Abstract

The aim of this paper is to consider the emergence of nostalgia videogames in the context of playable game criticism. Mirroring the development of the nostalgia film in cinema, an increasing number of developers are creating videogames that are evocative of past gaming forms, designs, and styles. The primary focus of this paper is to explore the extent to which these nostalgia videogames could be considered games-on-games: games that offer a critical view on game design and development, framed by the nostalgia and cultural memory of both gamers and game developers. Theories of pastiche and parody as applied to literature, film, and art are used to form a basis for the examination of recent nostalgia videogames, all of which demonstrate a degree of reflection on the videogame medium.

Keywords

Game design, nostalgia, parody, pastiche, retro games

The nostalgia videogame

The focus of this essay is the nostalgia videogame, which I define as any contemporary game that explicitly incorporates past aesthetics, design philosophies, or emulated technical limitations. My specific aim is to address two questions: to what extent can we consider contemporary nostalgia videogames to be a form of pastiche or parody that provides a critical engagement with the past? And subsequently, can we identify these nostalgia videogames as part of the wider discourse on games-on-games?

The maturation of videogames and, by extension, the gaming audience, has logically led to a period of introspective original games that demonstrate a fascination with the history of the medium. While publishers and consumers have long been invested in the repackaging, resale, and collecting of videogames (see for instance Swalwell, 2007), in recent years there has been a distinctive shift toward the development of new games that demonstrate nostalgia for past gaming. Videogames that purposefully signalled retro styles were initially discussed as a potential fad in game development (Ramachandran, 2008). Almost a decade later, the expanded production and consumption of retro-styled games demonstrates the broader social, economic, and cultural value of the nostalgia videogame, and suggests that game developers are increasingly engaging with the design philosophies and aesthetics of past gaming eras to inform contemporary game development projects

We might initially dismiss these nostalgia games as overly sentimental, as an obsession with gaming relics. Many critics have indeed dismissed the potential for nostalgia to offer any form of critical engagement with the past. This is perhaps most obvious in critique of the nostalgia film, famously identified as a depthless product of postmodern cultural production by Jameson (1991, pp. 279-296). It has been argued, however, that the nostalgia film offers new ways of interpreting and understanding social and media history (Sprengler, 2009, pp. 84-90). More broadly, the emotional, intellectual, and critical value of nostalgia has been discussed in relation to cultural and media memory (e.g. Boym 2001; Errl, 2011; Sperb, 2016). One of the key arguments in support of critical nostalgia centres on the idea that nostalgia can reveal as much about the present (and our aspirations for the future) as it can the past (Lowenthal, 1985, p.8). While not as rigorous as historical methods – which ultimately aim for an objective evaluation of the past – nostalgic imitations can be regarded as a form of critical engagement with the past framed by personal and collective memory. This in turn reveals more about our current situation: the contemporary social, economic, and cultural issues that we face, and how this directs us to remember the past in particular ways

With specific regards to nostalgia videogames, Garda (2013) offers one of the most useful discussions of nostalgic tendencies in game design. In her analysis, Garda defines retro game design utilising a continuum of restorative to reflective nostalgia, an approach that is generally appropriate to understanding the relationship between nostalgia, memory, and technology (Van der Heijden, 2015). Restorative nostalgia can be aligned with the re-emergence and deployment of classic games on modern hardware, predominantly through online stores. Of more pressing interest to the current essay, reflective nostalgia can be considered the design of neo-retro games: new games that reflect a revival of past styles or designs (as in retro 8-bit, retro 16-bit etc.) The manner in which games reference the past is raised by Garda, which has implications for the type of consumer nostalgia that may be appealed to. Gaming nostalgia may be personal (in that some players have direct memories of the referenced works), or collective and detached (in that some players will not have direct appreciation of the referenced works, but understand the references).

In this essay, I aim to build on this existing work by proposing that the nostalgia videogame could be considered a form of playable game criticism. I explore the notion that these nostalgia videogames are in fact games-on-games: games that have been developed by designers who are critically engaged with both the history of their medium and their own emotional and intellectual connection to gaming. In an age in which games can be quickly sourced and downloaded on to consoles, PCs, and mobile devices, it is easier than ever for gamers to connect with gaming history by playing classic games. But is simply playing a classic game a sufficient means of understanding the aspirations and ideals of past designers and gamers? I explore whether contemporary critical imitation (in the form of pastiche and parody) can help us to understand gaming history, and whether the act of playing these nostalgia videogames can offer unique insights into game making and culture.

This essay is structured in two parts. In the first part I develop a foundation for the analysis of nostalgia videogames by linking the literature on pastiche and parody (which typically focuses on literature, film, and art) to game design. The intention here is to identify useful definitions of pastiche and parody, and in turn consider how these definitions could inform research that is specifically grounded within game design. In the second part of the essay, I select and discuss a series of nostalgia videogames that make reference to period game design and culture.

Critical imitation

Todorov (1984) states that, “intentionally or not, all discourse is in dialogue with prior discourses on the same subject” (p. x ). Expanding on this statement, Todorov suggests that this applies not only to literature, but also to all cultural works, which draw upon the repository of knowledge retained within the collective memory. When it comes to examples of contemporary mimicry – such as the nostalgia videogame – it is therefore pertinent that we question how the imitation relates to the wider discourse on past (and future) game design.

There are many approaches to creating an imitation, as well as a variety of artistic reasons for engaging with mimicry. Hoesterey (2001, pp. 10-15) and Dyer (2007, pp. 11-16) identify a range of imitative modes, including the fake, the homage, and the emulation. Of note here are two particular modes that are well discussed in the literature: the pastiche and the parody. These are closely related imitative modes, so much so that neatly categorising works as belonging to one mode or the other is not necessarily straightforward. Dyer argues that both pastiche and parody are unconcealed imitations (i.e. they do not hide their imitation of an original work, as a forgery does) that signal their source texts. For Dyer, the difference between a pastiche and a parody concerns the evaluative approach: the pastiche invites an open evaluation of its imitation, whereas the parody incorporates a predetermined evaluation of the material being imitated. More generally, the distinction can be summarised as one of similarity and difference: where a pastiche is a work that focuses more on its similarities with an original work (or a series of works, or genre, or the style of an artist), the parody incorporates both similarity and difference to create an ironic effect (Hutcheon, 1985).

If we look first at definitions of pastiche, we can identify that this is an imitative mode that often requires the reader (player) to work to understand and make sense of its references. As Hoesterey (2001) states, “unless one can decipher the intertexts, many postmodern works will offer only a banal aesthetic experience” (p. 27). Hoesterey also stresses the intricacy of a true pastiche. In relation to cinema, she states that contemporary pastiche structuration “goes beyond mere quotation to comprise a complex medley and layering of different styles and motifs” (p. 46). From this perspective, we can suggest two criteria for a videogame pastiche: 1) that a videogame pastiche should incorporate a broad range of gaming references, and 2) that a videogame pastiche should challenge players to exercise their knowledge of gaming history to fully appreciate these references.

Dyer (2007) provides further definitions of pastiche that can aid in the analysis of nostalgia videogames, including the concept that the “pastiche imitates its idea of that which it imitates” (p. 55). In other words, the pastiche offers some insight into how a game designer (or game culture more generally) interprets these original games: it is an imitation that is shaped by contemporary perceptions of the past. Dyer also identifies that the pastiche is constructed via a process of deformation (the selection of traits) and discrepancy (the exaggeration of traits) (pp. 56-58). This process implies a degree of critical engagement on the part of the game designer, and in turn the need for the game player to become a critical player.

In terms of parody, Hutcheon argues that “postmodernist parody is a value-problematizing, de-naturalizing form of acknowledging the history (and through irony, the politics) of representation” (1989, p. 94). Hutcheon regards parody as a legitimate, intellectual, and critical form of engagement with the past: an imitative mode that “signals how present representations come from past ones and what ideological consequences derive from both continuity and difference” (p. 93). Echoing this definition, Harries stresses that:

As a textual system, parody simultaneously says one thing while saying another, always acting as an ironic tease. Thus, it is probably productive to think of parody as a term connoting both closeness and distance as well as the oscillating process that binds both discursive directions. (Harries, 2000, p. 5)

It is this emphasis on establishing ironic difference that we might consider important to analysis of nostalgia videogames. Where game designers have implemented a stark difference with the source of imitation, we could consider what this says about both the original work and our contemporary orientation towards past gaming. For Harries, cinematic parody can be seen to emerge when similarity and difference are contrasted within the film lexicon (the core elements of the film, e.g. the characters, costumes, settings, and props), syntax (the narrative structure), and style (how the film is shot, edited, and presented). Harries also defines six methods for establishing ironic difference that could be useful to our analysis of nostalgia videogames: Reiteration, Inversion, Misdirection, Literalisation, Extraneous Inclusion, and Exaggeration.

While the above definitions allow us to distinguish pastiche and parody, for the purposes of this essay I do not deem it necessary to clearly and definitively separate pastiche from parody, nor to move to classify nostalgia games as falling neatly into one mode or the other. In order to establish a foundation for discussion, I choose to work with the broad definition that these are related modes of unconcealed imitation that are concerned with a variable degree of similarity and difference with original sources, where pastiche tends to emphasise similarity across a range of sources and parody tends to contrast similarity and difference for ironic effect.

What is arguably of most importance to the current discussion is how we relate existing theories of critical imitation to the videogame medium, which comes with its own set of aesthetic and structural qualities. Fundamentally, it is vital that we recognise the distinct properties of the videogame as a structured and symbolic media form. While much has been written about the videogame form, for simplicity I have chosen here to work with the Mäyrä’s core and shell model (Mäyrä, 2008). This model offers an opportunity to translate definitions of pastiche and parody derived from studies of literature, film, and art into the lexicon of videogames. In essence, we could approach analysis of nostalgia videogames by considering how critical imitation has been applied within the videogame shell (the symbolic representation, e.g. the narrative, the audio-visual design) and the videogame core (game rules, systems, and mechanics). For example, we might observe that the ironic difference of parody is established through close similarity within the gameplay design, but inversion and misdirection within the audio-visual representation of settings and characters.

Nostalgia videogames as playable game criticism

In order to address the core research questions of the paper, I have opted to focus on a sample of three videogames that demonstrate different approaches to imitation. These games are Braid (Number None Inc., 2008), Homesickened (Snapman, 2015), and Velocity 2X (Futurlab, 2014). The following analysis draws upon the definitions of pastiche and parody discussed above as a means of interpreting how critical imitation has been deployed. The goal of this analysis is not to try to categorise a nostalgia videogame as definitively parody or pastiche, but to instead discuss how imitation is presented within the game core and shell, and in turn to discuss what this critical imitation can tell us about the place of nostalgia videogames within the wider discourse of games-on-games.

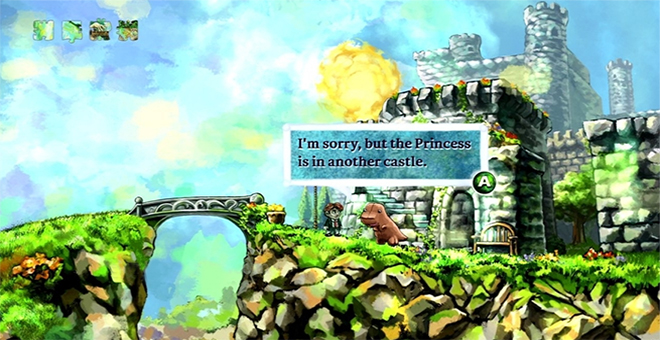

Figure 1: Screenshot from the Xbox 360 version of Braid (2008)

Taking Braid as a first example, we instantly recognise the imitation of Super Mario Bros within both the game shell and core. This includes: adversaries that appear to be piranha plants and goombas, the pursuit of a princess and the message at the end of each level that the “princess is in another castle” (see Figure 1), castles and flags at the end of levels, and even a section of gameplay that imitates the level layout of Donkey Kong. However, we also identify parodic elements within Braid that help to establish critical distance from its source game. Inversion and misdirection, for example, are frequently used to create a clear contrast with Super Mario Bros. The use of parody in Braid allows us to treat it as a game about a game: as a critique not only of Super Mario Bros., but also of our memory of Super Mario Bros. as an icon of the early years of home console gaming.

If we unpack this, we can draw some observations about how Braid operates as a form of playable criticism. Considering firstly the game shell, Braid’s use of transformed visual and narrative elements purposefully draws attention to the childlike innocence of Super Mario Bros. (and the gamer as child), setting up Braid as a kind of re-visitation to childhood (by the gamer as adult). Visually, the impressionistic style of Braid transforms the innocent cartoon world of Super Mario Bros. into a world that appears more refined and mature. Given that Braid was released at a time when the Indie game was moving into the mainstream, we might interpret from this the emerging desire to treat games as an art form, rather than as the consumer electronic toy that they were cast as in the 1980s. In Braid, the pixelated graphics and familiar shapes, forms, and characters of Super Mario Bros. are reimagined in a manner that suggests a distorted memory of the original game: a game from childhood now viewed again through the eyes of adulthood.

Braid’s critical imitation of the narrative of Super Mario Bros. is particularly interesting. On the one hand, Braid utilises a degree of similarity (recognisable characters, the quest to save the princess etc.) On the other hand, Braid uses irony to transform and critique the narrative of Super Mario Bros. This use of misdirection changes not only how we interpret the story and themes of both games, but also how we perceive the player-characters (Mario and Tim) as protagonist-heroes. For instance, one of the most striking examples of irony in Braid is the applied use of misdirection in the game’s final section. At this point, the reversal of time within gameplay reveals that the princess has not been awaiting rescue from Tim, but has actually been trying to escape from the misguided player-character all along. Here we see the protagonist archetype flipped from ideal-hero to anti-hero: Tim is not the knight in shining armour, but a complicated and oftentimes dark individual who appears to be a social outcast. In this critical imitation, Tim is Mario viewed through the eyes of the now cynical adult gamer/game designer, but he could also be interpreted as a reflection of an adult gamer stereotype: that of the loner caught up in a fantasy of heroism, but neglectful of reality.

Within the game core, we can also observe closeness to and distance from Super Mario Bros. The jump mechanic, while important, serves as another form of misdirection. The fundamental mechanic in Braid is actually the ability to reverse time, to both solve problems and undo mistakes. And a consequence of this is a much more difficult and challenging game. Functionally, Braid is a jump-based platformer like Super Mario Bros., but the additional time-reversal mechanic transforms the experience of play. While the gameplay of Super Mario Bros. focuses on skill and timing (attributes that we can associate with the younger gamer), Braid focuses on problem solving and fiendishly perplexing puzzles that seem to purposely facilitate player frustration.

Braid is a nostalgia videogame, but this nostalgia is not merely sentimental. Braid’s nostalgia is necessary to the game’s thematic exploration of time, relationships, loss, and the conflicted nature of game design itself. We could play Braid as a game about games culture (it points to a pivotal point in our collective gaming ‘childhood’, whilst reminding us through both narrative and a time-based mechanic that we can never go back and fully undo the past). We could also play Braid as a game about both game designers and gamers: individuals who have grown up playing games like Super Mario Bros., who had aspirations for the future, but who now have adult lives and adult relationships that may not live up to those past aspirations. Mario always saves the day and wins the adoration of the princess, but Tim is a social outcast whose heroics and adoration exist only in fantasy. From this perspective, the nostalgic imitation of Super Mario Bros. is important to Braid if it is to be understood as a game-on-games. Super Mario Bros. is arguably one of the most widely recognised icons of game design, readily associated with both the emergence of home gaming and the establishment of one of the most important and pervasive game genres: the platformer. Super Mario Bros. can be remembered nostalgically as a game that opened up new future possibilities in gaming. By imitating this game, Braid echoes past aspirations for gaming, while offering new ideas about the current practice and future possibilities of game design.

While Braid’s critical imitation targets the design of a particular game, imitation of historic hardware limitations is one of the common ways in which nostalgia videogames seek to engage with and comment on the past. Of these games, Homesickened (Figure 2) is an excellent example: a nostalgia videogame that strives for an authentic period audiovisual presentation and gameplay design, while simultaneously creating critical distance by problematizing nostalgia itself. By using the aesthetics of period computer hardware to create a strong sense of discomfort, Homesickened turns nostalgia on its head. Homesickness has historically been linked to nostalgia and, at first glance, Homesickened presents an opportunity to return to the warm, familiar landscape of 1980s computing. But the clue is in the title: this is not the remembered cyber space of 80s gaming, but a glaringly unfamiliar and jarring space that is more uncanny than nostalgic.

Figure 2: Screenshot from the Mac OS X version of Homesickened (2015)

The visual design of Homesickened closely imitates the output capabilities of a Color Graphics Adapter (CGA) in 320×200 4-colour mode, where the selected palette comprises black, white, magenta, and cyan. Although other games (such as Downwell or Shovel Knight) imitate the limited colour graphics and low resolutions of early home computers and consoles, few games allow their technological imitation to overwhelm the player experience to the extent that Homesickened does. This is a game that imitates the sluggishness of primitive graphics cards. The slow screen refresh rate as the player moves clumsily through the environment is distinctly uncomfortable for today’s gamers, who are accustomed to precision and accuracy even when retro graphics are deployed. Homesickened makes use of a 3D game engine, allowing for free movement around a 3D world: something that certainly wasn’t possible in the early 1980s. But the use of graphical downgrading results in a drop in response time that seems almost stationary by today’s expectations. On top of this, Homesickened emulates the churning, mechanical sounds of primitive computer hardware, creating an eerie soundtrack. The overall effect is a shattering of nostalgic selectiveness. Homesickened inverts the syntax of techno-nostalgia itself: it draws our attention to the gritty reality of 80s computer hardware, instead of providing a rose-tinted vision of the past that is augmented and improved for contemporary tastes.

In terms of game shell and game core, we can observe how Homesickened specifically targets us – the gamers – and critiques our own tendency to venerate the game technologies of the past. It is a game on games, yes, but more specifically it is a game about gamers and their relationship with their own gaming heritage. As noted above, the thorough downgrading of visual presentation makes it difficult for us to pick out elements in the game world, as they transition between various states of visual clarity as we move towards them. Not only does this serve to accurately emulate the reality of early computer graphics, but it also works as a metaphor for the problem of nostalgia itself, symbolising the fuzzy perception we have of the games we revere. In terms of gameplay design, perhaps one of the most interesting choices is the implementation of unnecessarily awkward controls, imitating the often counterintuitive keyboard controls of 1980s computer games. Most videogames today make use of elaborate control schemes, but these controls tend to feel intuitive to the point that players perform complex actions without paying much attention to the physical pressing of buttons. Navigation and interaction in Homesickened should be intuitive, but interactions (with the space bar) typically require the player to be close to and correctly orientated towards a target (resulting in dissatisfying beeps when the space bar is pressed to no avail), while player navigation is limited to either moving forward/backward or turning on the spot. In terms of both the shell and core, then, Homesickened presents an imitation of the past the critiques not only the historical development of games technology and interfaces, but also (and perhaps more importantly) our rose-tinted orientation towards a gaming past that is more rudimentary and unsatisfying than we often acknowledge.

The referencing to gaming’s past in the above examples is plain to see: Braid makes clear reference to a well-known game franchise, and Homesickened is predicated upon the emulation of period technical limitations. However, we can also identify nostalgia videogames that require players to exercise a deeper knowledge of games history in order to recognise and interpret their multiple layers of references: a quality we can clearly link to the concept of the pastiche.

One particularly good example of a videogame that is perhaps not immediately identifiable as nostalgic is FuturLab’s Velocity 2X (see Figure 3). This is a technically sophisticated game that makes the most of current games technologies: it showcases elegant HD graphics, includes layered techno music and SFX, and provides extremely sensitive and satisfying gameplay, with limited loading times between levels. Even transitions between two very different types of gameplay – space-based shooting and platforming – occur seamlessly. There can be no mistaking, then, that this is an original game franchise made for a contemporary audience. At the same time, however, Velocity 2X is clearly not an original. Both stylistically and mechanically it borrows heavily from past gaming and associated games culture.

Figure 3: Screenshot from the PS4 version of Velocity 2x (2014)

Fundamentally, Velocity 2X is an example of an X meets Y: a product that can be defined by the mashing together of two well-understood concepts. In this case, the X and Y are the vertical-scrolling space shoot-em-up and the sci-fi platformer. These game genres are perhaps best equated to the game series Xenon and Metroid respectively. We can compare Velocity 2X to both of these series and identify significant references. On the one hand, the similarities with Xenon include the upgradeable player-starship, the waves of enemies, and end- and mid-level bosses. On the other hand, the similarities with Metroid include the alien setting, the dichotomy of puzzle and action gameplay, and 2D scrolling levels. Additionally, player-character Kai Tana bears a resemblance to Metroid player-character Samus Aran from later games in the series, particularly the Zero Suit version of Samus from Metroid: Other M. More broadly there are embedded references to games such as WipEout, which clearly influenced not only the speed-orientated gameplay of Velocity 2X but also the mid-90s techno aesthetic.

Velocity 2X is an especially interesting example of a nostalgic videogame pastiche because its final presentation appears strikingly contemporary. The nostalgia of Velocity 2X resides within FuturLab’s reconnection with past game design philosophies and ideals: fast-paced gameplay, incremental introduction of mechanics that gradually build complexity, and an emphasis on many, short levels that increasingly challenge player skill and that encourage replay for higher scores. This kind of broad pastiche of past game design is apparent in other nostalgia videogames that are more evidently retro in their styling: Super Meat Boy, Shovel Knight, or Towerfall Ascension, for example. While parodic nostalgia videogames tend to make more explicit evaluations through the use of similarity and difference, nostalgia videogames such as Velocity 2X are more evaluatively open. It isn’t really important whether or not players understand the references: the game is enjoyable in its own right. But if the player can recognise and understand the references, they will be able to appreciate the game on a deeper level, and even understand the game as a form of playable game criticism. The process of deformation inherent within pastiche – the selection, exaggeration, and concentration of traits from past games – provides us with an insight into what the game designer felt was most valuable about those games.

With a nostalgia videogame such as Velocity 2X, where the critical imitation operates closer to what we may understand as pastiche, we are provided with a game experience that has been carefully (and, most likely, lovingly) curated by a game designer who possesses a deep knowledge of and passion for games. A game such as Velocity 2X borrows particular visual, audio, and ludic references from past games, and then remixes and updates these references for a contemporary audience. It seeks to demonstrate to players what the qualities of these games were (or often, why our collective memories of these games are so resilient). Velocity 2X, then, can be considered a game-on-games that requires players to look back on a range of gaming sources and consider not only what was good about these games in the past, but also how the targeted selection and mixing of these references can make for gaming experiences today that feel simultaneously original yet familiar.

Conclusion

Nostalgia in videogaming can be (and frequently is) dismissed as a sentimental pandering to consumer-creator longing for a lost past. In this context, I believe that it is important that we avoid dismissing a game due to its apparent nostalgic aspirations, and even hold back from using the word nostalgic as a negative term when describing a neo-retro game. It is certainly true that many nostalgia videogames offer only a romanticised view of the past, with limited or no evidence of critical engagement or evaluation. However, this essay has shown that examples of nostalgia videogames, when framed by theories of critical imitation, can be understood as playable explorations of the past. On the one hand, this can include nostalgic pastiches that, through selective referencing and layering, provide us with an insight into the thinking of today’s game designers. In particular, pastiches can help us to understand the game designer’s appreciation of past game design philosophies and play styles. With videogames that incorporate the qualities of the pastiche, players are challenged to become critical players who must work to interpret the references and make an evaluation of the intentions of the designer. On the other hand, videogames that take a more parodic approach can point to the ideas of the past and contrast these with contemporary issues in game design, development, and culture. In these instances, designers are empowered to provide direct commentary on their interpretation of past game design philosophies, styles, and technologies.

Within the wider discourse of games-on-games, I would suggest that the nostalgia videogame offers researchers and designers a means of engaging with the history of the medium. The parallel with the nostalgia film provides us with a start point for both the further study of nostalgia videogames, and the creative exploration of the medium’s past through critical videogame design.

References

Boym, S. (2001). The future of nostalgia. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Braid, Number None, Inc., USA, 2008.

Donkey Kong, Nintendo Research & Development, Nintendo, Japan, 1981.

Downwell, Moppin, Developer Digital, Japan, 2015.

Dyer, R. (2007). Pastiche. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Erll, A. (2011). Memory in culture. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave MacMillan.

Garda, M.B. (2013). Nostalgia in retro game design. Proceedings of DiGRA 2013.

Harries, D. (2000). Film parody. London UK: British Film Institute.

Hoesterey, I. (2001). Pastiche: Cultural memory in art, film, literature. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Homesickened, Snapman, 2015.

Hutcheon, L. (1985). A theory of parody: The teachings of twentieth-century art forms. New York, NY: Methuen.

Hutcheon, L. (1989). The politics of postmodernism. New York, NY: Routledge.

Jameson, F. (1991). Postmodernism or, the cultural logic of late capitalism. London, UK: Verso.

Lowenthal, D. (1985). The past is a foreign country. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Mäyrä, F. (2008). An introduction to game studies. London, UK: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Metroid, Nintendo Research & Development, Nintendo, Japan, 1986.

Metroid: Other M, Team Ninja, Nintendo, Japan, 2010.

Ramachandran, N. (2008, November, 6). Opinion: Neo-retro movement or passing fad? Gamasutra. Retrieved from: http://www.gamasutra.com/view/news/111786/Opinion_NeoRetro__ Movement_Or_Passing_Fad.php.

Shovel Knight, Yacht Club Games, USA, 2013.

Super Meat Boy, Team Meat, USA, 2010.

Sperb, J. (2016). Flickers of film: Nostalgia in the time of digital cinema. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Sprengler, C. (2009). Screening nostalgia: Populuxe props and technicolor aesthetics in contemporary American film. New York, NY: Berghahn Books.

Super Mario Bros., Nintendo, Japan, 1985.

Super Meat Boy, Team Meat, USA, 2010.

Swalwell, M. (2007). The remembering and forgetting of early digital games: From novelty to detritus and back again. Journal of Visual Culture, 6(2), p. 255-273.

Todorov, T. (1984). Mikhail Bakhtin: The dialogical principle. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

Towerfall Ascension, Matt Thorson, Canada, 2014.

WipEout, Psygnosis, Sony Computer Entertainment Europe, Japan, 1995.

Van der Heijden, T. (2015). Technostalgia of the present: From technologies of memory to a memory of technologies. European Journal of Media Studies, Autumn 2015.

Velocity 2x, FuturLab, Sierra Entertainment, UK, 2014.

Xenon, Bitmap Brothers, UK, 1988.

Author contacts

Robin J.S. Sloan – r.sloan@abertay.ac.uk

Photo Credits:

Cover image: Artwork created by the author

Figure 1: Screenshot from the Xbox 360 version of Braid (2008)

Figure 2: Screenshot from the Mac OS X version of Homesickened (2015)

Figure 3: Screenshot from the PS4 version of Velocity 2x (2014)

All sources screen captured from the games as listed in the References.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.