Luca Papale (Independent Researcher), Russelline François (Independent Researcher)

A screenshot from Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain (Kojima Productions, 2015).

A screenshot from Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain (Kojima Productions, 2015).

Abstract 1

From its very first entry, the Metal Gear video game series has shown a knack for breaking the fourth wall, sometimes with the intent to shock and surprise the player with gimmicks, at other times to create plot twists aimed to challenge the players’ role in the unfolding of the story. This paper aims to examine how, through the narrative and the gameplay of the final chapter of the canonical Metal Gear series, Hideo Kojima delivers his closing statement on the saga by elevating the empirical player as its ultimate protagonist, while at the same time reaffirming his role as demiurge toying around with the concepts of agency, identity and self.

Keywords: metal gear, avatar, identity, agency, meta-narrative

From villain to hero

In October 2015, Hideo Kojima and Konami severed an employment relationship that dated back to 1986 (Sarkar, 2015). This event marked the end of the Metal Gear saga intended as “A Hideo Kojima Game”, the tagline typically attached to the titles directed by him, although Konami holds the intellectual property and the series continued without its original author.

The last chapter directed and supervised by Kojima is the closure of a circle that had begun almost 30 years before, with the release of the first Metal Gear game (Konami, 1987), in which a rookie Solid Snake infiltrates the fortress of Outer Heaven to dismantle a terrorist threat, only to find out that the terrorist leader is none other than his commander in chief, the legendary soldier known as Big Boss. Said circle was probably not born as such, as the then-young game designer could have not possibly predicted how his experimental game would evolve in a multi-million dollar franchise (Makuch, 2014). Although arguably a step ahead of most video game narratives of the same time, the plot of the first Metal Gear was, in fact, far from complex, with few dialogues and mostly nondescript characters. It can be easily assumed that Kojima had not planned any of the storylines that came after. This is somewhat supported by the fact that, several times across the years, Kojima stated “this is my last Metal Gear”, only to keep on coming back to it (Schreier, 2015).

The series’ span has kept on expanding with each iteration, gradually adding information, branching storylines, new characters, and often negating, correcting, adding or showing under new light events seen in the previously published instalments (Brusseaux, Courcier & El Kanafi, 2015). It is with Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater (Konami Computer Entertainment Japan, 2005) that the series starts to look like the circle we mentioned above, transporting players back in 1964 to have them witness the adventures of a young Big Boss, who is presented as immensely different from the exemplified, cartoon-like villain introduced in the first two games of the saga. Metal Gear Solid: Portable Ops (Kojima Productions, 2006) expands on the past of the series’ original antagonist (now evolved into deuteragonist), and Metal Gear Solid: Peace Walker (Kojima Productions, 2010) definitely elevates Big Boss as the saga’s protagonist, after the departure from the series of Solid Snake in Metal Gear Solid 4: Guns of the Patriots (Kojima Productions, 2008).

Thus, Big Boss is also the protagonist of the two final games of the series, which are Metal Gear Solid V: Ground Zeroes (Kojima Productions, 2014) and Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain (Kojima Productions, 2015). As the number in the titles suggests 2, the two games are actually two halves of one, with the first half being way smaller in scope compared to the latter. The official motivation for splitting the game in two was that Ground Zeroes supposedly served as a demo of sorts to gently introduce players to a completely new set of game mechanics and also to the open-world formula, in contrast to the level design of previous instalments which was much more space-constrained (Serrels, 2013). Of course, there were other, more practical reasons: teasing the audience, encouraging hype and buzz around the product, getting user feedback and data to tweak and improve game mechanics and, last but not least, starting to generate profit by selling something that, in the past, would have been distributed for free.

But other than these superficial, albeit legit reasons, the real significance of splitting Metal Gear Solid V into two separate games was that the two halves, in reality, had two different protagonists.

One in three

Readers who are unfamiliar with the game might be confused by this. We mentioned after all that the protagonist of Metal Gear Solid V is Big Boss, but now we are instead referring to two different characters. The two statements only appear to be a contradiction; in fact, they are both valid and true. Just like Ground Zeroes and The Phantom Pain are, at the same time, two separate games and one single game, the two avatars that players control in these games are, at the same time, two separate persons and both Big Boss.

At the end of Ground Zeros, an explosion destroys the chopper carrying Big Boss, his second-in-command Miller and a few other comrades. The game ends on a cliffhanger, not showing the aftermath of the explosion. The Phantom Pain opens with a first-person perspective that puts the player inside a Cyprus hospital. Nine years have passed since Ground Zeroes: the player’s avatar has been in a coma ever since, after suffering major injuries. He lost most of his left forearm and has shrapnel lodged in his skull that pops out like a horn. He is informed that the shrapnel might interfere with his perception and senses and cause sensorial hallucinations; its removal is impossible due to the high risk of a brain haemorrhage.

In these opening sequences, the doctor who is in charge of taking care of the character asks for his name and date of birth, upon which the player has to manually enter this data. An unassuming player might be slightly confused by the request as they are playing under the assumption of controlling Big Boss, so answering this simple question would already be tricky; however, players might also very easily brush off this dissonance and see it as extra-diegetic, with motivations residing outside the game’s narrative — for instance providing the system with data to be used in online multiplayer leaderboards, matchmaking etc. This sort of “intrusion” of extra-narrative elements into the narrative is not new to video games in general, and especially not to this specific series, which often references hardware and software explicitly during in-game dialogues as noted, among others, by Wolfe (2018) and Fraschini (2003).

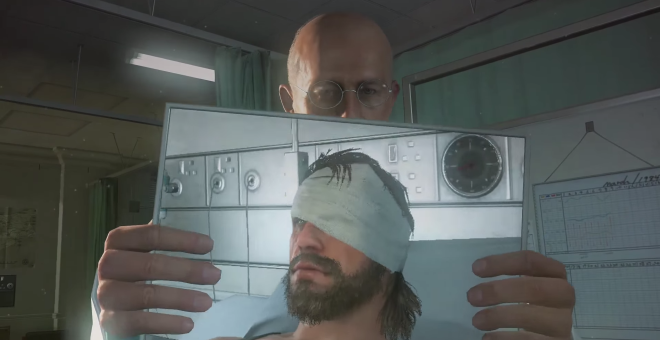

Not long after being asked for their name and date of birth, the players experience another ambiguous event. The same doctor as before informs the avatar that facial plastic surgery will be used to alter his traits and help him go under the radar. Using a mirror, players can finally check his/their appearance, as everything has been shown from a first-person perspective so far: the face in the mirror is unmistakably that of Big Boss, albeit scarred and covered in bandages. Immediately afterwards, players are prompted to use an editor with which they can create their avatar’s custom face 3. However, for a brief moment after completing the personalization of the new appearance, the freshly customized face is shown in the mirror, even if no surgery has taken place yet.

Image 1. The doctor holds a mirror in front of the player’s avatar (Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain).

Image 1. The doctor holds a mirror in front of the player’s avatar (Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain).

The camera cuts to a new scene. The doctor informs the avatar that two days have passed since the surgery and that he is responding well, having almost completely recovered. The doctor proceeds to show him some pictures with Big Boss, Miller and two soldiers posing together and invites him to leave the past behind. Then, once again he places a mirror in front of the avatar, but Big Boss’s facial traits are shown: how does this make sense, if he is supposed to be recovering from the surgery and have a new face? And how come the supposedly new face was shown right before the surgery, instead?

These questions remain unanswered for the time being because this is when the actual game kicks in and players are thrown in the middle of the action, with the hospital being under attack by unknown forces, which leaves the player no time for pondering. Afterwards, the story starts to unfold and the doubts cast by the whole shady facial surgery procedure are easily forgotten, as the event is never mentioned again. From right after the hospital scenario, nothing happens that might cast doubt on the identity of the avatar players control: everything seems to confirm he is Big Boss. However, an attentive player might notice some inconsistencies with the character. For example, Big Boss is never described nor shown in any previously released game of the series as an amputee sporting a bionic arm, a horn-like shrapnel lodged in the skull and a heavily scarred face. Moreover, in this chapter of the series, Big Boss smokes an anachronistic electronic cigar, despite having always been depicted as a tobacco lover with a penchant for Cuban cigars. Finally, one last detail clashes with the character’s personality: in The Phantom Pain, Big Boss isn’t much of a talker, almost presenting himself as “silent protagonist” (Berry, 2015; Mears & Zhu, 2017), which is a typical trait of what can be defined as “shell playable characters” (Lee & Mitchell, 2018) or “mask avatar” (Fraschini, 2003, p. 53) — the kind of digital counterpart that functions best as blank slate onto which players can project their ethics, choices etc. (Papale, 2014). However, all these details can be easily overlooked, deemed as deliberate design choices, or mistaken as the umpteenth case of retroactive continuity.

It’s only at the very end of the game that the ruse is revealed. “The player discovers that everything he or she believes to be true following the initial playthrough of the hospital escape has been a carefully crafted lie, one perpetrated on the characters in-game, but also, as meta-narrative, on the player” (Green, 2017, pp. 105-106). The entire mission set inside the Cyprus hospital is replayed. However, this second time, players are presented with two substantial new details that de facto negate and rewrite what was shown at the beginning of the game, which can thus be interpreted as partial hallucination. It is worth remembering that the protagonist had just awakened from a nine-year coma and had shrapnel in his head that may have messed with his senses; moreover, as we will soon see, his mind had been manipulated.

We see Miller and Big Boss lying down on hospital beds, with a group of doctors working hard to revive the latter. Big Boss appears to be in a coma and a worried Miller is trying to get some understanding of his health state. The camera is shaky and keeps on zooming back and forth on Miller’s and Big Boss’s faces […] Then Miller, breaking the fourth wall, looks into the camera: “What about him?”, he asks. The change is sudden and clear. What initially looked like a medium shot is revealed to be a first-person perspective […] the camera becomes the gaze of a third party viewer (Ferrante, 2016).

Miller’s question is answered by one of the medics: “He… He took some shrapnel — to the head”. And this is the ultimate revelation. The view is in first-person: the medic is talking about the player’s avatar. Big Boss is framed by the camera, so the only possible explanation is that, during the whole game, the player has not been controlling Big Boss.

The screen fades to black, and the sequence already shown at the beginning of The Phantom Pain is replayed. The doctor puts a mirror in front of the avatar, but this time the face reflected in it is the one that, many hours before, players had carefully created with the face editor. “This is you — as you’ve lived until this day”, says the doctor, chasing away any trace of doubt. It is only after the surgery that Big Boss’s face is shown. This time around, there is no incoherent shifting between the two appearances or ambiguity. The avatar is once again given the two pictures already seen at the beginning of the game; however, while the first time they were overlapping and only partially visible, now players can see (no pun intended) the full picture: one of the soldiers standing next to Big Boss and Miller has the same face as the one created with the custom editor.

The two overlapping pictures, once rearranged, show ourselves next to Big Boss, providing the ultimate proof of our physical, ontological presence in the game. The picture and the mirror […] attest the existence of the player inside the game world. The riddle is now solved, as upon flipping the picture we can read an inscription signed by Big Boss dedicated to the player’s name (Ferrante, 2016).

Lastly, one final scene serves as foolproof denouement. The avatar is inside the military base of Diamond Dogs as he pops a cassette tape into a Sony Walkman. The voice is Big Boss’s:

Now do you remember? Who you are? What you were meant to do? I cheated death, thanks to you. And thanks to you I’ve left my mark. You have too — you’ve written your own history. You’re your own man. I’m Big Boss, and you are too… No… He’s the two of us. Together. Where we are today? We built it. This story — this “legend” — it’s ours. We can change the world — and with it, the future. I am you, and you are me. Carry that with you, wherever you go. Thank you… my friend. From here on out, you’re Big Boss.

While these words echo in the room, the player’s avatar observes his reflection in the mirror swinging from Big Boss’s face and his original face. A flashback shows the helicopter exploding at the end of Ground Zeroes, but the scene has an additional, revealing detail: there was a medic on board, a generic character which is never officially introduced by the narrative, basically just one of the many people serving in Big Boss’s army. In the cutscene, the medic protects Big Boss with his own body during the explosion, possibly saving his life.

The epilogue fills the remaining gaps. After the explosion, both Big Boss and the nameless medic fall into a coma. Big Boss awakens before the medic and is briefed about a plan: turning the medic into his doppelgänger by altering his physical appearance through surgery and his mind through hypnotherapy, to convince him to be the one and only Big Boss. The goal of this engineered “phantom” would have been to be a moving target for Big Boss’s enemies; in other words, to take the heat while the real Big Boss was under the radar, plotting his next moves.

This revelation, in a way, retroactively corrects most of the series’ canon. The stories and legends around the messiah-like figure of Big Boss are revealed to be spurred from the actions of not one, but two people4, from a strictly narrative point of view. But we argue that this revelation also has a meta-narrative significance. We interpret this to mean that the empirical player is Big Boss; that every person that has played the Metal Gear saga has contributed to expanding his legend: every in-game action, every small variation of the story, every different point of view all come together to collectively form the mythopoeia of Big Boss.

This fake Big Boss controlled by the player is legitimate. He is the player’s Big Boss, the one they built from their choices on each of the battlefields crossed […] The player, through their actions, manages to turn an unnamed soldier into a Big Boss, perpetuating the myth while the real Big Boss is trying to build his own version of Outer Heaven elsewhere in the world. Perhaps even better, it is possible to interpret that this nameless soldier is none other than the player (Bêty, 2016, p. 81).

Thus, Big Boss is revealed to be triune: at the same time, he is the “real” Big Boss, he is the “phantom” medic, and he is the empirical player.

This narrative twist relocates the player from being a mere spectator to being effectively the co-creator of the story and one of its characters as well; it also marks a sudden shift in the player’s identity and agency, especially in the case in which the player had tried to recreate their appearance when using the face editor at the beginning of the game 5. At the same time, this twist exponentially augments and diminishes the player’s agency: if it is true that the ending elevates the empirical player to being an integral part of Big Boss’s legend, it also displays a loss of agency in the player, who is revealed to having been operating under false premises and been misled by Kojima’s ruse — at least on a first, uninformed playthrough.

Full circle

Let’s go back to the bathroom mirror scene. When the cassette tape stops playing, the avatar flips it and reveals a B side called “Operation Intrude N313”. This is the name of the mission a young Solid Snake carried out in the first Metal Gear. Big Boss’s “phantom” pops the tape in an MSX2 reader (the console for which Metal Gear was originally developed). The contents of the B side aren’t revealed, but we can infer that a time jump of about ten years happens at the moment the cassette is flipped. Metal Gear is set in 1995 while The Phantom Pain is set from 1984 onwards; the B side’s name suggests that this cassette contains the mission briefing for “Operation Intrude N313”, which couldn’t realistically have been planned so long before. Another detail seems to confirm the time jump theory, once again thanks to a revealing mirror: the reflection of the Diamond Dogs logo is replaced by the insignia of Outer Heaven. All of this suggests that this scene is set right before, or during, the events of the first Metal Gear.

Image 2. The “phantom” of Big Boss stares at his reflection. The insignia of Outer Heaven is visible in the back (Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain)

Image 2. The “phantom” of Big Boss stares at his reflection. The insignia of Outer Heaven is visible in the back (Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain)

This brings us to the ultimate revelation. The Big Boss who dies in the explosion of the fortress of Outer Heaven is the “phantom” born from the explosion of the chopper in Ground Zeroes. The “real” Big Boss is elsewhere, building Zanzibar Land (a specular reflection of Outer Heaven). Thus, the Big Boss who is defeated in Metal Gear is, in a way, the empirical player. In a single blow, Kojima rewires and rewrites the player’s role, agency and identity as the saga’s motive force and original villain. Players discover they “killed themselves” years before, by killing Big Boss’s “phantom”.

With regards to Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty (Konami Computer Entertainment Japan, 2002), Fraschini said “Truth is an infinite process. Which means it needs to be constantly rebuilt” (Fraschini, 2003, p. 125). This was the first episode of the saga that strongly presented itself as a meta-narrative, postmodern work (Papale & Fazio, 2018; Markowski, 2015; Higgin 2009). If this proved to be true back then, with Metal Gear Solid V Kojima delivers one final blow onto the player’s identity, revealing how the virtual and physical worlds are intertwined.

Feeling the phantom pain

As previously stated, the path to the publication of Metal Gear Solid V corresponded to the one that saw Kojima and Konami parting ways. The dynamics that led to this breakup are, to this day, quite muddy, but it can be easily inferred that they had a significant impact on the final product, also considering how Kojima Production’s staff ended up, during the last months of development, with restricted access to corporate internet, email and phone calls (Sarkar 2015). This is to some extent confirmed by the fact that a whole storyline (the one related to Eli, a.k.a. the young Liquid Snake, one of the sons of Big Boss) is pretty much rushed to a conclusion that fails to tie several loose ends. As it turns out, this is because a whole mission, the so-called “Mission 51: Kingdom of the Flies”, was originally meant to be included in the final product but never made it in time for the release date, ending up being cut. The existence of this cut content was revealed later on with a collector’s edition of the game that includes artworks, partial cutscenes and recorded dialogues that, when put together and filling in the blanks with some induction, provide a satisfying closure for Eli’s storyline.

The release of this cut material sparked a heated debate on whether the “Mission 51” is to be considered part of the series’ canon. Konami itself weighed on the matter, confirming that it is not canon (Peckham, 2016); but in a time and age where customers’ feedback and user-generated content are paramount in the success of a franchise (Jenkins, 2006, 2013) it is hard to exactly determine who can say what is canon and what is not. In this regard, the players’ agency crosses the boundary of the gameplay and raises interesting questions about authorship and ownership. If the players as collective identity, as we argued before, are the real keystone to the saga, should it be them who determine what is canon, and how? Can and should the game publisher’s stance be taken into account in this evaluation? Or should Kojima’s opinion be the only one that matters, knowing how possessive he has always been in regards to the authorship of his creation (cf. Wolfe, 2018)?

Finally, it might not be too far-fetched to argue that the sense of unfinishedness a player may feel when reaching the conclusion of the game is actually a desired outcome, one that resonates with the theme of the “phantom pain” (the feeling of something that “should” be there, but it is missing) and ultimately the themes of loss and letting go (Dawkins, 2015).

This bait-and-switch technique, after all, is used on two other occasions by Kojima in The Phantom Pain. During the whole game, as players, we are encouraged to build and develop our “Mother Base”, an offshore military facility that we can expand by acquiring materials and skilled personnel. In Mission 43, the Mother Base faces an epidemic that, if spread, would pose a threat to the whole world: a vocal cord parasite that reacts to very specific sound waves that are unique to a given language, and that could potentially be used as an ethnical cleansing tool. During this mission, the player must visit the quarantine zone of the base and put out of their misery all those infected beyond any reasonable doubt. As the mission progresses, it becomes awfully clear that nobody can be spared, because everyone is infected. This moment of the game is the only section of The Phantom Pain where non-lethal options are not possible and the player is forced to kill, effectively destroying their own squad, put together after so much effort and many hours of gameplay; Kojima deprives players of choice after having trained them through narrative, gameplay and scoring system to avoid violence whenever possible (Bêty, 2016).

Following the crisis of Mission 43, Quiet, a mysterious sniper that never speaks, and that is initially a foe before becoming a powerful ally that can be deployed as companion non-playable character (Girina 2018), flees and is captured by enemy soldiers. During the rescue operation, Big Boss is bitten by a venomous snake, and Quiet is forced to use a radio to ask for help. As Quiet is the host of the vocal cord parasite that reacts to the English language, she leaves Big Boss immediately after speaking to avoid spreading the infection and disappears to die alone in the desert. After this sequence, Quiet disappears completely from the game. The player can no longer deploy her in any mission, not even when replaying older ones: “She becomes nothing but a fainting memory that the player can never find again” (Bêty, 2016, p. 87). By depriving the players of Quiet both as a character and as part of the game system, Kojima exponentially expands the sorrow inflicted upon them, after having made sure throughout the whole game that they heavily invested emotionally in Quiet while being under the assumption of having control over the way they interact with her.

In fact, it is technically possible to skip any storyline involving Quiet, as during the first encounter with her the player has the option to kill her. However, chances that the player decides to do this on a first playthrough are slim. Quiet is knocked out; killing her in cold blood would go against the very philosophy of the game itself. Moreover, the player has most likely been exposed to trailers and other promotional material before playing, and these make sure to establish Quiet as a prominent character (Bêty, 2016; Girina 2018): any shrewd player would avoid killing her so early in the game, if not for narrative/emotional motives, at least for fear of missing out on game content. We can thus affirm that players do ultimately have agency over how they perceive the character of Quiet and her subsequent loss; however, both from a narrative and a game design perspective, the invisible hand of Kojima pushes players toward a specific direction, preserving the players’ free will on paper while making sure that the auteur’s vision is fulfilled.

The “impossible” ending

The last commentary Kojima has on players’ agency had long stayed buried deep inside the code of the game before a software bug caused this secret ending to be unlocked prematurely. In fact, in a normal scenario, the unlocking of this scene depends on the collective actions undertaken by players in the online multiplayer section of The Phantom Pain.

In the multiplayer mode, among other things, players can choose whether they want to own nukes or dismantle them; to achieve either goal, they can invade other players’ bases and steal their arsenals. Just like in the real world, owning a nuclear weapon serves as a deterrent but also attracts unwanted attention, so deciding to join or stay out of the nuclear scene is a tactical choice. And just like in the real world, nuclear disarmament seems to remain a utopia.

A cutscene is supposed to be unlocked simultaneously for every player of a given system/console, should the collective nuke count for that environment reach zero. The final quest of The Phantom Pain, in other words, is to convince players all around the world to renounce nuclear power in the interest of a greater good (Gault, 2015; Muncy, 2015). A fitting ending for a series that has always been anti-nuke, and one that also loosely ties The Phantom Pain to the narrative premise of Metal Gear 2: Solid Snake (Konami, 1990), which takes place in a world that has (temporarily) reached full nuclear disarmament. However, it is an ending that still has not been triggered “organically” as hackers and hoarders make it nearly impossible (Alexandra, 2018).

In an ideal world, nobody would have nuclear weapons, as nobody would ultimately benefit from their use; however, it is possibly more dangerous if only one entity holds nuclear power (due to the resulting power imbalance), rather than a multitude; so as long as there is the chance of anyone retaining, acquiring or restoring nuclear armaments, permanent disarmament remains impossible (Schelling 1960). Through gameplay, Kojima effectively illustrates the challenges of nuclear balance and deterrence, and pushes players to reflect on their agency by giving them one last, seemingly impossible mission, one that can only be achieved with a coordinated, continuative and collective effort.

Conclusions

This paper aimed to expose how Kojima comments on players’ agency and toys with their expectations in Metal Gear Solid V through various stratagems: by halving the game into Ground Zeroes and The Phantom Pain, by splitting Big Boss in three, by rewriting the canon to fit the empirical player in the actual narrative. Kojima plays on the phantom pain thematic and uses it as a mechanic by way of giving agency only to take it all away dramatically. True to his nature, Kojima reaffirms his role as auteur by making it clear that he is ultimately in charge; at the same time, though, he recognizes the players’ role in the success of his creation in what is the video game equivalent of a loving farewell letter to his fan base.

References

Alexandra, H. (2018). After years of player warfare, Metal Gear Solid V secret ending triggered prematurely. Kotaku.com. Retrieved from https://kotaku.com/metal-gear-solid-v-s-nuclear-disarmament-ending-was-tri-1822742864.

Bêty, J.M. (2016). Metal Gear Solid V et Hideo Kojima: procédés de transmission et rhétorique auctoriale procédurale (Master’s thesis, Université de Montreal, Montreal, Canada). Retrieved from https://papyrus.bib.umontreal.ca/xmlui/handle/1866/18695.

Berry, R. (2015, September 25). Speak up boss. Middleofnowheregaming.com. Retrieved from https://middleofnowheregaming.com/2015/09/25/speak-up-boss/.

Brusseaux, D., Courcier, N., & El Kanafi, M. (2015). Metal Gear Solid. Une oeuvre culte de Hideo Kojima. Tolouse, France: Third Editions.

Dawkins, D. (2015, September 21). Metal Gear Solid 5 is unfinished? That’s entirely the point. Gamesradar.com. Retrieved from https://www.gamesradar.com/mgs5-unfinished-s-entirely-point/.

Ferrante, M. (2016, January 12). Da Emile Cioran a Friedrich Nietzsche: linguaggio, corpo e relativismo in Metal Gear Solid – The Phantom Pain. Theshelter.online. Retrieved from https://theshelter.online/da-emile-cioran-a-friedrich-nietzsche-linguaggio-corpo-e-relativismo-in-metal-gear-solid-the-2ab500bb438a.

Fraschini, B. (2003). Metal Gear Solid. L’evoluzione del serpente. Milano, Italy: Edizioni Unicopli.

Gault, M. (2015, November 30). ‘Metal Gear Solid V’ just became great anti-nuclear art. Warisboring.com. Retrieved from https://warisboring.com/metal-gear-solid-v-just-became-great-anti-nuclear-art/.

Girina, I. (2018). ‘Needs to be done’: the representation of torture in video games and in Metal Gear Solid V. In B. Jung, & S. Bruzzi (Eds.), Beyond the Rhetoric of Pain. London: Routledge. Retrieved from http://bura.brunel.ac.uk/handle/2438/16598.

Green, A. M. (2017). Posttraumatic stress disorder, trauma, and history in Metal Gear Solid V. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Higgin, T. (2009). “Turn the game console off right now!”: war, subjectivity, and control in Metal Gear Solid 2. In N. B. Huntemann, & M. T. Payne (Eds.), Joystick Soldiers: The Politics of Play in Military Video Games (pp. 252-271). New York: Routledge.

Jenkins, H. (2006). Fans, bloggers and gamers: exploring participatory culture. New York: NYU Press.

Jenkins, H. (2013). Textual poachers: television fans and participatory culture. New York: Routledge.

Lee, T., & Mitchell, A. (2018). Filling in the gaps: “shell” playable characters. In R. Rouse, H. Koenitz, & M. Haahr (Eds.), Interactive storytelling. ICIDS 2018. Lecture notes in computer science (vol. 11318, pp. 240-249). Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

Makuch, E. (2014, February 21). Kojima explains why Metal Gear Solid story is so…complicated. Gamespot.com. Retrieved from https://www.gamespot.com/articles/kojima-explains-why-metal-gear-solid-story-is-so-complicated/1100-6417895/.

Markowski, D. (2015). Postmodernism in video games (Master’s thesis, Technische Universität Braunschweig, Brunswick, Germany). Retrieved from http://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.2849.3209.

Mears, B., & Zhu, J. (2017, August 14-17). Design patterns for silent player characters in narrative-driven games. Proceedings of the International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games – FDG ’17. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1145/3102071.3106366.

Muncy, J. (2015, November 30). Metal Gear Solid V’s final twist? Nuclear disarmament. Wired.com. Retrieved from https://www.wired.com/2015/11/metal-gear-solid-v-nukes/.

Papale, L. (2014). Beyond identification: defining the relationships between player and avatar. Journal Of Games Criticism, 1(2). Retrieved from http://gamescriticism.org/articles/papale-1-2.

Papale, L., & Fazio, L. (2018). Teatro e videogiochi. Dall’avatāra agli avatar. Mercato San Severino, Italy: Edizioni Paguro.

Peckham, M. (2016, August 31). Konami finally answered the ‘Metal Gear Solid 5’ ending question. Time.com. Retrieved from https://time.com/4473908/metal-gear-solid-5-ending/.

Sarkar, S. (2015, December 16). Konami’s bitter, yearlong breakup with Hideo Kojima, explained. Polygon.com. Retrieved from https://www.polygon.com/2015/12/16/10220356/hideo-kojima-konami-explainer-metal-gear-solid-silent-hills.

Schelling, T. C. (1960). The strategy of conflict. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Schreier, J. (2015, March 5). A list of times Hideo Kojima has said he’s done making Metal Gear. Kotaku.com. Retrieved from https://kotaku.com/a-list-of-times-hideo-kojima-has-said-hes-done-making-m-1689707939.

Serrels, M. (2013, November 5). Kojima explains difference between MGSV: The Phantom Pain and MGSV: Ground Zeroes. Kotaku.com.au. Retrieved from https://www.kotaku.com.au/2013/11/kojima-explains-difference-between-mgsv-the-phantom-pain-and-mgsv-ground-zeroes/.

Wolfe, T. (2018). The Kojima code. 1987-2003. Victoria, Canada: Tellwell Talent.

Ludography

Metal Gear, Konami, Japan, 1987.

Metal Gear 2: Solid Snake, Konami, Japan, 1990.

Metal Gear Solid: Peace Walker, Kojima Productions, Japan, 2010.

Metal Gear Solid: Portable Ops, Kojima Productions, Japan, 2006.

Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty, Konami Computer Entertainment Japan, Japan, 2002.

Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater, Konami Computer Entertainment Japan, 2004, Japan.

Metal Gear Solid 4: Guns of the Patriots, Kojima Productions, Japan, 2008.

Metal Gear Solid V: Ground Zeroes, Kojima Productions, Japan, 2014.

Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain, Kojima Productions, Japan, 2015.

Snake’s Revenge, Konami, Japan, 1990.

Authors’ bios

Luca Papale

Independent Researcher

lucapapale88@gmail.com

Russelline François

Independent Researcher

russe.francois@gmail.com

Endnotes

- Parts of this paper are an updated and translated reworking of excerpts from a previous publication co-authored by the first author (Papale & Fazio, 2018). ▲

- This is the first time in the series that the title switches from Arabic numerals to Roman numerals. This is not coincidental: V is the initial of Venom Snake and Vic Boss, two of Big Boss’s many aliases; V also stands for both the victory and the peace sign; finally, the letter V is made of two perfectly symmetrical halves, symbolizing duality. ▲

- This is diegetically interpretable as the character picking his new appearance before the surgery; and once again, the unsuspecting player might just assume that this is all going to be somewhat linked to online multiplayer components of the game. ▲

- This also gives a new meaning to a dialogue included in Metal Gear 2: Solid Snake, where the supporting character Kesler, when called during the fight against Big Boss, states: <Three years ago, when Outer Heaven fell, Big Boss was seriously wounded. He almost died… He lost both hands, both feet, his right eye, and his right ear. But somehow… he survived …I don’t know the details, but apparently it involved turning him into a cyborg. Now he’s half man and half machine.> This dialogue was originally meant to be a tongue-in-cheek reference to the apocryphal Snake’s Revenge (Konami, 1990) in which Big Boss has actually been turned into a cyborg. However, with the new information given by The Phantom Pain, one could reinterpret this dialogue as a sign of the total success of Big Boss’s master scheme: Kesler is a military advisor, but despite that, he is heavily misinformed about him. ▲

- If we consider that the best-case scenario to surprise players is the one in which they tried to recreate their own face with the avatar editor, we can assume that players who don’t identify as male are at a clear disadvantage here, due to the impossibility of selecting a female or non-binary face. ▲

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.