devices, while aiming to understand works of art as autonomous wholes.

Another aspect of this movement was the rejection of authorial intention, which American scholars William K. Wimsatt and Monroe Beardsley popularised in their article “The Intentional Fallacy” (1946; note that this has an interesting parallel in the “death of the author” discussion, initiated in France in the 1960s, see Barthes, 1978). It is the text and form itself which should be the source of meaning, not the thoughts, lives or ambitions of the original author. The complementary version of this idea was titled “Affective Fallacy” (also discussed in an article by the same authors; Wimsatt & Beardsley, 1949). To quote: “The Affective Fallacy is a confusion between the poem and its results (what it is and what it does), a special case of epistemological skepticism […which…] begins by trying to derive the standard of criticism from the psychological effects of the poem and ends in impressionism and relativism [with the result that] the poem itself, as an object of specifically critical judgment, tends to disappear” (ibid., p. 31). Thus, for formalist approaches, neither the author or the reader/user of the text matters – only the “pure” text or work of art itself. This separation of text from contextual conditions for meaning making, and from experiential, historical and bodily realities of real human beings is something that several non-formalist approaches rose to question in the latter parts of twentieth century.

Formalism became the de facto reigning philosophy that underlined many strands of humanities-based scholarship during most of twentieth century – arguably from hermeneutics to structuralism and to deconstruction(ism; e.g. Culler, 2008). One could perhaps suggest certain kind of trauma or unresolved ambiguity that derives from the accusations of impressionism or of being guilty of overtly-emotional, subjective criticism in literary and art studies, as being part of the reason why these fields in academia have been driven toward direction that is arguably the closest counterpart of “hard science” we can find in the domain filled by human meanings and relational negotiations of signification. Though, one should note that as a general trend the move towards formalism can also be rooted in the increased professionalism and specialisation of science and scholarship: there are institutional and structural reasons why academia is generally tilted towards formal and seemingly neutral “systemic” approaches (e.g. O’Neill, 1992).

If we interpret early ludology as the formalist version of game studies, we can set within a certain kind of interpretative framework also such extreme claims as this often quoted one by Markku Eskelinen:

The old and new game components, their dynamic combination and distribution, the registers, the necessary manipulation of temporal, causal, spatial and functional relations and properties not to mention the rules and the goals and the lack of audience should suffice to set games and the gaming situation apart from narrative and drama, and to annihilate for good the discussion of games as stories, narratives or cinema. In this scenario stories are just uninteresting ornaments or gift-wrappings to games, and laying any emphasis on studying these kinds of marketing tools is just a waste of time and energy. It’s no wonder gaming mechanisms are suffering from slow or even lethargic states of development, as they are constantly and intentionally confused with narrative or dramatic or cinematic mechanisms. (Eskelinen, 2001.)

As an author and a literary theory educated scholar in particular, Markku Eskelinen is here effectively arguing for formalist criticism that is focused on studying the “essential form” of games in the “mechanisms of gaming”, while simultaneously promoting rejection of those elements of game form that are already studied by established disciplines – as for example in the case of games’ storytelling dimensions, which is a topic area that can to a certain degree addressed from perspectives opened up by literary, media, drama and film studies. However, in the above quote there is also an interesting implied extension of the “ornaments” or “gift-wrappings” into everything that is not a part of (formal) “game components”, that would in the future discussions take the purist position of ludology even further.

This move is related to another notable moment in the early days of modern game studies, where the abandoning of storytelling dimension of games was extended to the visual or representational aspects of games. Furthermore, the shape this “rejection of representation” argument took is politically highly symptomatic, particularly when analysed through the “(female) body does not matter in games” argument as made by Aarseth:

The ‘royal’ theme of the traditional pieces is all but irrelevant to our understanding of chess. Likewise, the dimensions of Lara Croft’s body, already analyzed to death by film theorists, are irrelevant to me as a player, because a different-looking body would not make me play differently […]. When I play, I don’t even see her body, but see thorough it and past it. […] It follows that games are not intertextual either; games are self-contained. (Aarseth, 2004, p. 48.)

It should be noted that Aarseth was by no means alone in arguing for a “non-representational focus” for early game studies. A similar argument was made for example earlier by James Newman (2002), who argued that while playing video games, “appearances do not matter” as “the pleasures of videogame play are not principally visual, but rather are kinaesthetic.”

A decade later, Esther MacCallum-Stewart (2014) commented on Aarseth’s claims in an article published in the Game Studies journal, paying attention to the political and gendered manner of representation’s exclusion:

Here, it is the seeing in order to unsee that is important, as Aarseth chooses Lara to make this point, rather than a masculine or gender-neutral target. Aarseth’s argument would not have the same impact were it to contain the name of Max Payne, Bioshock Infinite’s Booker (Irrational Games 2013), or Trevor Philips from GTAV (Rockstar, 2013) (who spends a vast percentage of the game without a shirt on, often resetting to this default despite previous scenes where the player has chosen to clothe him) inserted instead. Drawing attention to Lara as immaterial simultaneously points to her irrefutable position as a woman already considered out of place. This is supported by the continuing attention given to female protagonists, who are still usually introduced in a fanfare of novelty, and often highly scrutinised for their suitability within the games industry. (MacCallum-Stewart, 2014.)

Already in the context of the original (interactive) First Person book project, Stuart Moulthrop had reacted to Aarseth’s claims and warned against cutting off the study of game from the study of their cultural contexts, saying that one would only end up with a sterile, dogmatic discipline. In a way, Aarseth during online dialogue actually agreed with this warning, but also stated (in his online response) that while one would be a “fool” – or a “fundamentalist” – to disagree with Moulthrop, he also claimed: “But fundamentalism has its uses. In academic discourse, a clear, uncompromising, radically different position can be invaluable simply by forcing the rest of the field to do more critical thinking” (Aarseth, 2004 1). While congratulating ludologists on creating debate, Patrick Crogan (2004) titled this strategy in his discussion under an ambiguous heading of “theory game” – a concept which he did not take further in his discussion, but which can even imply that a purist position involves a potentially ethically questionable element of “playing games” with the academic community or its academic standards.

This is a crucial point when we are discussing the commitments and underlying aims of game studies. Taken in a positive spirit, one could envision a ludological version of game studies as a playful, sometimes a bit trolling, or “unserious discipline” (as in Simon, 2017). However, like Audrey Anable (2018) and others have claimed, when initial game studies was built on the formalist opposition between rules and representation, with dominance of the former dimension, it was also left “ill equipped to address issues like racism, homophobia and misogyny in video games and gaming culture” (ibid., p. xvi). Importantly, formalism was also not able to provide game scholars any solid foundation for responding to the #GamerGate attacks, as they moved to target feminist and cultural studies game scholars, in addition to female game designers, players, and game journalists (cf. Chess & Shaw, 2015; Mortensen, 2018).

The Politics of Teaching Game Studies

It is also worth having a moment of soul-searching at this point. I am myself an author of one of the textbooks in the field of game studies (Mäyrä, 2008), and the director of The Centre of Excellence of Game Culture Studies (2018-), and from this perspective it is important for me to ask firstly, how has game studies as applied in the education of students and in the creation of ambitious research structures been positioned towards the “purist” ludology position, as discussed above?

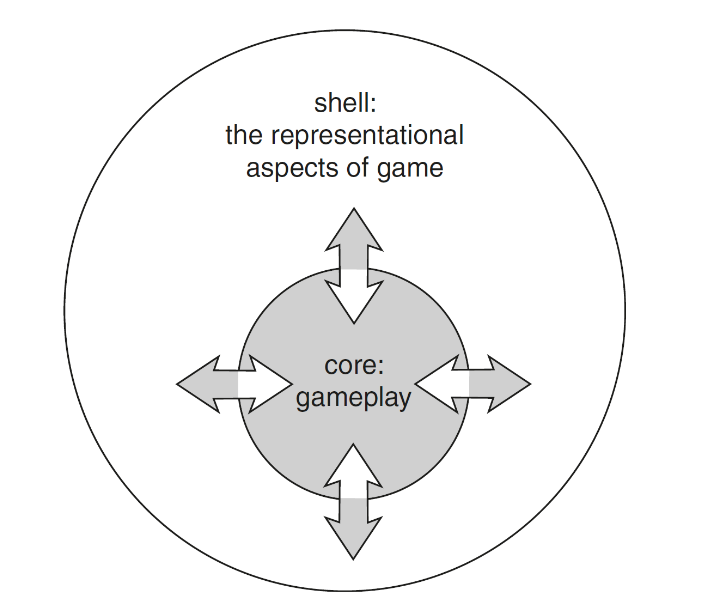

Looking back today at my early textbook, An Introduction to Game Studies: Games in Culture, I can see many points where I could have clarified particularly the practical consequences of certain theoretical choices. Also, the entire contemporary “culture wars” situation had not yet emerged (most of the book was originally written in 2006) in the shape and condition that later made so visible the consequences and political affiliations of certain cultural and analytical positions. For example, the ambiguous status of detailed digital representation as something that was both celebrated (as an evidence of digital games advancement) and strategically dismissed at the same time (when feminist critique highlighted the blatant sexism and stereotype-filled character of mainstream games and gaming) is something that, in hindsight, I could had dedicated much more thought in the book. Saying that, it is important to note that the basic position that I opened this book with, is one emphasising the situated and contextual character of meaning-making: we cannot erase the player, as the focus of game studies should be in the interaction between the game and the player (ibid., p. 2). I do discuss the question of analytically separating “gameplay” from “representation” in games, and for purposes of simplification (this is a textbook, after all) present the schematic illustration (see Figure 1, below).

Figure 1: “The dialectic of core and shell, or gameplay and representation in the basic structure of games” (Mäyrä, 2008, p. 18).

It could perhaps be interpreted as a politically questionable choice to set the gameplay as the “core” of games, as there are certainly game genres, styles of play, and players with preferences that clearly and strongly prioritize representational or storytelling dimensions of games over the dynamics of gameplay (which, in contrast, can also be minimal, non-challenging, or highly repetitive and uninteresting part of some games). The main intended message in the framework of this book was, however, to discuss how this “dialectic” or interplay between the representational aspects and gameplay dimensions is something that is essential to consider while addressing the “basic structure” of games. This interplay is also embedded in cultural, societal, economic and political frameworks to the degree that all studies of games should also be informed by studies of players, their (real-life) contexts, as well as by studies into the contexts of production and consumption of games – for studying games as culture (ibid., p. 2). This basic critical, dialectical and inclusive position is something that I am still happy to stand behind, also today. As the possibilities (and limitations) for identification and identity construction in gaming and regards to game characters was also discussed (ibid., pp. 69, 86, 107), one could say that if this one textbook would be a representative example (which I am not sure it is), then the “purist” ludological position would not be the one that has been dominantly adopted in game studies education. While the real state and evolution of game studies curricula in academia has not yet been comprehensively analysed, to my knowledge, it should be noted that such other early books as Rules of Play (Salen & Zimmerman, 2004), Understanding Video Games: The Essential Introduction (Egenfeldt-Nielsen, Smith & Tosca, 2008) and Perceiving Play (Mortensen, 2009), all of them also used in game studies education, do all in their different ways address the cultures surrounding games and play, thus by no means limiting game studies into the formalist analysis of “ludic forms”.

In spirit of dialogue and dialectic, one can then put forward the question whether all formal analysis is then suspect – of hiding some questionable (conservative) political agenda behind its objective-looking surface? It is indeed perfectly possible for politically active researchers to criticize their less-societally-active colleagues for not doing enough, and not being committed enough to make any real change in areas where inequality and social wrongs rule – thereby actually becoming “accomplices for the oppressors”. Positively taken, this kind of discipline-internal critiques can serve as valuable wakeup calls, and as invitation for further self-critical soul-searching: are we aware of our blind spots and biases? In the areas where the study of games and games in cultures intersect, this is a particularly important issue, since the tensions related to aesthetic forms and meaning production processes interact in these areas in a particularly powerful manner.

One classical objection to “mixing politics with science” is that a politically committed foundation for research will lead to bad science: the results are a pre-given starting point, rather than the neutral and objective final outcome, goes this argument. On the other hand, it is a part of the everyday reality of everyone who applies for research grants that the “impact” of research is presented as a key criterion for successful science and scholarship. The high-quality academic work is expected to directly engage with the surrounding society and help in some ways to solve the problems we are facing. In their article discussing the “academic/activist divide” Catherine Eschle and Bice Maiguashca (2006) quote Sara Bracke, an activist with European network NextGenderation, claiming that “the division between doing and thinking is very racialised and gendered […] and that has worked against women and ethnic minorities who are entreated to act in the name of revolutions which are thought through by white male others”. Bracke insists that “critical theoretical work is a crucial part of political work”, although “it can never replace the other kinds of political activities we need to be doing to transform social reality”. Some of the examples Eschle and Maiguashca feature from their own research with feminist anti-globalisation activists, working in locations such as India, point to the use of games as an effective means for bridging the divide from abstract thought into lived experience.

The Politics of Organising Games Research

When practical decisions about the direction of research are made today, the traditions of thought and debates discussed above will form some of the background for strategic decision-making: how can, or should, we study games, play, players and their applications in different cultures and societies? As suggested by the line of argument running through this article, there are multiple scholarly-political alternatives that have been open for conducting game studies, since early on, and largely derived from the intellectual roots of related academic approaches. When we make strategic decisions about doing game studies today, one could start by picking sides in a clear-cut manner in the polarised academic landscape, and thus avoid any potential internal conflicts or disharmony. The example of the establishment of The Centre of Excellence in Game Culture Studies (CoE-GameCult, 2018-), which I will discuss in the final part of this article, is based on a different, alternative strategy, and one that I believe is more productive for the field one in the long run.

In practical terms, one of the key research-political questions for establishing more sustained and large-scale research efforts in the academic field of games and play studies (or indeed any field) is funding. The question of funding is then related to the institutional structures and mechanisms that facilitate scientific and scholarly work. Under the broader international trend of funding cuts hurting the university sector (cf. Oliff et al., 2013), there are limited opportunities for establishing a new academic discipline, such as game studies, without simultaneously cutting down resources of some other, established fields. It is also important to acknowledge that fundamental or basic research, and applied research are also differently situated in this kind of tensioned environment. While fundamental research is based on the rationale of expanding the field knowledge, without any immediate promises of commercial exploitation, the applied research can claim to have much more direct links to the short-term economic needs of society or industry.

There were specific opportunities and threats facing the study of games in the late 1990s and early 2000s academic environment, and I have described some of the operations and strategies we applied at this time in Finland in earlier works (Mäyrä, 2009; 2017). One key strategy involved using applied research funding opportunities to simultaneously further some key theoretical and methodological, basic research interests, while also staying agile enough to regularly reorient the research to address interesting emerging phenomena, such as location-based gaming, the free-to-play business model, social (media) gaming and the various societal impacts of gaming. The aim to understand better the changing target – what games, play and game culture are, and mean, for different people – was the one constant, underlying imperative in this process.

One notable feature of such “agile” academic work is that it easily becomes highly multi- and interdisciplinary. Rather than being committed into any single theoretical tradition or even methodology, research of games, play and related societal and cultural phenomena can easily appear almost omnivorous. For example, in several of our Tampere University Game Research Lab early research projects and publications, the key concepts and research methods often featured a highly hybrid approached, derived from an intermixture of humanities based art studies, psychology of virtual environments, human-computer interaction (HCI), and several other academic fields, all set into a dialogue with some select ludology-inspired, games’ art-form related questions (Mäyrä, 2009, p. 322). This approach on the one hand allowed the language of game research to resonate with multiple academic, expert audiences, while the interdisciplinary approaches also contributed to wider applicability of research findings; we were addressing such topics as digital play in social contexts, gameplay immersion, violence and games, learning in games and money gaming, or gambling. There were thus multiple benefits derived by strategically interpreting academic game studies in a very wide and loose manner. At the same time, all genuine interdisciplinary work is based on dialogue, and this means also understanding and transparently acknowledging what one’s own, fundamental position is, in these kinds of dialogues. Game studies could not only continue as an “interdiscipline”, but it needed at least some unifying elements and continuities, in order to have a basis for accumulation of knowledge, and for implementing informed critique of its own project.

These earlier histories informed the design and fundamental goals of the Centre of Excellence in Game Culture Studies (CoE-GameCult), as it was established as a particular kind of site and environment of game studies. Together with my core team of colleagues – Raine Koskimaa, Olli Sotamaa, Jaakko Suominen – we created the Centre as a flexible and interdisciplinary site that should allow creativity, innovation and learning to take place. But we also wanted our Centre to have a clear enough focus, and an underlying philosophy and a mandate that would allow organic growth in certain, articulated and sustained directions. As such, the centre would be supportive of interdisciplinary dialogue and encourage diversity in game studies, yet also be founded on a particular vision of cultural game studies. This would be one that is informed by work done in formalist as well as non-formalist research traditions, and that would not play down the value of either empirical, real-world situated people engaged (or otherwise affected) by games and ludic elements in cultures and societies, nor those structural dimensions of games and play that can be uncovered by formal analytical approaches.

It should be highlighted that while based on principles of openness, respect and inclusivity for conducting research in multiple, fundamentally differing and maybe even incompatible ways, the strategic principle chosen for the Centre is dialectical, which goes beyond simple interdisciplinary dialogue or co-existence. A true dialectic process includes recognition of differences and engagement in a process where the initial conflicting positions are both elaborated and developed further, with an overall synthetic aim that does not aim to suppress conflicts but rather use them as dynamic drivers for change (McKeon, 1954).

In the case of CoE-GameCult research agenda, two overarching research questions were chosen, to facilitate creation of such dialectic: (1) What are the key processes and characteristics of meaning making that are significant for understanding changing game cultures? And (2) How is cultural agency being reshaped, redistributed and renegotiated in games and play, and in their associated societal contexts? These two broad questions (or, more appropriately, research agendas) were then further framed with the help of a particular version of the “circuits of culture” model (Johnson, 1986), which we adapted so it would support a comprehensive and analytically multidimensional game cultural research strategy. This would strategically connect with both the forms of games, practices of play and cultural contexts surrounding both of them, while also addressing societal structures of power, production and consumption – all aiming to create an environment with maximal amounts of potential contacts for researchers working with some specific aspect of this complex whole.

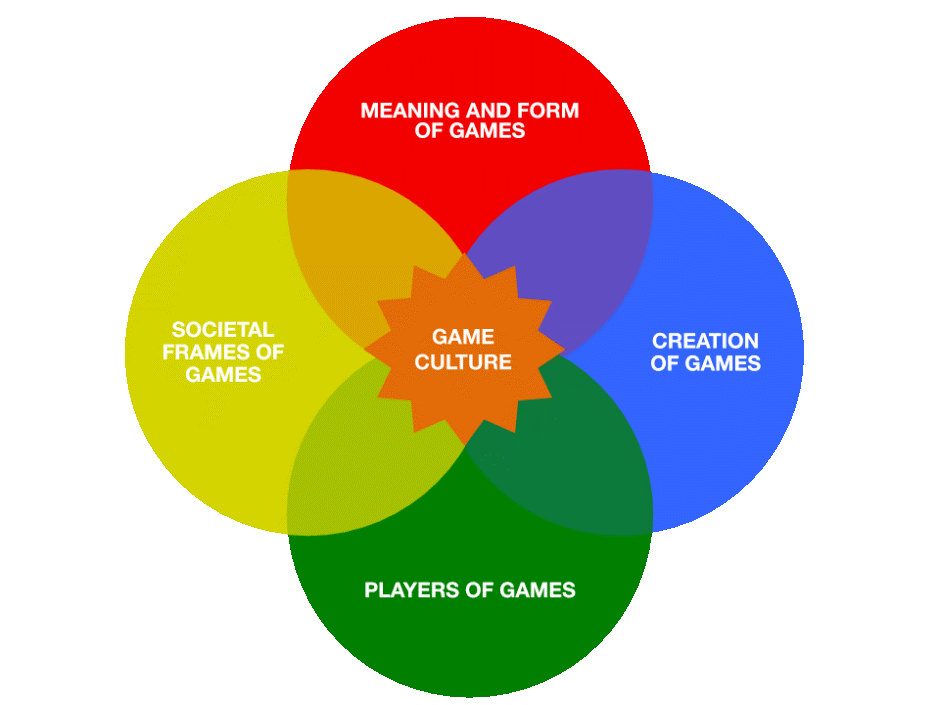

Consequently, we also did not want the Centre to be limited into any single type or aspect of games, but rather aimed at an environment that facilitates multiple interconnected studies that are informed by several interdependent moments in the “life cycle of a game”. When combined with the critical perspectives opened by inquiry into meaning making and agency, the four key thematic areas for study – creation of games, meaning and form of games, players of games, and the societal frames of games – are both specific and overlapping enough so that they direct the multiple research teams both to focus, specialize, as well as to better explicate the multidimensionality, complexity and various problems associated with contemporary games and their developing cultures (see Figure 2, below).

Figure 2: The organisational model of four key thematic research areas into the study of game cultures, in the Centre of Excellence in Game Culture Studies.

During the early years of Centre’s operations, the surrounding “culture wars” and “science wars” have probably rather aggravated than eased off. In Finland too, there have been Twitter wars and political campaigning that have put into question the “political bias” of academic research, and there has been demands for scholars to restrict themselves into conducting only neutral and “pure” science. It is a sign of the underlying confusion that the same conservative voices have also asked for academic research to be held accountable for the actual value and impact of public research money universities have been given. These populists do not appear to understand that such demands can be most efficiently answered by socially and politically informed and committed research, which is not “disinterested”, but rather strongly committed and engaged in improving the society. It should be noted that all major research funding organisations are today interested in such societal impact, and also our Centre of Excellence is expected to produce “Impact Narratives”, where we are required to outline the societally committed nature of our research work. Derived from analyses of emerging game cultural phenomena and their underlying tensions and power conflicts, the first period of work from the Centre has produced and reported efforts in following areas: inclusive game creation, exploring play in public spaces, examining (e)sports in relation to physical, mental, and social well-being, and promoting “demoscene” as intangible cultural heritage of humanity. Research in all these topics has involved multiple methodologies and contextual framings, rooted in understanding how both the expressive forms and real-world agency of variously empowered and disempowered people interact and contribute to situations and meanings in game cultures. This work has profited from perspectives opened by many pioneering works into “situated knowledges” and related critiques of simplified objectivity claims (e.g. Latour & Woolgar, 1986; Haraway, 1988).

Final Note: From Conflicts to Dialectics

The short historical overview presented in this article hopefully serves at least a dual purpose. Firstly, it is educational to notice that there has always been fundamental disagreements in how research should be conducted, what is valuable (or not) as a subject for research; it is just sad to note that the related disagreements are today perhaps even more aggravated and visible than before. Game studies has emerged into a charged intellectual and political landscape and is by no means immune to such fundamental disagreements and conflicts. Secondly, and on a more optimistic note, it should be said that there have all the time also been multiple ongoing efforts to build bridges between various opposing factions, and to learn from the interplay of diverse modes of inquiry. The above discussion about the Centre of Excellence in Game Culture Studies highlights a certain strategy for producing a multi-voiced, dynamic and dialectic environment for conducting cultural game studies, but this Centre is by no means alone in the pursuit of such goals. The dramatic oppositions, conflicts and war-derived metaphors are just too often getting disproportional amounts of attention in the historical analyses and synthetic overviews of the scholarly landscape. It is worth remembering that the dialectic between opposing views and coordination when faced by contradictions is a fundamental part of science and also a key philosophical method that has a long and sustained history, reaching to Hegel, Plato, and elsewhere (Maybee, 2019).

Finally, it is evident that the tension between more abstracted forms of intellectual formalism and the subjectively experienced and bodily situated meanings of games and play was addressed already at the very earliest stages of game studies and is thus informing its philosophical roots. It can be claimed that this conflict is even exactly the reason why already Friedrich Schiller, a German philosopher and poet, having experienced the consequences of such divide in the eighteenth century, developed his (“proto game studies”) theory of “play drive” to identify the area where our idealist and rationalist processes (“form drive”) and sensuous, emotional and bodily dimensions (“sense drive”) could be set into productive equilibrium. Schiller argues that being able to both be receptive of the world and also to liberate ones reason, a playing human will be able to have a twofold experience simultaneously, “when he was at once conscious of his freedom and sensible of his existence, when he at once felt himself as matter and came to know himself as spirit” (Schiller, 1796/2004, p. 73 [Letter XIV]). The final conclusion of Schiller was articulated in the famous dictum: “For, to declare it once and for all, Man plays only when he is in the full sense of the word a man, and he is only wholly Man when he is playing.” (Ibid., p. 80 [Letter XV]). It is both ironic and fitting that Schiller’s dated and gendered language carries an ethical and epistemological message that has perhaps its strongest contemporary heirs in the areas of feminist and queer game studies with their ambitious explorations on the affective, bodily and historical foundations of games and play in culture (e.g. in Anable, 2018; Ruberg & Shaw, 2017, and elsewhere).

Indeed, such ambition, bridge-building and synthetic vision is something that is also needed in the field of game studies today. When approached from the dialectic perspective promoted by this article, formalism and cultural or critical approaches into game studies are not actually “opposites” at all. Various forms of scholarship, like all human thought and practices come with implied or explicit political consequences or tendencies that can indeed be oppositional, but like the lessons in poststructuralist though have taught us, none such discourse remains completely under its authorial intentions as it operates in culture and society. Formalist tools of game analysis can very well be used (and have been used) to carry out feminist, queer or politically subversive readings of games. It is only when various approaches are kept in isolation, unaware of alternative perspectives, with their associated alternative experiences and values, when the limitations of such approaches start to aggravate.

The precept of dialectical game studies could be to remind us how no form of scholarship is an island – none of them are sufficient in themselves, but all of them can play their role in helping us to analyse, understand, and generate impactful ways to act on basis of that understanding. In the end, it should not be a taboo to say that we need theoretical and methodological work that not only acknowledges the multiple “knowledge interests” (Habermas, 1972) that are all relevant for game studies today, but also undertakes to carefully produce deeper, dialectic understanding from the conflicting and intersecting perspectives they open.

References

Aarseth, E. (1997). Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Aarseth, E. (2001). Editorial: computer game studies, Year One. Game Studies, 1(1). Retrieved from http://www.gamestudies.org/0101/editorial.html

Aarseth, E. (2004). Genre trouble, narrativism and the art of simulation. In N. Wardrip-Fruin & P. Harrigan (Eds.), First Person. New Media as Story, Performance and Game (pp. 45–55). Cambridge (MA): MIT Press.

Anable, A. (2018). Playing with Feelings: Video Games and Affect. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Apperley, T. (2019, March 26). On the persistence of game studies dull binary. Retrieved from https://critical-distance.com/amber/cache/e14dfa4228cef783d0f2c901ac08fcd5/

Barthes, R. (1978). The Death of the Author. In R. Barthes, Image-Music-Text (pp. 142-148). Trans. S. Heath. New York, NY: Hill and Wang.

Birchall, C. (2004). Just Because You’re Paranoid, Doesn’t Mean They’re Not Out to Get You. Culture Machine 6 (2004). Retrieved from https://culturemachine.net/deconstruction-is-in-cultural-studies/just-because-youre-paranoid-doesnt-mean-theyre-not-out-to-get-you/.

Chess, S. & Shaw, A. (2015). A Conspiracy of Fishes, or, How We Learned to Stop Worrying About #GamerGate and Embrace Hegemonic Masculinity. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 59(1):208–20.

Consalvo, M. (2012). Confronting toxic gamer culture: a challenge for feminist game studies scholars. Ada: A Journal of Gender, New Media, and Technology, (1). Retrieved from https://adanewmedia.org/2012/11/issue1-consalvo/

Crogan, P. (2004). The game thing: ludology and other theory games. Media International Australia Incorporating Culture and Policy, 110(1), 10–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X0411000104

Cuevas, J. A. (2018). A new reality? The Far Right’s use of cyberharassment against academics. Academe, 104(1). Retrieved from https://www.aaup.org/article/new-reality-far-rights-use-cyberharassment-against-academics

Derrida, J. (1988). Limited Inc (G. Graff, Ed.; J. Mehlman & S. Weber, Trans.). Evanston (IL): Northwestern University Press.

Deterding, S. (2017). The Pyrrhic victory of game studies: assessing the past, present, and future of interdisciplinary game research. Games and Culture, 12(6), 521–543. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412016665067

Culler, J. (2008). On Deconstruction: Theory and Criticism after Structuralism. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Egenfeldt-Nielsen, S., Smith, J. H., & Tosca, S. P. (2008). Understanding Video Games: The Essential Introduction. New York: Routledge.

Eschle, C., & Maiguashca, B. (2006). Bridging the activist-academic divide: feminist activism and the teaching of global politics. Millennium: Journal of International Studies, 35(1), 119–137. https://doi.org/10.1177/03058298060350011101

Eskelinen, M. (2001). The gaming situation. Game Studies, 1(1). Retrieved from http://www.gamestudies.org/0101/eskelinen/

Foucault, M. (1980). Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972-1977 (C. Gordon, Ed.). New York: Vintage.

Foucault, M. (1990). The History of Sexuality, Vol. 1: An Introduction (Reissue edition). New York: Vintage.

Foucault, M. (1995). Discipline & Punish: The Birth of the Prison (A. Sheridan, Trans.). New York: Vintage Books.

Frasca, G. (2003). Ludologists love stories, too: notes from a debate that never took place. Presented at the Proceedings of DiGRA 2003 Conference: Level Up, Utrecht. Retrieved from http://www.ludology.org/articles/frasca_levelUp2003.pdf

Graff, A. (2014). Report from the gender trenches: war against ‘genderism’ in Poland. European Journal of Women’s Studies, 21(4), 431–435. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350506814546091

Gross, P. R., & Levitt, N. (1997). Higher Superstition: The Academic Left and Its Quarrels with Science. Baltimore (MD): Johns Hopkins University Press.

Habermas, J. (1972). Knowledge & Human Interests. Boston: Beacon Press.

Haraway, D. (1988). Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective. Feminist Studies, 14(3), 575–599.

Johnson, R. (1986). What is cultural studies anyway? Social Text, 16, 38–80.

Latour, B., & Woolgar, S. (1986). Laboratory Life: The Construction of Scientific Facts. Princeton (NJ): Princeton University Press.

MacCallum-Stewart, E. (2014). “Take that, bitches!” Refiguring Lara Croft in feminist game narratives. Game Studies, 14(2). Retrieved from http://gamestudies.org/1402/articles/maccallumstewart

McKeon, R. (1954). Dialectic and Political Thought and Action. Ethics, 65(1), 1–33.

McQuillan, M. (Ed.). (2007). The Politics of Deconstruction: Jacques Derrida and the Other of Philosophy. London & Ann Arbor, MI: Pluto Press.

Maybee, J. E. (2019). Hegel’s dialectics. In E. N. Zalta (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2019 Edition). Retrieved from https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2019/entries/hegel-dialectics/

Mäyrä, F. (2008). An Introduction to Game Studies: Games in Culture. London & New York: Sage Publications.

Mäyrä, F. (2009). Getting into the game: doing multi-disciplinary game studies. In B. Perron and M. J. P. Wolf (Eds.), The Video Game Theory Reader 2 (pp. 313–29). New York: Routledge.

Mäyrä, F. (2017). Teaching game studies: experiences and lessons from Tampere. In Clash of Realities 2015/16: On the Art, Technology and Theory of Digital Games. Proceedings of the 6th and 7th Conference (pp. 235-241). Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag.

Mortensen, T. E. (2018). Anger, Fear, and Games: The Long Event of #GamerGate. Games and Culture, 13(8), 787–806.

Murray, J. H. (1997). Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace. New York: Free Press.

Newman, J. (2002). The myth of the ergodic videogame. Game Studies, 2(1). Retrieved from http://www.gamestudies.org/0102/newman/

Oliff, P., Palacios, V., Johnson, I., Leachman, M. (2013). Recent deep state higher education cuts may harm students and the economy for years to come. Retrieved from Center on Budget and Policy Priorities web site: http://www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=3927

O’Neill, J. (1992). Worlds Without Content: Against Formalism. London: Routledge.

Pearce, C. (2005). Theory wars: an argument against arguments in the so-called ludology/narratology debate. DiGRA’05 – Proceedings of the 2005 DiGRA International Conference: Changing Views: Worlds in Play. Retrieved from http://www.digra.org/wp-content/uploads/digital-library/06278.03452.pdf

Ruberg, B., & Shaw, A. (Eds.). (2017). Queer Game Studies. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Salen, K., & Zimmerman, E. (2004). Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals. Cambridge (MA): MIT Press.

Searle, J. R. (1997). The Construction of Social Reality. New York: Free Press.

Schiller, F. (2004). On the Aesthetic Education of Man (R. Snell, Trans.; Dover Books on Western Philosophy edition). Mineola (NY): Dover Publications.

Schuessler, J. (2018, October 4). Hoaxers slip breastaurants and dog-park sex into journals. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/04/arts/academic-journals-hoax.html

Simon, B. (2017). Unserious. Games and Culture 12(6):605–18.

Wimsatt, W. K., & Beardsley, M. C. (1946). The intentional fallacy. The Sewanee Review, 54(3), 468–488. Retrieved from JSTOR.

Wimsatt, W. K., & Beardsley, M. C. (1949). The affective fallacy. The Sewanee Review, 57(1), 31–55. Retrieved from JSTOR.

Author’s Info:

Frans Mäyrä

Tampere University

frans.mayra@tuni.fi

- See the online response at: https://electronicbookreview.com/essay/espen-aarseth-responds-in-turn/. ▲

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.