F. Peñate Domínguez (Universidad Complutense de Madrid)

Cover image: Bethesda Softworks/MachineGames (2014)

Abstract

This article addresses the use of “Nazi rock ‘n’ roll” in Wolfenstein: The New Order (2014) as a strategy to reinforce a historically selective sense of verisimilitude of the game’s dystopian setting. In W:TNO’s production, cover replicas of US popular music classics from the second half of the 20th century were composed in ‘Nazi mode’, with German themes and language, with the intent of creating a sense of stereotyped and mythicized knowledge of World War II that also imagined an outcome of the war in which the Nazis had won. The diegetic embedding of songs in this style could have supported the game’s atmosphere in a way that is comparable to the use of licensed works in games such as Grand Theft Auto and Fallout. However, the soundtrack composition was constrained by controversies around the representation of the Third Reich in computer games, a factor that also limited the role of the songs within the game world. The narrative potential of the original score thus remained untapped, as the songs were used mostly for marketing purposes. This paper highlights how music partly contributed to the creation of a myth-historical alternate timeline of post-WW2, and how the use of these songs could have turned the game’s story into a more complex and multifaceted discourse than what production allowed, contributing to a nuanced representation of Nazism, a theme that has remained controversial in the medium of the videogame.

Keywords: ludic-fictional worlds, historical video games, Nazism, myth, video game music, Wolfenstein.

Introduction

The video game Wolfenstein: The New Order (MachineGames/Bethesda Softworks, 2014) (W:TNO) addresses one of the most trendy counterfactual questions in contemporary popular culture: what if Germany had won World War II1? Despite the appeal of this hypothetical scenario, it is the first time veteran franchise Wolfenstein, known for its supernatural depictions of the conflict, explores this type of setting2, taking the series’ fictional universe to a whole new level. The sense of being trapped in a world where Hitler’s ideals are enforced using violence and coercion is not only produced through the representation of massive buildings that scrape the skies of “Neu Berlin”, or of the claustrophobic and labyrinthine sewers that members of the Resistance have turned into both their homes and headquarters; this sensation is also encouraged by the players’ explorations of the game levels’ visual and sonic features, as they discover more of W:TNO’s universe by reading newspapers clips that inform them about the capitulation of the globe before the Führer’s armies, or through the music that a new generation of “Germans” enjoy when listening to their futuristic record players. These seemingly secondary elements are key items in the credibility of a Nazi dystopia. As will be discussed, such elements act as remediators of popular narratives, especially about World War II 3, and are powerful tools in constructing specific understandings of the past. The discussion that follows will focus on the role that music plays in this process.

Besides an original soundtrack composed by Mick Gordon 4 that serves as the background music for the game, W:TNO features a tracklist made up from eleven songs edited and published by an imaginary, state-owned broadcast company called Neumond Records (New Moon Records). A list of the themes’ names and performers is shown below:

| Song name | Performer |

| “Berlin Boys and Stuttgart Girls” | Viktor and Die Volkalisten |

| “Toe the Line” | The Bunkers |

| “Mein Kleiner VW” | Hans |

| “Ich bin überall” | Schwarz-Rote Welle |

| “Weltraumsurfen” | The Comet Trails |

| “Zug nach Hamburg” | Die Schäferhunde |

| “Tapferer Kleiner Liebling” | Karl and Karla |

| “Mond, Mond, Ja, Ja” | Die Käfer |

| “House of the Rising Sun” | Wilbert Eckhart und seine Volksmusik Stars |

| “Boom! Boom!” | Ralph Becker |

| “Nowhere to run” | Die Partei Damen |

Source: Wolfenstein Wikia: “Neumond Records” http://wolfenstein.wikia.com/wiki/Neumond_Records, consulted 20/02/2016)

The appeal of the soundtrack resides in the apparent contradiction between its styles and its lyrics. Every artist is a parody of an American band or rock star from the 1950s and 1960s, “Nazified” to fit the game world’s dystopian atmosphere. For example, Die Käfer and Karl und Karla mimic The Beatles and Sonny and Cher, respectively. The Comet Tails with their song ‘Weltraumsurfen’ are referencing the emblematic surf-rock quintet The Beach Boys. Likewise, the song ‘Berlin Boys and Stuttgart Girls’ sounds awfully similar to the aforementioned band’s ‘California Girls’. In a similar way, ‘Zug nach Hamburg’, the greatest hit of the imaginary formation Die Schäferhunde is an almost direct reference to ‘Last Train to Clarksville’, by The Monkees. Finally, there are several licensed songs that have been modified to fit the game’s atmosphere: ‘Boom Boom’, by John Lee Hooker; ‘Nowhere to Run’, by Martha and the Vandellas; and ‘The House of the Rising Sun’, by The Animals. These hits work by adding an extra layer of authenticity and, at the same time, by generating a dissonance with sanctioned history intended to increase the appeal of the game world. However, in order to have a better insight of its ludic and fictional role in the game, we have to understand the process of creation and everything it implies: media conventions, potentials and culturally grounded limits. How does the soundtrack help build up the game’s setting? How did social and cultural conventions about historical computer games affect the production process of the musical score and its outcome? Did those conventions contribute to the whitewashing of a mythologized fantasy about yesterday’s Nazi-dominated tomorrow? The current paper aims to find answers to these questions through the use a specific methodological approach drawn from historical game studies, the contextualization of music in the game medium, and sanctioned discourses about World War II that are present in action games.

Theory and methodology

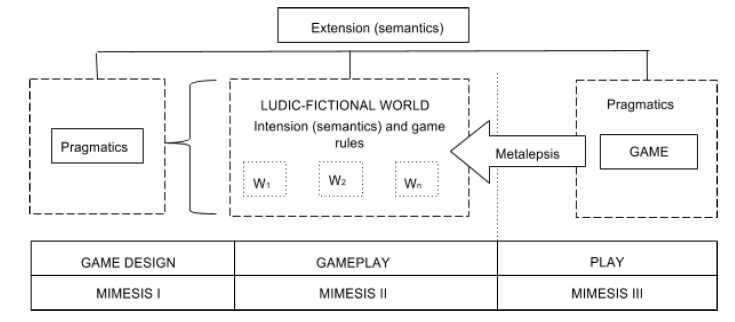

A game like W:TNO (or any other) is not an open window through which we can observe the past (which is inaccessible), or even sneak through in order to experience former events, but an interactive tool that remediates current worldviews, including those about the past, in its own unique way through all its elements: graphics, rules, narratives, and sound 5. Game scholar Antonio J. Planells de la Maza defines electronic entertainment products as “…complex fictional worlds that, as cultural artifacts, take part in a set of relationships inside current social, economic and political frames” (2015: 11). These worlds each have their own independent ontological status, which means that any of its elements are true unless they defy the inner logic and cohesion of said world (Planells de la Maza, 2015: 56-67). Although this definition attempts to surpass the classical, analytical theory of fictional worlds being just mimetic versions of our own reality, fictional worlds are constructed in the broader context of the real world. Thus, Planells (2015, p. 96) proposes a model to understand videogames that is very much influenced by Aristotle’s theory of mimesis 6, called the semantic-pragmatic model of the ludic-fictional worlds.

Planells de la Maza, A. J. (2015): Videojuegos y mundos de ficción: de Super Mario a Portal, Cátedra Signo e Imagen, p. 96. Translation by the Author.

According to Planells’ diagram, the creation and understanding of a game’s fictional world encompass three phases. While the first (game design) and third (play) are highly influenced by the context of the designer and player (pragmatics), the second one (gameplay) belongs to the realm of semantics 7. However, the three of them are connected by the extensional semantic, thus being related to each other and, ultimately, with their context (Planells de la Maza, 2015: 95-104). This sets a bridge between reality and fiction, which allows audiences to understand the imaginary world by filling the gaps with the logic and knowledge of their own world: this is called the principle of minimal departure by Ryan (1991: 48-60) and encyclopedic knowledge by Eco (1993: 38).

This principle allows authors and game designers, whether unconsciously or not, to avoid explaining general issues that are included in fiction, such as the composition of the human body or the law of gravity. More complex are the translations of specific personalities, groups, or elements with a strong and unique identity within the fictional text. In these cases, they are considered fictional particulars that are connected to their real references through an inter-world identity. A fictional particular, also known as replica and version, is the translation of a real particular (often a person) in a specific fictional world. Take, for example, Napoleon––the Corsican who lived between the 18th and 19th centuries is the real particular of the one featuring in War and Peace (Tolstoi, 1869) and also of the one Arno Dorian meets in Assassin’s Creed: Unity (Ubisoft, 2014). Replicas can share a number of properties with their originals, elements that make them recognizable by the audience and ultimately define their inter-world identity. However, these identities are flexible and malleable. According to non-existentialist semantics, the author has freedom in choosing to change the properties of the replica, altering its inter-world identity (Dolezel, 1999: 35-40). This is possible thanks to the ontological autonomy of the fictional world, which allows particulars within it to exist as long as they do not violate the world’s semantic logic. The same goes for the game I will examine in the following pages. Its music acts like a twisted replica of the sounds popularly identified as symbols of a particular era (the 1960s) that, despite the differences they present to their originals, still retain an identifiable inter-world identity.

Nevertheless, current research on historical fiction shows that replicas of historical categories need to share some particular elements with their originals to be credible. This makes their inter-world identity more rigid, to resonate better with audiences and become authentic. But what does it mean to a replica to be authentic? Elliott and Kapell believe that authenticity pursues fulfilling the audience’s historical knowledge and expectations, regardless of the empirical correctness of the replica. Seeking to create an inter-world identity based on real-world facts and data is not usually the aim of historical fiction, as an “accurate” translation of the past into the possible world (Elliott and Kapell, 2013: 359-361). Instead, the game’s historical signifiers are emptied and become loaded by myth 8.

Myth naturalizes and de-politicizes historical explanations; however, these narratives need to refer the past in order to be read as history. Video games achieve this through the strategies of selective authenticity, “…a form of narrative license, in which an interactive experience of the past blends historical representation with generic conventions and audience expectations” (Salvati & Bullinger, 2013: 154), often creating characteristic “brands” for each historical period 9. For example, authors focus on videogames set in World War II in order to identify the elements that, blended with genre conventions (in this case, first person shooters), configure BrandWW2. Accordingly, a game that features accurate representations of weapons and uniforms, manila folders, newsreel documentary and scenes inspired in movies and TV shows about the war is going to be accepted as a realistic historical simulation, regardless of the nature of its historical statements (Salvati and Bullinger, 2013: 157-164). This happens because the authentic feel of the fictional world strongly resonates with the player.

A historical resonance is the “recognition by the player of the game as ‘sufficiently’ real and related to a local context (shared history)” (Chapman, 2013: 35). These resonances come in multiple forms: image, text, narrative and sound, including music. The remediation of the past in a fictional world or a historiographical text (Chapman’s ‘global context’) can create both resonances and dissonances with the reader’s historical knowledge and background (the “local context”). While resonances are produced when the global context matches the local one, dissonances rise up as the consequence of the contradiction between both contexts. When the latter happens in a videogame without the player purposely and actively seeking the dissonance, they can explore the dissonant, fictional world through an act of passive counter-history (Chapman, 2013: 32-37; Chapman, 2016: 42-46). While these dissonances allegedly defy authenticity, they effectively combine with resonant elements to create more complex and interesting fictional worlds based on historical knowledge. I will argue that, despite the initial dissonances associated with “Nazi rock ‘n’ roll”, when contextualized in the wider fictional world of W:TNO, and combined with an imagined target audience, it becomes a tool that enables the game’s historical verisimilitude.

Music and authenticity

Aided with the aforementioned methodological framework, I will explore how music stands as a structural element in the creation of a pseudo-historical world of fiction such as the one presented in W:TNO. What really stands out when listening to songs licensed by the imaginary corporation Neumond Records is not that they try to duplicate some of the most memorable post-war US greatest hits of the 1950s and 1960s, but that their lyrics are in German. Most of them do not make explicit or serious references to Aryan supremacy and militaristic jargon, two of the main features of early Nazi music (Zeman, 1973: 37-61; Bergmeier & Lotz, 1997: 136-177); however, presenting the lyrics in German seemed sufficient to evoke Nazism. The cultural background of the game medium allowed the publisher to take that shortcut. In videogames, German language is often associated with a particular historical event: World War II. Along with Salvati and Bullinger’s BrandWW2, author Eva Kingsepp argues that games usually focus on transmitting a Nazi atmosphere to feel authentic rather than trying to mediate the past accurately. This sense of “Naziness” is often achieved by introducing certain elements popular culture has associated with the Third Reich: symbols such as swastikas and iron crosses, certain types of paintings, locations such as European villages and Medieval castles, and even artifacts often associated with occultism due to the interest certain Nazi officials showed to the supernatural (Kingsepp, 2002, 2012). Language and sound are also powerful elements of selective authenticity in this kind of games. The soundscapes of World War II-based games not only transmit a sense of immediacy through the shouting of orders and the sound of gunfire and explosions, but they also carry particular meanings: one of them is that the German language is always the voice of the foe. Due to the overrepresentation of Wehrmacht (“Defense Force”) soldiers as opponents, a short word or sentence shouted out in German indicates to the average player that the enemy is nearby and needs to be found and shot down (Kingsepp, 2006: 75-77). This way, even the most ordinary expression or conversation becomes a morally charged signifier in the context of a war game, turning the whole language (and its culture) as an indicator of evil and animosity (Kingsepp, 2006: 81).

The tendencies mentioned above are not entirely applicable to W:TNO. Surprisingly, the game content features a lot of eugenic terminologies 10, especially when the main antagonists enter the scene. However, despite recently being elevated to the status of cultural products, games have become problematic tools of representation because of their playfulness. This fact has made the representation of controversial themes and issues in the game medium a thorny subject. Linderoth and Chapman have found Goffman’s frame theory very useful to explain the process of adapting sensitive issues to the game form. Through this process, themes are ludically framed, this is, they acquire a playful meaning that works as an additional layer of meaning that adds to the ones already given to that theme by culture and society. The new meaning produced by placing the issue into the ludic frame is often perceived as having trivializing properties, a trait called upkeying. For example, airsoft players know that they are engaging in a trivial activity despite fighting each other with accurate replicas of real weapons, and they are very strict in the rules applied to the game and in the language they use––for example, players are not “killed” but “eliminated”. In the reverse case, games are also seen as downkeying artifacts, this is, the actions seen or performed by the player are translated ultimately to the user’s everyday activities. In this case, a concerned father could ban her daughter from playing videogames after witnessing her overrunning pedestrians in Grand Theft Auto and thus believing she will emulate the game as soon as she gets her driving license. Both processes have restricted the appearance of many controversial issues in games, turning them into “value thermometers” that reveal social and cultural norms and acceptable narratives. Therefore, most games must engage in strict culturally sanctioned rules of representation to be acceptable. Regarding Nazism and World War II, developers tend to be over-cautious to dodge potential criticism and accusations of being anti-democratic, homophobic and racist on the basis of sensitive content (Chapman & Linderoth, 2015: 140-143). Thereby, thorny episodes such as the Holocaust or the dropping of the atomic bombs tend to be excluded from digital environments of play, and Nazi symbols and emblems erased from virtual uniforms in games where users can play as a German combatant. Such extreme selectiveness, which apparently contradicts BrandWW2, allows games to avoid being at the center of controversy and social panics but also selectively cleanses the history of Nazism and World War II in the process, making this narratively and aesthetically more acceptable (Chapman & Linderoth, 2015: 149-153).

W:TNO stands as a noteworthy exception to the tendency to use discursive strategies that avoid the problematization of controversial topics or the lack of representation of these particular issues 11––it even features a concentration camp. In this context though, efforts were made to keep the lyrics of Neumond songs ideologically aseptic. I believe that the cause of this decision lies in the apparent contradiction that results of the downkeying attributes of music, which is itself a medium, mediated in a videogame or associated with it. Music has a long-standing tradition of being the carrier of ideological messages. One of the most obvious examples is the anthem, used to transmit certain dogmas ranging from a nation-state world system to liberal or socialist and fascist ideologies, in a subtle and trivialized way (Billig, 1995: 93-127). This explains the cautious stance Jason Menkes, executive producer of Copilot Music + Sound, adopted when he claimed that:

“…no one wanted to create propaganda or create something that could be used for propaganda. If you translate the lyrics, they’re pretty benign: they’re just love songs, or fun pop songs (…) We hired as many non-Aryans as I could for this project. A lot of our artists were Jewish or black or gay”12.

In order to make the former statement clearer, I will make use of the translated lyrics of “Mond, Mond, Ja, Ja”, a Nazi rock hit by the imaginary band Die Käfer:

| German (original) | English translation |

| Drei, Zwo, Eins, Start

Der Mond schaut uns an und wir zurück. Der Mond ist über uns, wird uns gehören. Gestern die Welt und heute der Himmel, Denn uns gehört er und die Freiheit fliegt.

Mond, Mond, Ja, Ja. Vereint wir sind unter dem großen Forscher. Mond, Mond, Ja, Ja. Heute gehört uns die Galaxie.

Vorwärts Brüder unser Mond ist rot. Wir werden den kleinen Fels erobern. Wir sind die jenen, die den Himmel beherrschen, Denn wir sind die Größten im Universum.

(3x) Mond, Mond, Ja, Ja Vereint wir sind unter dem großen Forscher. Mond, Mond, Ja, Ja Heute gehört uns die Galaxie.

|

Three, two, one, start

The moon looks at us and we look back. The moon is above us, will be ours. Yesterday the world and today the sky, For it belongs to us and the Freedom Flies.

Moon, Moon, Yes, Yes United we are under the great researchers. Moon, Moon, Yes, Yes Today the galaxy belongs to us. Forward brothers, our moon is red. We will conquer the small rock. We are those who have mastered the skies, For we are the greatest in the universe. (3x) Moon, Moon, Yes, Yes United we are under the great researchers. Moon, Moon, Yes, Yes Today the galaxy belongs to us. |

Source: Wolfenstein Wikia: “Neumond Records”: http://wolfenstein.wikia.com/wiki/Neumond_Records (Consulted 16/07/2016).

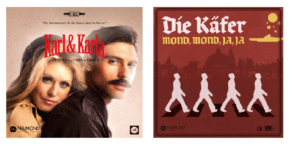

This song tells us about conquest and might – components of the fascist discourse -, but in such an innocuous way that, combined with the catchy pop-rock melody, becomes silly. From the perspective of the selective authenticity framed in a ludic and musical medium, the allusion to the Nazi willingness to expand their Lebensraum is softened by the lack of reference to any nations, territories and ethnicities. Furthermore, the fact that they are singing about the conquest of the Moon, which was far beyond humanity’s reach during the 1930s and 40s, serves as a parody of the Third Reich’s expansionist policies. In addition, the “researchers” mentioned in the chorus refer to Nazi scientists, another cliché of Nazism in pop culture and myth. Finally, the song features in the fictional album ‘Das blaue U-Boot’ (a parody of the ‘Yellow Submarine’), the cover art of which features four silhouettes walking over a pedestrian crossing in a sassy reference to the album cover of The Beatles’ Abbey Road.

Another example worth mentioning is the song ‘Tapferer Kleiner Lieblieng’, from the male-and-female duo ‘Karl und Karla’, apparently specialized in romantic ballads. Here, ‘Karl und Karla’, the German counterparts of Sonny and Cher, sing a cheesy love ballad with silly lyrics that blend corny expressions about love with stereotypes and commonplaces of the German culture and geography. However, the creative process of this particular song is noteworthy. Initially, it was entitled ‘Blue Eyes Forever’, but the supremacist innuendo implied in the sentence finally had it discarded 13. In this context, “Tapferer Kleiner Liebling” (“Brave Little Darling”) seemed a wiser option. Furthermore, the tone in which the German language is used in the medium is also important: in the game’s cut-scenes Nazi language is associated with evil and dehumanized foes, while the ironic and parodic mood of the aforementioned songs would have made its lyrics’ meanings easily misunderstood. Finally, due to the political uses of music, any serious reference to the Third Reich and its dogmas could have been interpreted as an apologetic message.

A myth-history of Nazi and rock ‘n’ roll music:

I next wish to argue that the original score of W:TNO’s is a good example of the tensions between myth and “accurate” historical knowledge in computer games, and also talk about the aesthetic remediation of a particular past by a commercial product in the context of global capitalism. First of all, in order to understand how these particular strategies of song composition work as selective authenticators that link Wolfenstein’s Nazi dystopia with historical commonplaces, it is convenient to explore the history and myths of its two referential themes: The music scene in the Third Reich and the phenomenon of American rock ‘n’ roll in the 1960s. I believe that, in the process, the former is oversimplified while the latter is privileged. This is because post-war American hits became known worldwide and have been elevated to a mythical status, while the musical landscape during the Third Reich had been narrowed to just tools of Nazi propaganda.

I will focus on the former first. Despite attempts by Hitler’s administration, through the Ministry of Propaganda and its different sections, to brainwash the German population with racist and nationalistic ideology, and to influence their cultural tastes (Zeman, 1973: 37-61; Bergmeier and Lotz, 1997: 136-177), the NSDAP changed its approach to music and propaganda as they reached the levers of power. Therefore, the relationship between Nazism and popular music was a thorny one. Germany, especially Berlin, had been the cultural capital of Europe during the 1920s (Bergmeier & Lotz, 1997: 137), which popularized modern music such as jazz and swing popular in Germany. The Partei had a problem with this because Nazis associated these styles with non-“Aryans” who they believed to be Untermenschen. At first, the Regime tried to wipe out danzmusik 14 through a number of bans; however, due to jazz’s popular acclaim, the Nazis tried new strategies such as giving bands a more ‘Aryan’ aesthetic and promoting similar but more ’Aryan’ styles (Pitner, 2014: 149-156). Nevertheless, this mythified understanding of the relationship between Nazism and popular music has been contested recently. Truth is that Hitler’s totalitarian rule did not break with the social uses of music during the Weimar years completely: this is, as a mechanism of distraction and escapism free from propaganda. This is the case of the Schlager or ‘hit song’, an umbrella term initially used to designate commercially successful songs regardless of their style, which could be eclectic but eventually was reduced to sing-along songs. These melodies, whose popularity was usually ephemeral, were used in advertisements and marketing, and their catchy tunes often reached the rest of the world (Currid, 2006: 65-80).

Furthermore, during the Nazi regime, many Germans kept listening to jazz, swing and blues despite the Government’s efforts to eliminate these styles from German popular culture. Many clubs in Berlin and other major cities hosted jazz performances, at the cost of often being often raided by the Gestapo. The allowance of ‘borderline cases’ of jazz music by the authorities didn’t stop the police to strictly (and violently) enforce the law. However, the most audacious and rebel members of the young generations continued to listen to foreign broadcasts that played outlawed music. These youngsters called themselves Hot Boys, Lotter Boys, Jazzkatzen and Swing Boys/Girls/Babies and even had their own bands, such as the Edelweisspiraten and Totenkopfpfadfinder. Unfortunately, many of these rebels were captured by the Gestapo and ended imprisoned in labor camps, some even in Auschwitz (Pitner, 2014: 152-154). After being aware of this obscure chapter in history, we can say that W:TNO’s unintentionally omits the problematic status of popular music in the Third Reich as both a clumsy strategy of domesticity by the authorities and as an active resistance strategy by those opposed to the totalitarian regime. This is because current popular culture tends to associate the sounds of Nazi Germany with certain soundscapes and uses, which resonate with the audiences. Surprisingly, this impression of music in the Third Reich is also framed by American popular music, especially rock ’n’ roll:

“The sound of liberation is the sound of American popular music, a sound that, for these well-trained ears, is absolutely distinct from sounds that might have come before – while the ‘sound’ of the Nazi period serves to metonymize mass evil, the sound of American popular music serves as a stand-in for a culture of thrillingly liberated, but doomed decadence” (Currid, 2006: 2).

Another cause of this apparently strange association is the ubiquity of Nazi imagery, and even ideology, in later manifestations of popular music. Bands and singers whose fame reaches the corners of the world (David Bowie, The Rolling Stones, Chuck Berry, Ramones, etc.) have flirted with National-Socialism, both aesthetically and politically. Furthermore, certain bands have remediated Nazism and its darkest episodes in a satirical tone, while others have tried to empty these symbols of any political meaning (Gonzalo, 2016). These examples illustrate that signifiers of Nazism were appropriated by capitalism, merging with mass media product while reinforcing its mythical status and appeal. Furthermore, the existence of this precedent has the potential to make audiences more receptive to the strategies of authenticity of Newmond Records’ songs and its creators might have thought the same, too. Nazism blends in even further through combination with American popular music of the 1950s and 1960s, yet another mythologized historical phenomenon. Its current status is the outcome of the creation of certain narratives by professional rock critics (who were also witnesses of the historical process) who uncritically associated the “Nazi style” with certain values of youth culture (Walser, 1998: 365). Through this process rock music became an ideological construct, while part of its identity was given by its use as a marketing label (Walser, 1998: 347; Blake, 2004: 490). Additionally, later approaches to the study of the subject have contributed to strengthen the mythical aura of rock and other genres from the era, arguably due to lack of methodological rigor (Santelli, 1999: 238) 15.

By the 1960s involved a radical change in American rock music, which became a channel to denounce social and political issues, thus recovering the tone of protest that characterized many of the 1930s musical compositions. Musicians like Bob Dylan, and Simon and Garfunkel set the precedent of the East Coast protest-based music, while in the West Coast the musical aspect of counterculture adopted a more individualistic tone, with constant references to universal love, personal freedom and the use of drugs as a way of expanding the conscience (Stilwell, 2004: 438-440). This opened the path to the apparition of psychedelic rock and its contestation of traditional moral values and behaviors (Walser, 1998: 361-363), and radical activism against the war and on race, class, gender issues (Stilwell, 2004: 441). Due to its connection to the Civil Rights movement, 1960s rock ‘n’ roll has also been associated in more politicized contexts with civil rights movements like Black Power (Walser, 1998: 360). Although this particular interpretation is not crossed by certain hegemonic strategies, such as the whitewashing processes discussed here, it is still affected by the capitalist process of mythification and appropriation. We can find evidence of this process in how, more than half a century later, these symbols are marketed and thereby de-politicized.

In the arrangement of Neumond Records’ hits, Copilot combined some of the myths mentioned above. Every artist they made up has a clear historical reference, therefore using the hagiographic characteristics of rock to create a pseudo-authentic experience. The musical compositions, based on the most popular songs of these bands, serve as the inter-world identity that connects the fictional particulars with their real but mythified sources. Besides, the use of German lyrics in a playful context establishes a connection between a mythified label of popular music and the traditional enemy of the historical first-person shooter. All these elements resonate with the average videogame player, who is transported to a peculiar dystopia that feels like history.

Music in the game experience

As indicated in the above discussion, Nazi rock ‘n’ roll anchors the fictional world of W:TNO to particular moments in history, acting as a carrier of authenticity. However, the question of how this element fits ludically and narratively in the game stays unresolved. In order to answer this question, we must understand the multiple roles music plays in ludofictional worlds. Music in games is often underestimated by designers and left to the final stages of development (Rogers, 2014: 427; Schell, 2008: 351-352), despite being a crucial component in game design and an integral part of the game experience (Perry & DeMaria, 2009: 502; Cerrati, 2006: 297-303). One of the key roles of music in games is setting a theme, which informs the atmosphere of the virtual experience. An effective soundtrack is one that resonates with the player’s expectations of the game’s theme (Schell, 2008: 48-54). For example, a videogame set in the Wild West would probably have a soundtrack inspired by Ennio Morricone’s arrangements for the movies under the label “spaghetti western” because Sergio Leone’s films have shaped the way the conquest of the West is remembered. Furthermore, using certain instruments, melodies, rhythms, and tones help to evoke specific periods of time and geographical areas (Perry & DeMaria, 2009: 506). However, the effects of resonance are amplified when game music is used diegetically, in other words, when the source of the sound is located within the fictional world. For example, a song emanating from a radio in a room that the player can explore is diegetic. The effectiveness of diegetic sound lies in its ontological status in the fictional world since it is the music its inhabitants listen to (Stevens & Raybould, 2011: 164).

Figures 1, 2: cover art for ‘Tapferer Kleiner Liebling’ and ‘Mond, Mond, Ja, Ja’. Source: Wolfenstein Wikia: “Neumond Records” http://wolfenstein.wikia.com/wiki/Neumond_Records (Consulted 19/07/2016).

In W:TNO, Nazi rock ‘n’ roll is diegetic. It emanates from loudspeakers, radio devices, and stereo sets. For example, at the beginning of Chapter 4 in the game, the player infiltrates the office of a Nazi officer who is listening to Karl und Karla’s ‘Tapferer Kleiner Liebling’ through a gramophone; besides, at the end of Chapter 8, the radio of the vehicle Blazkowicz (the player’s avatar) uses to escape Camp Belica is playing the aforementioned ‘Mond, Mond, Ja, Ja’. As the sound comes from these particular physical sources, the authenticity of the virtual world is enhanced; the 1960s witnessed the commercialization of singles and albums and the proliferation of radio devices that displaced printed music as the main form of distribution (Stilwell, 2004: 423-424, 428). Also, some Neumond LPs are scattered through the game, acting as collectibles that serve as rewards for the players that spent time exploring the game’s locations. Still, players can only obtain three of the songs, and the interaction is limited to listening to them through the journal, a submenu, and by appreciating the art of their covers.

In this sense, the role the songs play in the games’ overall narrative is very restricted, especially when confronted with other games, for example Grand Theft Auto (Rockstar Games, 2001-2016) and Fallout (Bethesda Softworks, 2008-2016). In both, music is used in an ironical way: in the former, as a way to explore the contradictions of contemporary American society and the socially and culturally constructed identities of the different ethnicities that coexist (Miller, 2007, 2008), in the latter, the selected hits from the 1950s, with its lyrics full of glee and joy, make a noteworthy contrast with the post-apocalyptic Wasteland where the action takes place (November, 2014; Cutterham, 2014). Licensed music has been used in videogames since the early 1980s as a marketing strategy and a form of revenue for both music and video-ludic industries, a phenomenon that has been improved along with the development of digital technology (Cerrati, 2006: 298-316). Nowadays, licensing music is an appealing choice for game designers, due to the boost of publicity that popular songs allow; it is also a risky choice because the most well-known songs can demand exorbitant prices (Rogers, 2014: 428). However, as Fallout and Grand Theft Auto exemplify, licensed music can also fulfill ludic-narrative roles. One of the most original uses of a licensed soundtrack in a game is BioShock (2k Boston/2k Games/Take-Two Interactive, 2007). There, music used in a diegetic way is played in certain moments of the story, creating a disturbance due to the clear dissonance between the song’s lyrics and composition and the events of the game, thus transmitting a powerful message (Gibbons, 2011).

However, W:TNO fails where the games discussed above succeed. The original score does not reach its full potential due to its under-representation and limited use within the fictional world. Instead, Bethesda Softworks focused on using the soundtrack almost exclusively in the game’s marketing campaign. This strategy has proven not to be very effective, as the figures of visits to Neumond’s Youtube and Soundcloud accounts show 16. The songs are also available for purchase at the iTunes store, despite the company’s unwillingness to turn the music into a secondary source of revenue. Instead, Pete Hines (vice-president of public relations and marketing at Bethesda Softworks) explains that they wanted music just to give more depth to W:TNO’s universe 17. Therefore, Hines is in the same line of thought as those game designers like the aforementioned Jessie Schell, who believes music is a key factor in a game world’s credibility and mood.

Reaching beyond Neumond Records, one finds that music, specifically rock, nevertheless plays a minor but relevant role in the game’s narrative. In contrast to the music enjoyed by Nazi characters, W:TNO features a member of the resistance called “J.”. This secondary character, a skinny African-American musician who left his home after the United States surrendered to the Third Reich, personifies the mythical image of the counterculture of the 1960s and, by extension, its soundscapes. “J.” can only be found at the Resistance headquarters, where he is always performing majestic electric guitar solos. In the beginning, his presence seems to be only decorative, but at a certain point in the game a cinematic between Blazkowicz and “J.” can be triggered. The protagonist touching without permission the guitarist’s precious instrument starts an argument in which “J.” criticizes the former US Government and, by extension, Blazkowicz’s ideals. He verbally attacks the segregation African-Americans suffered in their very homeland, a politics of discrimination that never ended – we have to bear in mind that, in the dystopian universe of W:TNO, the Civil Rights Movement never took place -. In one of the sharpest critics of the United States’ racial segregation history ever seen in a (pseudo)historical videogame, “J.” bluntly states the following:

“I was little, and my mother wanted to take me to the picture show, but we had to go through the fucking colored entrance. I wanted a hot dog and a lemonade, but the sign says: ‘We don’t serve negroes in this establishment’. You’re a patriot? Blue-eyed jarhead motherfucking Nazi-killing patriot that you are, you’re still a fucking puppet to the man. You’re exactly the kind of guy they ordered in come lynching time. You don’t get it, do you? Before all this, before the Germans, before the war. Back home, man, you were the Nazis” (MachineGames/Bethesda Softworks, 2014).

This is a very controversial subject to address in a game, especially one in which Good and Evil are so clearly defined. It proves that W:TNO’s writers were brave enough to tackle some of the thorniest issues regarding racial politics in the first half of the 20th century to the point of even comparing the US and the Third Reich, two powers that play very rigid roles in the aforementioned popular narratives of World War II. However, “J.” is allowed to express his opinion and avoids controversy because he is authorized by the values he symbolizes. In effect, his race, social background, skills and role allow us to read him as the fictional particular of rock-guitar star Jimmy Hendrix. His inter-world identity is defined by his aesthetics, abilities and the social and cultural tradition he symbolizes. Furthermore, the game highlights this referentiality in “J.”’s last moments. Surrounded by Nazi soldiers, the musician decides that his death will be as loud as possible. Therefore, he plugs his electric guitar into a huge set of amps and starts playing the American national anthem in the same way the historical Hendrix did at Woodstock Festival in 1969. Shortly after that, a group of soldiers storm the room and shoot him dead. The dialog between the German riflemen before opening fire is remarkable:

- What is that?

- Some kind of weapon!

- Shoot him! (MachineGames/Bethesda Softworks, 2014).

Here, music is given tremendous symbolic power, even though the wielder of the melodic weapon ends up dead before his foes. “J.”’s last musical offensive represents the attack of counterculture and its musical manifestations against traditional American values and politics. The Nazi soldiers and the music they consume, Neumond Records’ hits, are the video-ludic counterparts of the situation of popular music in the 1950s: monopolized by a few corporations and censored by the American government, the Anglo-American music industry popularized white male singers and teen idols while hampering the way for black and Latino artists, thus presenting a passive, patriarchal and racist scene with products that were marketed to white audiences (Walser, 1998: 358).

Conclusions

Wolfenstein: The New Order invites the player to explore a world both historical and fantastical. Therefore, in order to become a credible reinterpretation of history that resonates with the user’s historical knowledge, it includes some elements that anchor the fantasy to the historically sanctioned past. Music is one of these elements, but here, it is a replica of the modern music that sprung in the United States at the dawn of the second half of the 20th century. The inter-world identity of this soundtrack was built by mimicking some of the emblematic bands and artists of that era, by selecting their most popular songs, deconstructing them and re-arranging all the elements creating a new musical product that, however, maintains strong similarities with the originals. Once the sound record was composed, it could be used as an element of authenticity that legitimized the historical status of the game’s world, even though as a twisted version of the past. In W:TNO, music has served as an additional element of the process of selective authenticity. As a consequence of the constant re-mediation of certain musical hits, audiences have associated some examples of mainstream music to specific moments of history. This mediated remembrance of the past has shaped the assumed audience’s cultural memory, making them more sensitive to certain messages and signifiers. This has allowed particular narratives to resonate with the audience’s understanding of reality and, by extension, the past (even though not necessarily the most accurately reconstructed past).

In W:TNO, music was made to work as the link between an imagined historical narrative and the ‘real’, sanctioned image of our very past. It has been inserted in a mythical narrative, a narrative that naturalizes a particular interpretation of the past. Musicians like The Beatles, The Animals and The Beach Boys, to mention a few, have become emblematic, acting as symbols of the cultural scene from a glorified era. The idealization of music and the social and cultural movements associated with the era has influenced the way we perceive that fragment of our past to a grade that nowadays it is sometimes difficult to separate reality from its mythical narrative. Another mythified parcel of history is World War II. The grand narratives that explain the conflict, both in academic writing and popular history, usually define the conflict in terms of the fight between Good and Evil. The use of German culture, especially the language, as one of the most easily recognizable features of Nazism in contrast with the heroic Americans who speak English is another manifestation of the the particular perspectives and narratives that have become historically dominant and are privileged in the medium. W:TNO’s German rock ‘n’ roll follows this tradition and perpetuates certain stereotypes and cultural clichés, but it also reinforces the player’s sense of being trapped in a world where Nazis have conquered even popular music. Within an Anglo-American popular gamer mindset, if something sounds like German, it may be labeled as “Nazi”. Moreover, employing a humorous tone has proven to be an effective solution to safeguard the product from the critics.

The question remains if and how this strategy whitewashes the representation of the Third Reich and a more nuanced representation of history. Music in Nazi Germany was not only a tool for propaganda, but also a cultural form that contributed to the distraction and entertainment of its listeners. Understood this way, it is easy to imagine that rock ‘n’ roll would have occurred even if the outcome of World War II had been reversed. However, such an interpretation of a counterfactual course of history is problematic, because it implies the legitimation of a certain historical narrative in which capitalism is naturalized as the historical force that shapes the second half of the 20th century. Besides, even if this metanarrative is contested by the inclusion of an African-American virtuoso of the guitar who fights, in his own style, the yoke of a totalitarian regime and the musical corporations that act as accomplices, the deterministic interpretation of history is still sanctioned. This is because this representation of the past does not get over the myth but, instead, adds another layer to the perception of a past full of ideological traces. That a Jimmy Hendrix-like figure is shown as the embodiment of freedom and progress in a musical language paints history with American hegemonic colors, while also erasing a history of racial inequality. In so doing, it reinforces the myth that the United States and its musicians, black or white, led the way to a cultural, political, social and sexual revolution that confronted a number of traditions and politics that were seen, paraphrasing J., as the Nazis of the era.

The sound record of W:TNO, due to its mythical nature, would have been a very interesting tool to explore a hypothetical Nazi future. Although its narrative use is somehow stereotypical and conservative, it strongly resonates with the local contexts of players. The audience is assumed to recognize the songs as familiar but also to notice their intentionality as a parody. The consequence of this process is a seemingly non-problematic version of rock ‘n’ roll, and a humorous one. Furthermore, the narrative potential was lost somewhere along the development of the game. The decision of using the original score mainly for marketing purposes placed the creative potential inside the boundaries of the sanctioned representations of a consumer society’s demand within a ludic frame––despite its minor role in the game, these songs are still related to a ludic artifact, a game. Neumond Records’ greatest hits could have been more present within the game’s fictional world, while also playing a more subversive part and thus adding another layer of depth. They could have blended with other game elements, such as mechanics, graphics and landscapes, to create a richer narrative, which could have been achieved thanks to the inclusion of J. Developers could have merged the Nazi rock with J’s struggle and thus improve one of the faces of the polyhedral universe of Wolfenstein. Unfortunately, both elements went separate ways, missing the chance of providing a ludic experience similar to BioShock or Fallout. I believe that the tricky inclusion of elements and discourses related to Nazism both in ludic and musical frames played a role in this decision, leaving a very original music recording almost exclusively as a part of a humorous marketing campaign. Nowadays, more game developers are aware of the important role music plays in the creation of a best-selling product. However, the representation of Nazism in games is tricky and still obeys strict implicit policies of representation. Therefore, in Bethesda’s decision on what kind of use to give to Neumond Records, the possibility of target audiences responding negatively to Nazi rock ‘n’ roll may have outweighed the narrative potential derived from giving the songs a more important role in the game world. In the AAA video game industry, miscalculations like the aforesaid trend to be responsible for low sales figures, an outcome that big companies like Bethesda try their best to avoid. To wrap it up, the case of W:TNO stands as emblematic for the affordances, opportunities, and issues arising from the representation of history in games, and it highlights the importance of the sonic dimension to build both historical and mythical worlds.

References

Baron, J. (2010). Digital Historicism: Archival Footage, Digital Interface, and Historiographic Effects in Call of Duty: World at War. Eludamos. Journal for Computer Game Culture, 4 (2), pp. 303-314.

Bergmeier, H. & Lotz, R.E. (1997). Hitler’s Airwaves. The inside story of Nazi radio broadcasting and propaganda swing. London: Yale University Press.

Billig, M. (1995). Banal nationalism. London: Sage.

Blake, A. (2004). To the millenium: Music as twentieth-century commodity. In N. Cook & A. Pople (eds.), The Cambridge History of Twentieth-Century Music, Cambridge (Mass.): Cambridge University Press, pp.478-506.

Cerrati, M. (2006). Video Game Music: Where it Came From, How it is Being Used Today, and Where it is Heading Tomorrow. Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment and Technology Law, 8 (2), pp. 293-334.

Chapman, A. (2013). The Great Game of History – An Analytical Approach to and Analysis of the Videogame as a Historical Form (unpublished doctoral thesis) University of Hull: Hull.

Chapman, A. & Linderoth, J. (2015). Exploring the limits of play. A case study of representations of nazism in games In T. E. Mortensen, J. Linderoth & A. M. L. Brown (eds.), The Dark Side of Game Play: Controversial Issues in Playful Environments, New York: Routledge, pp. 137-153.

Chapman, A. (2016). Digital Games as History. How Videogames Represent the Past and Offer Access to Historical Practice. London: Routledge.

Crabtree, G. (2013). Modding as Digital Reenactment: A Case Study of the Battlefield Series. In A. B. R. Elliott & M. W. Kapell (eds.). Playing with the Past. Digital Games and the Simulation of History. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 199-212.

Currid, B. (2006). A National Acoustics: Music and Mass Publicity in Weimar and Nazi Germany. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Cutterham, T. (2013). Irony and American Historical Consciousness in Fallout 3. In M. W. Kapell & A. B. R. Elliott (eds.). Playing with the Past: Digital Games and the Simulation of History. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 313-326.

Dick, P. K. (1987). The man in the high castle/El hombre en el castillo. Barcelona: Orbis.

Dolezel, L. (1999). Heterocósmica: Ficción y mundos posibles. Madrid: Arco.

Eco, U. (1993): Lector in fabula. Barcelona: Lumen.

Elliott, A. B. R. and Kapell, M. W. (eds.) (2013). Playing with the Past. Digital Games and the Simulation of History. London: Bloomsbury

Fisher, S. (2011). Playing with World War II: A Small-Scale Case Study of Learning in Video Games. Loading… Journal of the Canadian Game Studies Organization, 5 (8), pp. 71-90.

Gibbons, W. (2011). Wrap Your Troubles in Dreams: Popular Music, Narrative, and Dystopia in Bioshock. Game Studies: the international journal of computer game research, 11 (3), retrieved from http://gamestudies.org/1103/articles/gibbons.

Gish, H. (2010). Playing the Second World War: Call of Duty and the Telling of History. Eludamos. Journal for Computer Game Culture, 4 (2), pp. 167-180.

Gonzalo, J. (2015). Mercancía del horror. Fascismo y nazismo en la cultura pop. Libros Crudos.

Kapell, M.W. & Elliott, A.B.R. (2013). Conclusion(s): Playing at True Myths, Engaging with Authentic Histories. In M. W. Kapell & A. B. R. Elliott (eds.). Playing with the Past: Digital Games and the Simulation of History. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 357-369.

Kingsepp, E. (2002). World War II Action Videogames as Post-Modern Fantasy. Third Space Seminar, Transgressing Culture. Malmö and Lund: Stockholm University’s Department of Journalism, Media and Communication, retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/967307/World_War_II_Action_Videogames_as_Post-Modern_Fantasy.

Kingsepp, E. (2006). Immersive Historicity in World War II Digital Games. In HUMAN IT, 8 (2), pp. 60-89.

Kingsepp, E. (2012). The Power of the Black Sun: (oc)cultural perspectives on Nazi/SS esotericism. In 1st International Conference on Contemporary Esotericism. Stockholm: Stockholm University, retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/2156729/_The_Power_of_the_Black_Sun_oc_cultural_perspectives_on_Nazi_SS_esotericism_

Kline, D(2014) (ed.). Digital Gaming Re-imagines the Middle Ages. Abingdon: Routledge

Kotarba, J.A. & Vannini, P. (2009). Understanding Society through Popular Music. London: Routledge.

McCall, J. (2011). Gaming the Past: Using Video Games to Teach Secondary History. Abingdon: Routledge

McNeill, W. (1986). Mythistory, or Truth, Myth, History, and Historians. The American Historical Review, 91 (1), pp. 1-10).

Miller, K. (2007). Jacking the Dial: Radio, Race and Place in ‘Grand Theft Auto’. Ethnomusicology, 51 (3), pp. 402-438.

Miller, K. (2008). Groove Street Grimm: ‘Grand Theft Auto’ and Digital Folklore. The Journal of American Folklore, 1212 (481), pp. 255-285.

Mol, A. A. A. et. al. (2017). The Interactive Past. Archaeology, Heritage and Video Games. Leiden: Sidestone Press

November, J. A. (2013). Fallout and Yesterday’s Impossible Tomorrow. In M. W. Kapell & A. B. R. Elliott (eds.). Playing with the Past: Digital Games and the Simulation of History. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 297-312.

Perry, D. & DeMaria, R. (2009). David Perry on Game Design. A Brainstorming Toolbox. Boston (MA): Cengage Learning (Course Technology).

Planells, A. J. (2015). Videojuegos y mundos de ficción. De Super Mario a Portal. Madrid: Cátedra Signo e Imagen.

Pitner, M. (2014).Popular Music in the Nazi Weltanschauung. International Multilingual Journal of Contemporary Research, 2 (2), pp. 149-156.

Raupach, T. (2014). Towards an Analysis of Strategies of Authenticity Production in World War II First Person Shooter Games. In T. Winnerling & F. Kerschbaumer (eds.). Early Modernity and Video Games. Newcastle upon Thyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 123-138.

Rejack, B. (2007). Toward a Visual Reenactment of History: Video Games and the Recreation of the Past. Rethinking History. The Journal of Theory and Practice, 11 (3), pp. 411-425

Rogers, S. (2014). Level Up! The guide to great video game design. Chichester (West Sussex): Wiley.

Ryan, M-L. (1991). Possible worlds, artificial intelligence and narrative history. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Salvati, A. J. & Bullinger, J. M. (2013). Selective Authenticity and the Playable Past.In M. W. Kapell & A. B. R. Elliott (eds.). Playing with the Past: Digital Games and the Simulation of History. London: Bloomsbury,pp. 153-168.

Santelli, R. (1999). The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum: Myth, Memory, and History. In K. Kelly & E. McDonnell (eds.). Stars don’t stand still in the Sky. Music and Myth. London: Routledge, pp. 236-243.

Schell, J. (2008). The Art of Game Design. A Book of Lenses. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Stevens, R. & Raybould, D. (2011). The Game Audio Tutorial: A Practical Guide to Sound and Music for Interactive Games. Oxford: Focal Press.

Stilwell, R. (2004). Music of the youth revolution: Rock through the 1960s. In N. Cook & A. Pople (eds.). The Cambridge History of Twentieth-Century Music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 418-452.

Tolstoi, L. (2015). Guerra y paz. Barcelona: Penguin Clásicos.

Uricchio, W. (2005). Simulation, history and computer games. In J. Raessens & J. Goldstein (eds.). Handbook of Computer Game Studies. Cambridge (Mass.): The MIT Press

Walser, R. (1998). The rock and roll era. In D. Nicholls (ed.). The Cambridge History of American Music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 345-387.

Winnerling, T. and Kerschbaumer, F. (eds.) (2014). Early Modernity and Video Games. Newcastle upon Thyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing

Zeman, Z.A.B. (1973). Nazi Propaganda. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Web-pages/resources:

Get in the Media: “Brave Little Leiblings: The Alternate Reality of Music in ‘Wolfenstein: The New Order’”, url: http://getinmedia.com/articles/game-careers/brave-little-leiblings-alternate-reality-music-wolfenstein-new-order

The Wall Street Journal: “‘Wolfenstein: The New Order’ Marketing Team Created Fictional Record Label For Promo Campaign”, url: http://blogs.wsj.com/speakeasy/2014/04/04/wolfenstein-the-new-order-marketing-team-created-fictional-record-label-for-promo-campaign/

Wikipedia: “Wolfenstein: The New Order Original Soundtrack”, url: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wolfenstein:_The_New_Order_Original_Game_Soundtrack

Wolfenstein Wikia: “Neumond Records”. url: http://wolfenstein.wikia.com/wiki/Neumond_Records

Ludography

Assassin’s Creed: Unity. Montreal, Canada: Ubisoft Montreal, Ubisoft, 2014.

BioShock. Novato, California (US): 2k Boston, 2k Australia, 2k Games, Feral Interactive, Take-Two Interactive, 2007.

Castle Wolfenstein. Baltimore, US: Muse Software,1981.

Fallout (Franchise). Rockville, Maryland (US): Bethesda Game Studios, Bethesda Softworks, 2008-2016.

Grand Theft Auto (Franchise). Broadway, New York (US): Rockstar Games,Take-Two Interactive, 2001-2016.

Spec-Ops: The Line. Berlin, Germany: Yager Development, 2k Games, 2012.

Turning Point: Fall of Liberty. Southam, Warwickshire (UK): Spark Unlimited, Codemasters, 2008.

Wolfenstein 3D. Rockville, Maryland (US): id Software, Apogee Software, Bethesda Softworks, 1992.

Wolfenstein: The New Order. Rockville, Maryland (US): MachineGames, Bethesda Softworks, 2014.

Wolfenstein: The Old Blood. Rockville, Maryland (US): MachineGames, Bethesda Softworks, 2015.

TV shows:

Spotnitz, F. (creator) (2015): The Man in the High Castle (TV Series). United States: Amazon Studios, Scott Fee Productions, Electric Shepherd Productions, Headline Pictures, Big Light Productions, Picrow, Reunion Pictures.

Discography:

Beatles, The (1966): Yellow Submarine. United Kingdom: Parlophone, Capitol, George Martin.

Beatles, The (1969): Abbey Road. United Kingdom: Apple Records, George Martin.

Beach Boys, The (1965): California Girls. Los Angeles, California: Capitol.

Hooker, John Lee (1962). Boom Boom. United States: Vee-Jay.

Martha and the Vandellas (1965): Nowhere to Run. United States: Gordy, Lamont Dozier, Brian Holland.

Monkees, The (1966): Last Train to Clarksville. Los Angeles, California: Colgems.

Author’s Info:

Fede Peñate Domínguez holds an Undergraduate degree in History from Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria and a Ma. degree in Contemporary History from Universidad Complutense de Madrid, where he is now a PhD student. His research focuses on the remediation of the Spanish Conquest of the Americas in computer games. He is a member of the research project “Collapsed Empires, Post-colonial Nations and the Construction of Historical Consciousness. Infrastructures of Memory after 1917” (HAR2015-64155-P, FEDER). His research is funded by Spain’s Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport (FPU15/00414).

Endnotes:

- From novels to videogames, TV-shows, music, and movies, cultural artifacts often deal with the theme of a Nazi-dominated world. Science fiction author Philip K. Dick (1928-1982) imagined a dystopian United States of America occupied by both the Third Reich and the Greater Japanese Empire; his novel The Man in the High Castle, written in 1962, has inspired a TV series produced by Amazon that aired in 2015. Also, within a film genre dedicated to Nazi-themed fiction, on occasion alternative pasts are explored where the Nazis fulfill their New Order projects. Additionally, some video games address this topic, for example Turning Point: Fall of Liberty (Spark Unlimited/Codemasters, 2008). ▲

- The New Order is one of the latest games in a franchise that was born in 1981 and has become a cornerstone in the first-person shooter genre. Since, W:TNO has been followed by a brief prequel named Wolfenstein: The Old Blood (MachineGames/Bethesda Softworks, 2015) and a sequel, Wolfenstein: The New Colossus (MachineGames/Bethesda Softworks, 2017). ▲

- Some noteworthy works on the issue of World War II in computer games are, for example, Gish (2010), Raupach (2014), Crabtree (2013), Baron (2010), Fisher (2011), and Rejack (2007). ▲

- Wikipedia: “Wolfenstein: The New Order Original Soundtrack” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wolfenstein:_The_New_Order_Original_Game_Soundtrack _blank rel=”noopener noreferrer”>https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wolfenstein:_The_New_Order_Original_Game_Soundtrack (Consulted 16/07/2016). ▲

- For a general overview of the remediation of the past in videogames see, for example, Chapman (2016), Winnerling & Kerschbaumer (2014), Elliott & Kapell (2013), Mol/Ariese-Vandemeulebroucke/Boom/Politopoulos (2017), Uricchio (2005), Kline (2014), and McCall (2011). ▲

- Paul Ricoeur has proposed an interpretative model by which Aristotle’s concept of mimesis – inherited from Plato’s idea of a fraudulent copy of reality, without its derogatory connotation – can be divided in three stages. The process begins with mimesis I or pre-configuration, when the creator fashions the fiction; and it ends with mimesis III or re-configuration when audiences decode the message: positioned between these stages, lies mimesis II or the formal work of fiction (Planells de la Maza, 2015: 36-38, 53-54). ▲

- I believe this is similar to historical discourses, the elaborate work of an author based on the sources and a bibliography. Here, the first phase would consist in the gathering of the historical evidence, its analysis and the revision of literature, and the third being the reception of the work and the debate of the author’s methods, hypothesis, and conclusions ▲

- A critical approach to mythologies was developed by Roland Barthes (1957). Within this semiotic approach, language (understood as any form of representation, such as text, image, sound) is regarded as a system of signs that implicitly connote myth, a veiled ideological discourse that reinforces and naturalizes specific power relations. The historians’ work may therefore be regarded as a narrative practice informed by both fact and myth. This results in a narrative form we could call ‘mythistory’, popular among both historians and game designers. Despite basing their credibility on factual sources, their explanations rest on a particular ideology and the use persuasive strategies to reinforce their claims (see McNeill 1986). ▲

- Following a Barthesian approach, we could say that selective authenticity works on the signifier, providing the representation with an aesthetic that produces an imagined past. ▲

- This is the racial jargon used by Nazism to describe the characteristics and mechanisms that put what they believed was the Aryan “race” above any other. The scene where Blazkowicz meets Frau Irene Engel serves as a good example, since she states that he has “very nice Aryan features” while her subordinate, Bubi, points out that he also fancies Blazkowicz’s blue eyes. ▲

- In World War II ludonarratives, such tendencies often privilege binary interpretations of the conflict and avoid showing its most complex aspects. ▲

- The Wall Street Journal: “‘Wolfenstein: The New Order’ Marketing Team Created Fictional Record Label For Promo Campaign”, http://blogs.wsj.com/speakeasy/2014/04/04/wolfenstein-the-new-order-marketing-team-created-fictional-record-label-for-promo-campaign/ _blank rel=”noopener noreferrer”>http://blogs.wsj.com/speakeasy/2014/04/04/wolfenstein-the-new-order-marketing-team-created-fictional-record-label-for-promo-campaign/ (consulted 18/07/2016). ▲

- Get in the Media – “Brave Little Leiblings: The Alternate Reality of Music in ‘Wolfenstein: The New Order’” http://blogs.wsj.com/speakeasy/2014/04/04/wolfenstein-the-new-order-marketing-team-created-fictional-record-label-for-promo-campaign/ _blank rel=”noopener noreferrer”>http://getinmedia.com/articles/game-careers/brave-little-leiblings-alternate-reality-music-wolfenstein-new-order (Consulted 18/07/2016). ▲

- An umbrella term that Nazis coined to gather jazz, blues and other styles considered inferior and impure. ▲

- Nowadays, rock ‘n’ roll has lost its musical peculiarity and is marketed through a combination of nostalgia and pastiche-like recovery of the past, as the recurrent compilations and re-edition trends show. Indeed, legendary singers and bands are one of the most important foundations of the myth. (Stilwell, 2004: 442). However, legends are usually white and male. The American music industry, especially since the end of the 1950s, systematically whitewashed both its roots and its image through the appropriation of black artists’ works, which were performed by Caucasian musicians. See, for example, Stilwell (2004), Walser (1998), Kotarba & Vannini (2009). ▲

- 35,000 and 25,000 views/plays, respectively. Source: Get in the Media: “Brave Little Leiblings: The Alternate Reality of Music in ‘Wolfenstein: The New Order’” http://getinmedia.com/articles/game-careers/brave-little-leiblings-alternate-reality-music-wolfenstein-new-order _blank rel=”noopener noreferrer”>http://getinmedia.com/articles/game-careers/brave-little-leiblings-alternate-reality-music-wolfenstein-new-order (Consulted 18/07/2016). ▲

- Get in the Media: “Brave Little Leiblings: The Alternate Reality of Music in ‘Wolfenstein: The New Order’” http://getinmedia.com/articles/game-careers/brave-little-leiblings-alternate-reality-music-wolfenstein-new-order _blank rel=”noopener noreferrer”>http://getinmedia.com/articles/game-careers/brave-little-leiblings-alternate-reality-music-wolfenstein-new-order (Consulted 18/07/2016). ▲

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.