Hanna Wirman (ITU Copenhagen), Rhys Jones (The Hong Kong Polytechnic University)

Abstract

This article discusses researchers’ personal safety by examining a case of studying game arcades in Hong Kong. We approach personal safety from three perspectives as we focus on 1) safety risks associated with specific spaces, 2) risks in meeting and being acquainted with specific people, and 3) risks that are brought along by the theme of a research that may be sensitive. While interview data suggests arcade-goers’ worries over ‘triad’ stereotypes exaggerated by popular culture, police reports and news articles helped us to understand the true and worrying linkages between game arcades and organised crime in Hong Kong even though criminality can by no means be generalised to encompass all arcades.

Introduction

“We can never anticipate the unseen good or evil that may come upon us suddenly out of space.” (H.G. Wells as quoted in Space Invaders)

Games research is typically a low-risk occupation. However, there are topics and areas of study that force a researcher to exercise great care or to encounter situations that are threatening, disturbing, or unsettling. Delving too deep into the Gamergate 1 controversy or putting together a counter-hegemonic games exhibition in a totalitarian state are some examples that may be considered to involve heightened risk. And then there’s organized crime.

This article is an attempt to address the dangers of researching the ‘dark’, illegal aspects of gaming, and their perceived, if not exclusively factual, links to organized crime. It focuses on a taboo of openly discussing researcher safety concerns, specifically in games research. The intimacy and vulnerability uncovered by such concerns form part of the reason why this may be. Researchers may also worry about being ridiculed over seemingly overweening expectations of one’s importance. Organized crime, meanwhile, can seem like a remote phenomenon too unfamiliar to think alongside one’s modest writings on games.

We start by briefly introducing a study about Hong Kong game arcades, known for their links to organized crime syndicates, that prompted us to examine personal safety in relation to our research practice. Our main interest is in how personal safety and research methodological choices are linked in the study of digital games. Here we rely on earlier research that has approached researcher safety in research areas traditionally dealing with ‘risky’ topics, such as criminology or research into so-called difficult populations (e.g. people with substance addiction). The article approaches how association with organized crime turns the ‘field’ of ethnographic research dangerous and unpredictable (Hobbs and Antonopaulos 2014). Alongside introducing challenges that concern research conduct when gathering material, we discuss methodological approaches that help overcome such risks.

Addressing Risk

When studying organized crime in relation to gaming, it is valuable to investigate how other fields tackle the topic from a research methodological point of view. According to Lee-Treweek and Linkogle “Social research involves us entering other people’s workplaces, homes and communities and we are often unaware of the threats of the field until we have been there for some time […] Therefore we posit all qualitative research is to some extent potentially dangerous.” (2000, 10). Earlier studies also suggest that, “A number of risks to the researcher have been identified, including physical threat, psychological harm, and accusations of improper behavior (Social Research Association 2005), and understandably these risks may present differently for qualitative researchers” (Parker & O’Reilly, 2013).

To minimize such risks, Pollock (2009) advocates covert, invisible, and non-participatory observation as potential approaches when studying adversary practices. Analyzing official data, such as statistical records and government reports, as well as media accounts, meanwhile, can help to distance the researcher from the subjects. But to avoid the stereotypical, canonical approaches provided by media accounts and common beliefs, an option is to provide multiple perspectives on the issue. In our study, we started from interviews but soon extended the scope into materials that were available without directly researching people or going into arcades.

Research into sensitive or potentially dangerous areas are important but can prove a challenge for institutional ethics approval boards. In looking at research into conflict, violence, and terrorism, Sluka (2018) looks at an ethical approval required by university review boards and how researchers can develop risk assessment and management plans to help negotiate them. While not as directly dangerous as a live conflict zone, the use of risk assessment to minimize exposure to harm by a researcher was essential when the issues of criminality arose in the study.

Ethnographic studies of criminal networks and the consequences for researchers have been addressed by Martha Huggins and Marie-Louise Glebeek (2003), among others. They detail issues such as meeting people after office hours in the evenings and mention precautions such as taking self-defense classes, avoiding working alone, and carrying a mobile phone. In our study, game arcades are not only dimly lit and far away from the public eye, but also considered highly intimate among those who frequent them. In a study by Lin and Sun (2011), conducted in Taiwan, some gamers treat arcades as their home, for instance.

This article demonstrates a need to better understand how a research topic that tackles aspects of organized crime affects both research participants and researchers. We operate utilizing the concept of ‘risk’ and identified three domains of existing research into personal safety in research, all relevant to our study:

- place: some research takes place in dangerous environments (e.g. Williams et al., 1992),

- people: some research involves people who pose a safety risk (e.g. Cressey, 1967; Fijnaut, 2016), and

- theme and findings: some research address politically, religiously, economically, or culturally sensitive topics which third parties would not like to see published (e.g. Lee and Renzetti, 1990).

The following sections discuss how the place (i.e. game arcades), people (i.e. members of the triads), and theme of the research yielded perceptions of risk in both participants and in us researchers. In qualitative research, methods gain a lot from the researcher’s standpoint since subjective approaches and analyses are not only accepted but encouraged. While scrutinizing our and research participants’ subjective perceptions of risk in this article, we encourage the reader to approach with reflexivity as it offers a view into one’s own research conduct alongside ours.

Hong Kong Game Arcades and Organised Crime

Hong Kong’s arcade culture was most prevalent in the 1980 and 90s with thousands of arcades estimated to be operating in the region. The number of actively operating centers has, not unlike in other parts of the world, plummeted significantly in recent years. In 2002, there were more than 400 game arcades or ‘amusement game centers’ (遊戲機中心) in Hong Kong while by 2018, the number had dropped to less than two hundred. In their place, esports training centers and arenas attracted both government and private investment. The nearly 50-years long history of local arcade gaming (Ng, 2015), meanwhile, continued to change as centers were primarily populated by older adults instead of youngsters.

To document this shift as well as the past experiences of arcade-goers, we conducted semi-structured interviews in Hong Kong. They took place between 2017 and 2019 and helped us to establish the local ‘collective memory’ (Halbwachs, 1992) of arcade play, spaces, and players (cf. Wirman & Jones, 2018, 2019) with a purpose to record and archive the cultural history of Hong Kong’s arcades. The people interviewed played in arcades in the 1980s and 90s. 15 males and 5 females aged between 22 to late 50s were interviewed about their current ideas, meanings, and values associated with game arcades. About half of the interviews took place online through different means of text chatting tools while the other half was conducted face to face.

One of the most prominent themes in the interviews was the assumed pervasiveness of criminal activities in arcades. These were typically linked to the region’s organized crime syndicates, or ‘triads.’ Historically, starting in Mainland China, criminal organizations set up in Hong Kong in the 19th century where they remain as a hidden yet large part of society to this day (Varese & Wong, 2018). It has long been the opinion of the police force that the general public is aware of triad activity in Hong Kong, with the Commissioner of police for Hong Kong in 1960 stating that “Most people are aware of the existence of such societies, but few appreciate the extent of their activities or their dangerous potential in the event of emergencies, whether such be local or international in origin” (Morgan, Bolton & Hutton, 2000).

The major link between gaming culture and the triad gangs lies in the introduction of game arcades in the late 1970s. In the past, arcades often served as venues for money laundering and as gathering spaces for criminals with most people knowing that “in Hong Kong, many lawful public entertainment establishments, especially cinemas, bars, clubs, karaoke lounges, night clubs, discos, restaurants, billiard saloons, and video game centres, are under triad protection” (Chu, 2000). Increased focus on triads in Hong Kong popular culture in the late 1980s and early 90s reflected an increase of triad involvement in the entertainment industry itself in both illegitimate (protection rackets, harassing film stars, etc.) and legitimate forms (producing, financing and distributing films, etc.) (Teo, 1997). Movie scenes of triad brawls and violence inside game centers were not uncommon at the time (Jing & Lau, 1992, 0:32:20) and seemed to inform the negative impressions of arcades of our interviewees as well.

Studying such a potentially sensitive topic presented several ethics concerns that had to be taken into consideration for the safety of our interviewees and ourselves as researchers. For instance, all interviewees were offered the opportunity to have their contributions anonymized. While this is quite a standard option given to people who participate in a study, the sensitive topic and potential revealing interview findings made the practice crucial for us. Participant informed consent was originally obtained on paper, but the documentation was later destroyed so that no paper trail was left behind. We acknowledge that verbal consent becomes a valuable option when there is a need to minimize risk. Full participant anonymity may prove useful when the participants themselves take a more active role in criminal activity or in tackling it.

When engaged in researching people, various practical measures can be taken when personal data is recorded, and sensitive materials handled. This has been explored in relation to digital humanities using the concept of ethics of care (Suomela, Chee, Berendt & Rockwell, 2019) when it comes to handling “toxic data” and researcher safety for Gamergate related research. In our study, this applied to recognizing the power of researchers and research publishing as something that may put participants into risk. It was also possible to make participants less vulnerable by avoiding mentions of specific neighborhoods, arcades, or notable events.

To complicate the situation, many of the interviewed participants had also disobeyed rules about arcade customer age limits. In Hong Kong, arcades operate under the rules that no one aged less than 16 or wearing a school uniform should enter. During our research it became clear that this was a rule almost no one followed, with interviewees admitting they entered arcades regularly when they were aged less than 16. Stories were fondly told of arcade owners who facilitated underage clients by turning a blind eye or who even offered jackets to wear to cover school uniforms. What this meant is that many of our participants were admitting to breaking the law, and while the likelihood of any negative consequences arising from admitting this now – ten, twenty, or even thirty years later – it is something that had to be handled with care for the sake of high research ethics.

During the interviews, a range of personal accounts addressed criminal activities in relation to personal safety. Triad presence in game centers was discussed similarly to an open secret, with almost all interviewees acknowledging the link between the two. Research participants’ perspectives label the entire physical arcade spaces risky. Yet this view is also related to considering risk in certain people, in the unidentified members of triads, who render spaces risky by occupying them. Participants mentioned, for example, that arcades were ‘full of triads’ or breeding grounds for triad recruitment. Most of them discussed triads from the perspective of parental care and explained the concerns of those who children frequented arcades. However, as we will discuss in more detail later, such notions are supported by factual accounts about game arcades as spots for a range of criminal activities still today.

“I think in the early days arcade games do have a very negative image in the mind of parents, because they always think that there is a bunch of gangsters and mobs, but in actual fact most of the arcades is either run by members of the triad or they’re protected by the triad members, because you cannot stay there in such terms, so this is one thing.” (Man, early 50s)

In the interview material, the dangers of game arcades draw from popular cultural depictions, such as movies and from the themes of the games themselves.

“Especially these either cop or gangster, triad related movies, you’d always see a scene in an arcade, where the bad guys are playing there, and the cops go in and they want information from this guy.” 2 (Man, early 40s)

One participant assumed that her parents gained such a perspective from local TV drama, but expressed a lot of uncertainty around the reasons:

“They allow[ed] us to go and the thing is okay because I went with my brother, they didn’t say no. But if I was a parent I would say no because…you could sense the danger there. Yes…maybe they asked the kids to deliver drugs or whatever. You’ll never know. But I think when I look back, like, when I was teenager, I looked back as I…oh no, this kind of place is really danger[ous]. But I don’t know [how] my parents know.” (Woman, mid 40s)

While links between arcade centers and illicit activities have also been noted in other countries such as the UK (Meades 2018) it is the involvement of organized crime that makes Hong Kong’s situation unique and potentially dangerous one to research. Participant perspectives, however, mix personal experiences of danger and parental control with popular stereotypes some participants openly acknowledging the difficulty to distinguish the two from each other. To understand the context of suggested links to criminality, analysis of a range of official documents was done to understand the position of triads in contemporary Hong Kong society. These included news articles, documents provided online by Hong Kong Police, such as annual operational priorities, special topics and news items, and Hong Kong Government press releases, statistical reports, and game center license data.

On ‘Real’ Risks

The link between arcades and triad activity was acknowledged by most of our interview participants. However, their understanding was that these associations were overblown by the media, in keeping with Chu (2005) who states that “people perceive triads as a menace because they are portrayed as such in sensational media reports and gang movies”. While such media reports may be sensational, they do nevertheless reveal that acts of violence are still carried out by triads in game centers on occasion. Among others, a 15-year-old child was beaten unconscious by suspected triad members with a fire extinguisher in a game arcade and caught on CCTV (Lo, 2020). In 2019, there were 1353 reported cases of triad related crime in Hong Kong (Hong Kong Police Force, 2019). And within a year from starting our research on game arcades in Hong Kong, dozens of them were raided, hundreds of thousands of dollars confiscated, loads of gaming machines seized, and hundreds of criminals arrested in ongoing anti-triad police operations (Lo, 2019). A government press release from June 2020 reports that 527 locations including bars, amusement game centers, a cyber café, and residential units were raided and 380 persons arrested during a tripartite anti-crime joint operation, codenamed “THUNDERBOLT 2020” (GovHK, 2020).

Becoming aware of the actual criminal activities linked to game arcades meant that precautions needed to be taken by us when undergoing fieldwork visits to arcades all over Hong Kong. What our participants had suggested about the shady and suspicious triad activities typically linked with game arcades became a visible reality and a central part of our research. Criminality was foregrounded as one of the key themes of the research.

Without digging into the probabilities or actual occurrences of the risks mentioned, the inseparability of perceived an actual risk leads us to accept the concept of risk as theoretical, “not something capable of precise empirical prediction or confirmation” (Shrader-Frechette, 1990, p. 349). As Shrader-Frechette carefully examines, there exists various reasons for the impossibility of differentiating actual risks from perceptions of risk for perceived and actual risk are inseparable and inform each other. Hence, what is discussed in this article is based on how we as researchers, not unlike our research participants, perceived risk when working on a specific research project that involved visits and research into game arcades in Hong Kong. We have tracked back and analyzed the associated personal knowledge (e.g. prior research, news articles, interviews) that informed our judgement, since “even real risks must be known via categories and perceptions” (Ibid., p. 353). Therefore, our analysis and discussion have come to cover both an autoethnographic viewpoint to the risks we perceived and insights into the broader cultural context that builds the notion of danger around the culture and physical spaces we studied.

Following Shrader-Frechette, the reader should keep in mind that “all risks are defined, filtered, and judged on the basis of some subjective standard, whether it is expected utility theory or benefit-cost analysis, or something else” (1990, p. 353). Importantly, then, the different sources of information and experience that contributed to such perceived risk do not form an exhaustive list of what could lead a person, in general, to perceive risks in relation to Hong Kong game arcades. They are, instead, the sources of information that affected our judgement and our research conduct, things that made us reconsider and revisit our methods and our approaches. The things that contributed to us perceiving risk were further filtered through our inability to communicate in local language (Cantonese), our positions in the city as white European immigrants, and our lack of direct access to interview representatives of the police force, for example. However, as the next section will elaborate, some of the issues with access to information itself added to the mystery and exemplified suppression of speech around the arcades.

Secrecy, Intrusion, and Risk

Beyond interviews, working in and around potentially illicit places resulted in challenges in accessing research data. Among others, it was particularly difficult for us to gain access to an official list of game arcades and their addresses in Hong Kong. By law, all game centers in Hong Kong need an “Amusement Game Centre License” from the Home Affairs Department of Licensing. As a government operated department, the list of all premises that currently hold an Amusement Game Centre License should be made freely available to the public. Yet the home affairs department appeared extremely reluctant to provide this list when requested and demanded the request to be made in person at specific offices and during specific times, refused to provide a digital copy, and charged a fee for the printing paper. With such close association between criminal gangs and game centers, it makes sense that the government would not want to release this information so easily, as it would provide a map of triad associated premises within Hong Kong. 3 However, without proof of this being the case, we hereby document such difficulty and can only speculate on the possible reasons.

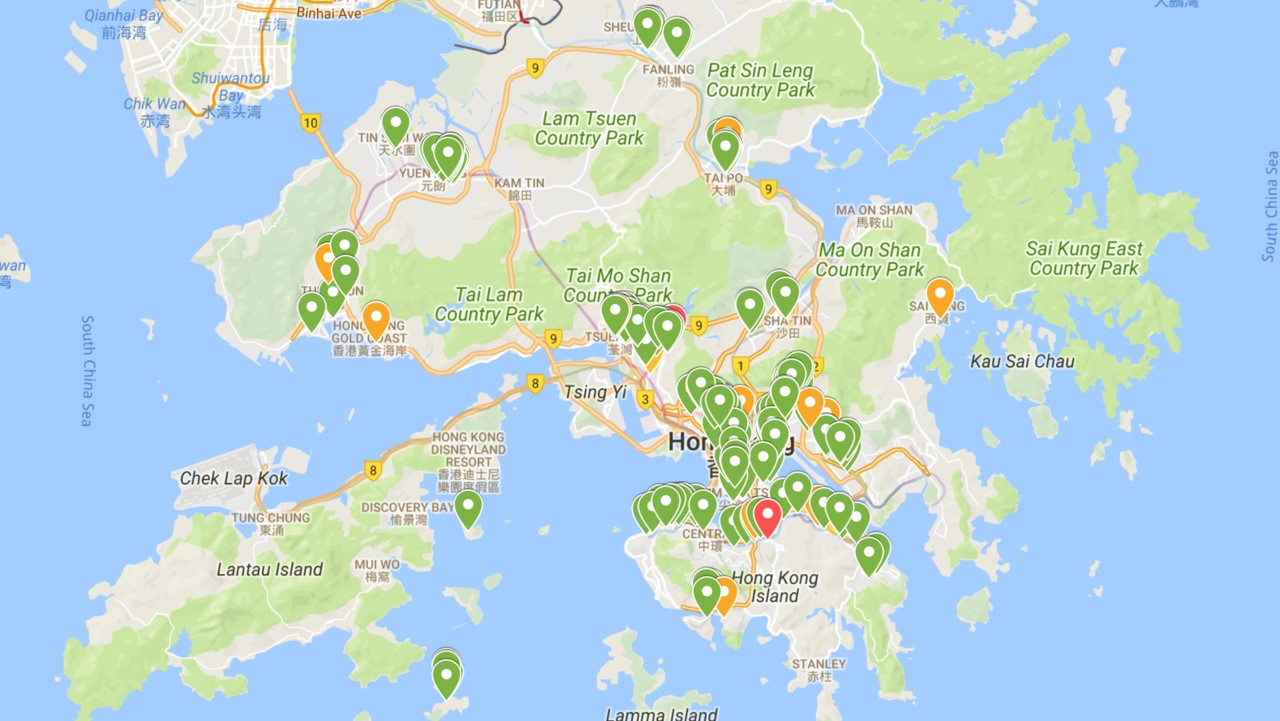

After help from a local contact to navigate the bureaucracy and red tape of the different departments of the Hong Kong Home Affairs Office and Office of Licensing Authority, the arcade address list of 202 addresses was eventually obtained and digitized, creating a custom map of the locations listed. Rhys Jones then walked a total of 94 kilometers over 14 days in May of 2018 to visit the addresses. The result from the location verification was that 4 had become inactive since the government licenses had been issued at the beginning of the year.

While visiting the arcades, risk was always perceived more prevalent in smaller, gambling-focused arcades. The intimacy of such small arcades made it highly obvious when a person entered the space and people inside would be found staring at Rhys presumably trying to figure out why he was there. This was especially evident in the New Territories where foreigners are less likely to live or visit. Tellingly, it was during this research, while walking between arcades, that Rhys was stopped and searched by the police for the first time, which certainly added to the perceived illegitimacy of the task at hand. Doing research in such spaces that may or may not be operated by triads resulted in experiencing risk that was associated with intruding a semi-private territory with a hidden motive.

Photographic documentation, too, was hard to gather as having one’s phone or camera out to try and take pictures was immediately met by a member of staff coming up to Rhys to forbid photography. Deciding whether to go against the staff’s wishes to take photos secretly was considered risky as it could have led to a confrontation and ejection from the premises if spotted. It is understandable that private premises have the power and legal right to protect their patrons by forbidding photography. However, the strict admonishing added to the secrecy and feeling of intrusion in the space which, again, invited thoughts about how feasible, admissible, or even risky it would be to publish research on the topic.

Even when no physical or psychological risk was perceived, Rhys often felt himself unwelcome. With windows covered from outsider gaze, possibility to smoke at premises, commonly worn-out furniture, and dim lighting, the actual physical surroundings added to the illicit ‘feel’ of the arcades. In short, the unkept and dark interiors were in high contrast to the fancy malls and well-lit ‘cha chaan tengs’ and other restaurants in the city. Considering that Hong Kong is one of the safest cities in the world (The Economist Intelligence Unit 2019), the potential risk, even if minuscule, in arcades that stand out from the rest of the city’s fancy modes of entertainment became emphasized.

Another instance of perceived risk inside arcades was triggered by the security measures in place. While the staff taking and exchanging cash were typically older men or women, there was typically a young tattoo-covered man sitting nearby to make sure people did what they were asked to do. It should be noted that in Hong Kong wearing tattoos is not as common as in most European countries or in the US, but still typically associated with criminal and deviant behaviour instead (cf. Ma, 2002, Ho et al., 2006). Even if the tattooed ‘guards’ commonly seen at arcades were not engaged in any sort of deviant behavior, it is fair to assume that their presence was calculated and aimed at intimidation given the prevailing stigma. The perceived risk therefore increased by the co-presence of these assumed triads even if there was no way to verify if they really belonged to the organized crime group or not.4 The mental association of arcades and criminality seemed to fill in the gaps and assumption of triad membership was given to people who “looked” like triads in places that felt increasingly unfamiliar and faraway. To avoid any risk of confrontation, Rhys only took photos of the outer shop fronts to compare with each other instead while writing notes after exiting an arcade to document the interior.

Moreover, issues arose when it came to co-operation with arcade center owners during the project. It was hard to find owners willing to participate or allow access to the game centers after hours to take photos for archiving purposes. The association with criminality, regardless of being an open secret, remained as something that only certain parties had the liberty to talk about

Researcher Standpoint at Risk

Both authors of this study were born and raised in Europe and both are white. Neither of us speaks the local language in Hong Kong, Cantonese. Our positions as white immigrants had implications to research conduct and safety. In terms of language, many slang phrases, or self-references to Hong Kong culture can be obtuse or impenetrable for non-locals to comprehend without additional research into the background and context. Laws concerning the use of certain triad language can constitute a criminal offense in and of itself making translating it a risk for researchers (Bolton & Hutton, 1995). Language barrier can also prove problematic as a non-local researcher, with participants either needing to speak the language of the researcher instead of their native Cantonese or requiring the use of a translator in addition to the non-local researcher. A translator’s presence adds to the vulnerability of the participants and discourages the sharing of sensitive information.

Moreover, non-Chinese researchers stand out from the general customer-base of game arcades. Hong Kong is an ethnically homogenous region with 92% ethically Chinese population as of the 2016 census. Attempting to conduct field work into criminal activity becomes a lot more difficult when the researcher is so obviously present or visible to the participants. It can also lead to unintentional bias of the results, if participants are aware of being observed by a non-local researcher and change their behavior.

While there are drawbacks to being a non-local conducting taboo or sensitive research one cannot ignore certain privileges that are afforded to non-local researchers. On the one hand, our position was close to that described by Huggins and Glebeek as a ‘friendly stranger’ who is “a relatively unthreatening outsider to whom interviewees felt they could disclose their feelings, complaints, and deepest secrets” (2003, p. 374). Accordingly, such outsiders are likely to gather more data and encounter less friction. On the other hand, from a political perspective, non-local researchers enjoy more freedom to research sensitive topics knowing that if any negative consequences ever arose from their research, they may have the option to return to their country of birth while holding that passport. Such opportunities do not exist for local researchers, who if faced with consequences for their research would not be able to go. This is especially relevant regarding studying the criminal aspect of Hong Kong’s arcade scene.

The distinctive political system in Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (S.A.R.) causes its own issues with games research in the region. Special care and attention need to be paid when researching these sensitive political issues, especially relating to mainland China. As an example, during the 2019 demonstrations some of the game arcades operated by mainland Chinese companies were destroyed by demonstrators who suggested they have links to mainland Chinese organized crime (Cheng 2019, Mok & Siu, 2019). When reporting such research results, used language needs to consider the local sensitivities. Unwanted notions of the relationship between Hong Kong and mainland China may be met by objections even in cases where relationships between the two regions are not the focus of the research.

A National Security Law introduced to Hong Kong on the 30th June 2020 has further complicated the execution of research in the region with academics already self-censoring research topics (Normile, 2020) so as not to break the vaguely worded law. Some Hong Kong researchers have voiced concern that applying for international research grants or international collaboration may fall under “foreign collusion” because of the broad scope of this law (Silver, 2020) meaning even non-taboo research topics could become prohibited. It is also questionable how research that uncovers some negative aspects of local culture, conducted by foreigners, could be interpreted.

Conclusions

“Even though all risks are perceived, many of them are also real.” (Shrader-Frechette, 1990, 347)

This article discussed the specific perceived risks associated with different research methods and techniques and the possibilities to alleviate some of the risks in a study into Hong Kong game arcades. Previous research on research safety and risks shows that such concerns can be categorized into personal safety risks related to place, people, and research topic and findings.

In our article we drew a picture of game arcades as potentially risky research environments given their factual links to organized crime in Hong Kong. We observed that arcades as places were often considered risky, but this was because of the assumed people, members of triads, in them and in control of them. These people, moreover, were unknown and hardly identified, yet perceived as a risk to personal safety due to participants’ and researchers’ existing knowledge of factual arcade links to triads and stereotypical portrayals of triad members occupying game arcades in popular culture such as movies. More than people, members of triads refer to the presence of organized crime, a domain quite alien and distant for most research participants and researchers alike. Place and people, then, become merged and blurry, and ‘triad’ a shorthand for a sense of secrecy, thrill, danger, and caution at large.

Referring to government and police reports as well as news articles, we were able to establish a solid link between game arcades and triads in Hong Kong even though this by no means covers all such spaces. Therefore, organized crime, in our short analysis, poses a potential risk to both researchers and research participants. Moreover, the topic of our study itself is potentially politically sensitive and there may be parties whose interests are against publishing details about how game arcades operate in Hong Kong. While such a risk to researcher’s personal safety is extremely vague and nearly impossible to prove, its potential existence should be acknowledged.

With all the limitations, one may be left asking: What is the value of such research that does not even attempt to provide a full account of the various aspects of arcade gaming and leaves out those too risky to approach? Does a researcher need to force themselves to approach dangerous people or go into risky places? Is ‘edgework’ (Lyng, 2005), or voluntary risk-taking for its sensual appeal, a prerequisite for good research in such situations?

Our answer is to support and encourage even the smallest attempts at creating new knowledge while also taking care of oneself and research participants. Beyond physical safety concerns, however, the researcher should also pay attention to how a risky study can drain emotionally: “Research work can be emotionally draining for researchers, and if we are to think about the possibilities of researchers being in risk situations, then we need to consider both physical and emotional risk” (Dickson-Swift et al. 2008, 134). There is, therefore, a further need to study the emotional burden of risky games research.

Finally, Shrader-Frechette reminds us that “risk perceptions often affect risk probabilities, and vice versa” (1990, 350). With appropriate precautions and low risk methods and techniques, it is possible to overcome many of the risks mentioned in this article. One of the goals of this paper was to bring forth and start a conversation about personal safety and risks in games research to allow better preparedness for others.

What comes to the taboo nature of the risks discussed, we see that games researchers who have long justified not only the very existence of their work but also the many positive aspects of their objects of research may find it uncomfortable to address some of the bigger negative sides in the study and play of games. Culturally, the bigger picture behind the interconnectedness of games and organized crime stems from other difficult topics such as gambling in general, illegal gambling in particular, addiction, and money laundering. The lack of research in this area partially results from many games researchers’ lack of knowledge and methodological capability in relation to criminality. Moreover, discussing researcher vulnerabilities is not an easy thing to do especially when they are related to risks that are perceived and difficult to ‘prove’ actual no matter how inseparable the two may be.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dixon Wu, the Founder of RETRO.HK | Hong Kong Game Association (HKGA), for his support to the project.

References

Bolton, K., & Hutton, C. (1995). Bad and Banned Language: Triad Secret Societies, the Censorship of the Cantonese Vernacular, and Colonial Language Policy in Hong Kong. Language in Society, 24(2), 159–186.

Cheng, G. (2019, October 02). Mahjong house by Hokkien clan wasted #antiELAB #ExtraditionLaw #HongKongProtests pic.twitter.com/bilrVcgNZw. Retrieved September 24, 2020, from https://twitter.com/galileocheng/status/1179402567710842881

Chess, S., & Shaw, A. (2015). A conspiracy of fishes, or, how we learned to stop worrying about# GamerGate and embrace hegemonic masculinity. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 59(1), 208-220.

Chu, Y. K. (2000). The Triads as Business. London: Routledge.

Chu, Y.K. Hong Kong Triads after 1997. Trends in Organised Crime 8, 5–12 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12117-005-1033-9

Cressey, D.R. 1967. Methodological Problems in the Study of Organized Crime as a Social Problem. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 374, Combating Crime (Nov., 1967), 101–112.

Dickson-Swift, V., James, E., Kippen, S. & Liamputtong, P. 2008. Risk to researchers in qualitative research on sensitive topics: issues and strategies. Qualitative Health Research, 18(1): 133–44.

Fijnaut, C. 2016. The Containment of Organised Crime and Terrorism. Brill/Nijhoff.

GovHK [The Government of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region]. (2020, June 5). “Tripartite joint operation ‘THUNDERBOLT 2020’ against triads and organised crime.” Press release. Retrieved December 16, 2020, from https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/202006/05/P2020060500321.htm

Halbwachs, M. 1992. On Collective Memory, edited and translated by Lewis A. Coser. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ho, W. S., Ying, S. Y., Chan, P. C., & Chan, H. H. (2006). “Use of onion extract, heparin, allantoin gel in prevention of scarring in Chinese patients having laser removal of tattoos: a prospective randomized controlled trial.” Dermatologic surgery, 32(7), 891-896.

Hobbs, D. and Antonopaulos, A. 2014. How to research organized crime. In The Oxford Handbook of Organized Crime. Oxford University Press, 96-120.

Hong Kong Police Force. (2019). Table 1: Comparison of 2019 and 2018 Crime Situation. In Crime Statistics Comparison. Retrieved from https://www.police.gov.hk/ppp_en/09_statistics/csc_2018_2019.html

Huggins, M. K., & Glebbeek, M. (2003). Women Studying Violent Male Institutions:. Theoretical Criminology, 7(3), 363–387.

Jing, W (Producer), & Lau, A. (Director). (1992). To Live and Die in Tsimshatsui [Motion Picture]. Hong Kong: Upland Films Corporate

The Economist Intelligence Unit. (2019). Safe Cities Index 2019: Urban Safety and Resilience in an interconnected World. Retrieved January 17, 2021, from https://safecities.economist.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Aug-5-ENG-NEC-Safe-Cities-2019-270×210-19-screen.pdf

Lee, R.M. and Renzetti, C.M. 1990. The Problems of Researching Sensitive Topics: An Overview and Introduction. American Behavioral Scientist, 33(5), 510–528.

Lee-Treweek, G and Linkogle, S. 2000. “Putting danger in the frame”. In Danger in the field: risk and ethics in social research, Edited by: Lee-Treweek, G and Linkogle, S. 8–25. London: Routledge.

Lin, H., & Sun, C. (2011). The Role of Onlookers in Arcade Gaming: Frame Analysis of Public Behaviours. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 17(2), 125–137

Lo, C. (2019, January 22). 114 people arrested in building raid on illegal mahjong parlours. Retrieved September 24, 2020, from https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/politics/article/2183194/114-people-aged-41-91-arrested-police-raid-hong-kong

Lo, C. (2020, May 28). Boy, 15, beaten unconscious with fire extinguisher by suspected triads. Retrieved September 23, 2020, from https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/law-and-crime/article/3086549/hong-kong-schoolboy-beaten-unconscious-fire

Lyng, S. (2005). Edgework: The sociology of risk-taking. New York: Routledge.

Ma, E. (2002). “Emotional energy and sub-cultural politics: Alternative bands in post-1997 Hong Kong.” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, 3(2), 187–200.

Meades, A. (2018). The American Arcade Sanitization Crusade and the Amusement Arcade Action Group. In K. Jørgensen & F. Karlsen (Authors), Transgression in games and play (pp. 237–255). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Mok, D., & Siu, P. (2019, August 26). Hong Kong police officer fired warning shot ‘fearing his life was under threat’. Retrieved September 23, 2020, from https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/politics/article/3024289/hong-kong-police-officer-fired-warning-shot-air-because-he?fbclid=IwAR2GqgPCRSd3QHFVKlzSnOzp4hcjpkFTJka-c_NHujtZtVS2qvYc-RGexII

Morgan, W. P., Bolton, K., & Hutton, C. (2000). Triad societies in Hong Kong. London: Routledge.

Ng, B.W.-M. 2015. “Hong Kong.” In Video Games Around the World edited by M.J.P. Wolf, 207–218. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Normile, D. (2020, July 03). Hong Kong universities rattled by new security law. Retrieved September 23, 2020, from https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/07/hong-kong-universities-rattled-new-security-law

Parker, N. & O’Reilly, M. (2013). “We Are Alone in the House”: A Case Study Addressing Researcher Safety and Risk. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 10(4), 341–354.

Pollock, E. 2008. Researching white supremacists online: methodological concerns of researching hate ‘speech’. Internet Journal of Criminology, https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/b93dd4_3686f65909044639a07b17e644b64f92.pdf

Shrader-Frechette, K.S. 1990. Perceived Risks Versus Actual Risks: Managing Hazards through Negotiation, 1 RISK 341.

Silver, A. (2020, June 12). Hong Kong’s contentious national security law concerns some academics. Retrieved September 25, 2020, from https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-01693-y?fbclid=IwAR2BX6ArDe1G4jsxZSWsIXY4mAhWv2oFkqq4x_XHOQ_71h0OGmdRxn7vexE

Sluka, J. A. (2018). Too dangerous for fieldwork? The challenge of institutional risk-management in primary research on conflict, violence and ‘Terrorism’. Contemporary Social Science, 15(2), 241–257.

Suomela, T., Chee, F., Berendt, B., & Rockwell, G. (2019). Applying an Ethics of Care to Internet Research: Gamergate and Digital Humanities. Digital Studies/le Champ Numérique, 9(1), 4.

Teo, S. (1997). Hong Kong cinema: The extra dimensions. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

To, J (Producer), & To, J. (Director). (2003). PTU [Motion Picture]. Hong Kong: Milkyway Image.

Varese, F., & Wong, R. W. (2018). Resurgent Triads? Democratic mobilization and organized crime in Hong Kong. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 51(1), 23–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004865817698191

Williams, T., Dunlap, E., Johnson, B. D., & Hamid, A. (1992). Personal Safety in Dangerous Places. Journal of contemporary ethnography, 21(3), 343–374.

Williamson, A. E., & Burns, N. (2014). The safety of researchers and participants in primary care qualitative research. The British journal of general practice: the journal of the Royal College of

General Practitioners, 64(621), 198–200.

Wirman, H. & Jones, R. (2018, June 11) “Hong Kong Arcades Past and Present”, Paper presented at the Current Perspectives on Game Design seminar, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

Wirman, H. & Jones, R. (2019). “Collective memory of arcade gaming in Hong Kong.” Gaming in the Chinese Context panel, DiGRA 2019, 9-10 August 2019, Kyoto, Japan.

Filmography

PTU, Johnnie To, Hong Kong, 2003

Authors’ Info:

Hanna Wirman

ITU Copenhagen

wirman@itu.dk

Rhys Jones

The Hong Kong Polytechnic University

rhys-g.jones@connect.polyu.hk

- Gamergate was a targeted harassment movement that started in August of 2014 against videogame developer Zoë Quinn which then spread to harassment of journalists, feminists, and other women within the game industry. “Those in the GamerGate movement allege that there is corruption in video games journalism and that feminists are actively working to undermine the video game industry” (Chess & Shaw, 2015). A conspiracy theory linking the Digital Games Research Association (DiGRA) to this alleged corruption led to additional harassment and threats towards DiGRA members and academics. ▲

- Such a scene can be found in the movie PTU. ▲

- Game arcades in Hong Kong marked on a Google map: href=”https://tinyurl.com/yydu5pxu”>https://tinyurl.com/yydu5pxu. ▲

- Given that author background influences judgement of risk, it is worth noting that Rhys Jones has tattoos himself and has a generally positive view towards tattoos. After living several years in a neighbourhood with one of the highest crime rates in Hong Kong, he considers himself somewhat ‘streetwise’ in recognising people’s criminal occupations. ▲

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.