Conor McKeown (King’s College London)

Screenshot of Return to the Obra Dinn (Lucas Pope, 2018)

Screenshot of Return to the Obra Dinn (Lucas Pope, 2018)

Abstract

In this paper, l propose an addition to the existing writing on agency within digital game studies (including but not limited to Murray, 1997; Bogost, 2006; Wardrip-Fruin et al., 2009; Aarseth, 2012), arguing for a recognition of a form of agency in games best understood through the lens of Karen Barad’s writings on agential realism. To highlight how this ‘intra-active’ perspective significantly diverges from and disrupts current concepts of agency, I present a reading of Lucas Pope’s Return of the Obra Dinn (2018), a game that highlights how several key elements of Barad’s novel formulation of agency can greatly benefit the study of digital games. I highlight how, through a balance of design and narrative craft, Obra Dinn eschews the trend for defining agency as relative to the breadth of potential player actions (Murray, 1997) – or else the extent to which a computer can support the illusion of a potential for action (Wardrip-Fruin et al., 2009) – in favour of providing players with something simultaneously more mundane and yet existentially profound. In playing this game, an agential-realist reading suggests, players are caught up in the becoming of many things: the becoming of the game but also of elements of themselves. Indeed, Janik (2017) has concisely outlined the importance of Barad’s work for understanding the production of the player through play. However, in this paper, I seek to further that idea (and several other applications of Barad’s work to the study of games) and contend that an intra-active understanding of play necessitates the understanding of a continued materialisation beyond the player. Embracing an intra-active view of agency when reading Obra Dinn, the seemingly banal task players are set – of completing an insurance claim for the 19th century East India Company – is recast as a meaningful facet of the production of spacetime, humanist narratives and ongoing history. Although this may sound grandiose, an essential element of the impact of Obra Dinn, is the player being cast in the role of an observer, rather than an instigator of action: players are not given the power to shape reality but are instead asked to see themselves and their actions as a powerless but essential part of wider phenomena. Bringing this novel theory of agency to bear on Obra Dinn player actions are refigured as entangled in the production of the meaningful materiality of a heightened fiction on the high-seas and a Lovecraftian unreality. Yet, ultimately, these players/their play is also intricately entangled into the enduring legacy of the racial tensions of British colonialism.

Keywords: agency, agential-realism, Obra Dinn, Lucas Pope, Karen Barad

Introduction

A trend is emerging within game studies. Amidst a backdrop of materialist engagements that seek to decentralise and query the anthropocentric dimensions of the field (Keogh, 2018; Leorke & Wood, 2019), several scholars look to Karen Barad’s agential-realism (Janik, 2017; Wilde & Evans, 2017; Chang, 2017; Stone, 2018; McKeown, 2019) for a theoretical frame to ground their various explorations of the medium. One possible reason for this emerging trend may be the potential for Barad’s work to enable novel concepts of – among other things – interaction and agency. Though I will provide a more detailed explanation of this later in the paper, Barad’s work questions the fundamental metaphysics of much of Western philosophy. In this, it unveils a radical reframing of agency as a co-constitutional force both preceding and productive of (only ever “apparent”) things. This new ontology (or “onto-ethico-epistemology” in Barad’s words) comes with an explicit moral imperative: if all things are understood as entangled, actions become equally entangled. Consequently, this shared agency produces a shared responsibility in the production of an entangled history. In this paper, I will outline a selection of existing writing on agency within digital game studies, highlighting how Barad’s theory of agency diverges from and disrupts current concepts. To make clear exactly how Barad’s work could impact game studies, I provide an agential-realist reading of a game that highlights several elements of this novel concept of agency as I have understood it. I highlight how Lucas Pope’s Return of the Obra Dinn (2018), through a skilful blending of mechanic design and narrative craft, eschews the trend of placing immediate importance on player actions in favour of providing players with an experience that is simultaneously functionally limited yet, when read intra-actively, existentially grand. Through the player’s mundane activity in a fictional, fantastical setting, action comes to produce matter but also meaning in such a way that the seemingly banal central action – completing an insurance claim for the 19th century East India Company – comes to transform time and space. Essential to the impact of Obra Dinn, however, is that the player is not cast as the instigator of these actions, but rather, as an observer.

In this paper, I argue that Obra Dinn presents players with a decentralised or intra-active form of agency that reveals the enduring power of small actions when understood as part of a chain of events extending throughout history and space. Actions, it shows, are not meaningful for their ability to shape reality – as conventional game studies writings on agency would lead us to believe – but meaningful in their ability to play a co-constitutive role in producing reality. The seemingly simple actions players can take are recontextualised as simultaneously produced by and as small parts of an intricate phenomenal assemblage. Pushing our theoretical understanding of agency within game studies to its limits, we can understand this more distributed form of agency (or intra-activity) as entangled in the production of many (apparent) things. Although Janik has argued that intra-active understandings of play can be seen as giving rise to player themselves (Janik, 2017) I argue for that in Obra Dinn we can see the potential for agency in a digital game as a force entangled in the production of multiple other apparent things: firstly, a heightened interpersonal drama on the high-seas; secondly, a Lovecraftian unreality, and ultimately, an intricately interwoven entanglement of physical matter of player actions and computational processing, with the so-called meaning or socio-cultural legacy of the racial tensions of British colonialism.

Defining Agency

Within digital game studies, scholars are fortunate to enjoy a wide range of definitions of agency. So many, in fact, that though I will attempt to discuss a range of these theories within this paper, there are many more that I could not discuss for the sake of brevity. That being said, the discussion around agency in game studies can broadly be traced to Janet Murray’s clear and unambiguous definition of agency as: “the satisfying power to take meaningful action and see the results of our decisions and choices” (2016, p. 126). Murray’s idea of agency should sound familiar to students of either literature studies or much of humanist philosophy, wherein the ability of either a fictional character or a living human to express complex and wilful actions stands as a steadfast defence against, on the one hand, poor, plot-driven writing and a deterministic universe on the other.

Murray discusses a range of examples of what meaningful agency might be, beginning small with the simple task of opening documents on a computer: users trust that their actions will elicit uncomplicated and reliable results. However, it is not long before Murray draws on media such as Greek theatre and cinema, contending that it is a necessity for there to be dramatic stakes within gaming if they are to be seen as a new narrative medium. Dreaming of what potential agency-driven heights (driven by the context of previous narrative forms) might be possible within a digital narrative, contrasting multilinear digital narratives against those with only one outcome, Murray writes, “the desire for agency in digital environments makes us impatient when our options are so limited. We want an open road with wide latitude to explore and more than one way to get somewhere” (p. 126). In this, Murray separates the notions of interactivity and agency. Though we might accept that using a word processor is interactive, we can equally accept Dr Zhivago as a character with agency as he is, relatively speaking, free to act and those actions have obvious consequences. At the same time, Murray breaks agency itself into distinct levels. She writes, “some games, like chess, can have relatively few or infrequent actions but a high degree of agency, since the actions are highly autonomous, selected from a large range of possible choices, and wholly determine the course of the game” (p. 127). Following this logic, agency is something that a game can have in greater or lesser quantities. It is not just the frequency of action, but the autonomy afforded by action, the range of possibilities for acting and the impacts upon the course of the game that actions have that characterise the degree of agency. As such, although opening a document on a computer is an interaction, or possibly even an expression of agency, that agency is limited. A fully realised virtual world in which players could do anything they like would provide much greater agency.

It’s worth noting that Murray does not argue that a fully realised virtual world exists; rather, she imagines, inspired by popular science fiction, a ‘holodeck’ in which a user’s every desire can be realised. This concept of agency as contingent upon what can be supported by the computer system is what I will be arguing against in this paper – instead of holding up agency as a possibility that has not been and may never be realised I believe that we can rather seek to use the concept and its reverberations within digital games to better understand the implications of actions.

Murray’s concept of agency is echoed throughout a host of associated scholarship: Espen Aarseth implies that agency is a quality that correlates in various ways to the construction of the game world, objects in that world, characters and the extent to which events in the game are either scripted or open to change (Aarseth, 2012). Writing specifically on how the objects in a game world imbue players with agency, he writes, “[objects] are important because they determine the degree of player agency in the game: a game which allows great player freedom in creating or modifying objects will at the same time not be able to afford strong narrative control” (p. 8). Aarseth’s formulation of agency is not so different to Murray’s, given its emphasis on player freedom and choice. Though the emphasis for Aarseth is on agency through game design rather than through the satisfaction of player desires or narrative excellence, these points – Murray’s key points for agency – are also factored into his attempt to tabulate the potential for agency, using a taxonomical grid system of agency-fostering elements. For Aarseth, as Murray, a game is a more highly ‘agential’ (that is to say, more imbued with agency) experience, the more the player has the ability to – or, through good design, believes they have the ability to – affect changes within the game world, at the level of play or narrative or both. This notion that agency is ultimately manifest within the ability to instigate change is visible in several other author’s work, such as in Jaime Banks (2015) who suggests that players can find forms of agency in games through the avatars they use, inhabit, create or become. Although the focus is shifted once again, away from narrative or ludic practices and towards character, the emphasis remains on the experience of the player.

In contrast Murray and Aarseth then, Wardrip-Fruin et al (2009) directly question commonplace assumptions of agency, contending that “agency is not simply ‘free will’ or ‘being able to do anything.’ It is interacting with a system that suggests possibilities through the representation of a fictional world and the presentation of a set of materials for action” (p. 7). Wardrip-Fruin et al draw attention to the relationship between player and machine in generating agency, considering player desires, dramatic probabilities and the ability to create satisfactory improvisational experiences. In other words, a game is not at the most agential when it allows the player to do exactly as they would like; rather, a game is at its most agential when a fine balance is struck between the game’s narrative, player expectations and the underlying computer system (among other things) enabling players to improvise the solution between their intended course of action to a backup course of action without too radically contradicting the internal fictions or revealing the underlying computation. Similarly, Ian Bogost’s idea of possibility spaces (Bogost, 2006, p. 69), it should be noted, focuses on actions as a result of restriction, with agency emerging from these restrictions in a manner strongly evocative of something like a reverse formulation of Gibsonian affordances. At the same time, ‘inter-reactivity’ in which both player and computer engage in mutual ‘reactions’ instead of a process of interaction (Smethurst & Craps, 2014) is also similar to and, arguably, an extension of Wardrip-Fruin et al’s work.

The explicitly ‘phenomenal’, in that Wardrip-Fruin et al identify agency as a phenomenon rather than an outcome of action, conception of agency is, to my mind, a step in the right direction for game studies. Throughout their paper, the almost posthuman acknowledgement of the role of the computer within the act of digital game play is also laudable. However, I want to suggest that this notion of agency, though seemingly distinct from just being the enacted will of the player, is nevertheless grounded in a traditional conception of the term; it does not break far enough away from the orthodox. For instance, the authors praise Far Cry 2 (2008), a first-person shooter game in which the player is able to plan actions before attempting to realise those actions. Should the player’s intentions go awry, through the use of a ‘buddy-system’ in which a non-player controlled character can rescue the player if in dire need, the player is able to seamlessly survive bungled combat, return to a short planning phase and try to execute a newly improvised plan based on a new situation, without having to be explicitly told that they have failed – i.e. through a ‘game over screen’ or ‘lost life’ (p. 7). This formulation of agency as a sufficiently competently programmed computer system (admittedly, no small task) and the presentation of materials for action is troubling; it suggests that agency is predominantly the ability of the designers of a computer system, and the hardware/software assemblage that eventually executes that design, to fool a human player into feeling sufficiently satisfied by their actions. Given the rich history of agency as a philosophical and social concept, this seems a rather shallow definition for the term, even within the scope of digital games. Wardrip-Fruin et al seem somewhat aware of this, given their clarification that although their approach could be viewed as derivative of Latour’s ‘actor network theory’, it is not, due to the distinct form of agency found in “fictional microworlds of games and other forms of playable media” (p. 8).

Wardrip-Fruin et al seek to assign the title of agency to what amounts to human input of variables into a looping digital system. One author at least has very recently taken up the task of challenging this system-centric vision of agency in digital games. Sarah Stang, writing in contrast to Murray’s framing of agency, but equally aware of Wardrip-Fruin’s formulation, contends that expressions of agency within a digital game can only ever be illusory (Stang, 2019). Stang argues that a true form of agency (or interactivity) is possible, however, and can be expressed by players engaging in discourse outside or beyond the game, such as with developers. In this way, players extend the reach of their actions beyond the scope of the game’s internal systems. Examples of this are evident such as when fans of a series use social media to influence developers into changing the narrative (as was the case in the Mass Effect series). While this is potentially problematic, not least because of the, possibly unintentional, rebirth of formalist authorial authority it implies, it nonetheless takes to task the notion that game scholars should be content with understanding agency as the expression of human-computer collaboration alone.

For my ends, both Wardrip-Fruin et al’s framing of agency and Stang’s rejection of it simply asks too little of digital games. In this paper I make the argument that – at the very least – an element of agency within the study of digital games should be the understanding that player actions are existential in nature; that player actions play a role in the co-constitutive existence of things. Agency, I will contend, should not be measured solely on the player’s satisfaction with the computer system’s upholding of the ludic/digital/narrative illusion, nor with the creators’ ability to effectively harness social media. Instead, the limits of agency should be understood as shaped by the extent to which player actions come to imbue matter with meaning, both within the game world and beyond. Admittedly there are few games that achieve this lofty height, but there are some and one, as I will explain below, is Return of the Obra Dinn. However, it is first essential to unpack exactly what it is I mean by imbuing matter with meaning.

Agential-realism and Agency in Games

Karen Barad writes of the “ongoing flow of agency” as both preceding and being productive of things; agency is the process “through which part of the world makes itself differentially intelligible to another part of the world and through which causal structures are stabilized and destabilized” (2007, p. 140). Perhaps most importantly, agency, “does not take place in space and time but happens in the making of spacetime itself” (2007, p. 140). Following Barad, it’s possible to adopt an understanding of agency as something other than the physical or social expression of a material being’s will; rather, agency can be understood as a decentralised phenomenon indicative of a wide array of forces producing the apparent materiality, and – where phenomenally possible – internal experience of subjects and object simultaneously. Though a concise account of Barad’s entire philosophy may not be possible here, it is helpful to see it as an alternative metaphysics, contrary to the subject-object dualism and representationalism common to Western philosophy. To Barad “we are of the universe – there is no inside, no outside. There is only intra-acting from within and as part of the world in its becoming” (2007).

As mentioned, the last few years has seen a handful of game studies scholars turn to Karen Barad’s agential-realism for a philosophical framework. Applying Barad’s decentralised notion of agency to digital game studies is an alluring possibility with the potential to disrupt conceptions of human players, fictional characters and the act of play itself. If we are not bound to seeing agency as actions and their implications but can instead embrace agency as the quality that enables the passing existence of things, a meaningful shift would occur in what game scholars consider an agential experience. Rather than placing an emphasis on what actions a game would allow a player to do, we could focus instead on what level of existence a game can allow a player to facilitate.

Janik rather masterfully summates Barad’s position regarding agency in classic game studies’ understandings, writing, “this also changes the status of agency, which is not something that actants have and can use, but rather a dynamic force that happens between them” (2017, p. 4). Janik writes, “In Barad’s ontoepistemological agential realism, intra-actions replace interaction, because there are no determined, independent entities preceding relations” (p. 4). What’s more, she stresses that “analysing the video game within this framework helps us understand how the game object and the player not only influence each other, but become partners in creating meanings” (p.7). Beyond this, Janik makes clear that there is much further to go in pushing just how disruptive to established thinking within both game studies and game design intra-activity and agential realism can be. By focusing on intra- rather than inter-actions, scholars “are not only creating analytic tools to better understand the relation between the player and the game object, [they] are also shifting our perception about play” (p. 7). I too desire to take up this disruptive stance; instead of suggesting that Barad’s work can be harmoniously integrated into game studies, I want to highlight the disruptive nature of Barad’s work as a basis for a philosophy of agency in narrative videogames.

Building on the good ‘Baradian’ work that has occurred to date within game studies, there is an aspect of Barad’s philosophy that is not currently common within writing on games: the explicit ethical and political dimension therein. While it is tempting to draw solely on the elements of their work querying concepts familiar to games and gaming (actants, agency) there is the possibility of something more rewarding that can come from attempting to carry over this social and political aspect as well. To Barad “we are of the universe – there is no inside, no outside. There is only intra-acting from within and as part of the world in its becoming” (2007, p. 396). Yet, contingent on this, agency is not just a question of being co-constitutively produced from the material universe; rather, it is the understanding that this universality brings with it an explicit responsibility to the world of which you are produced. If one rejects the existence of things as independent of, or ‘in’ the universe, it follows that one must assume that being ‘of’ the universe results in a constant, material – though perhaps imperceptible – impact upon that universe of which we are ‘of’.

An important final element of intra-active agency then, is the continued and active process with moral and ethical concerns. In Barad’s work, this process condenses materiality across vastly different scales along with the properties of materiality – the space and time it produces – into an entangled state where the microscopic, the personal, the universal, the past, present and future cease to be inert but rather become active political agents in subjective, social, national matters of life, death and everything in between. For instance, writing about the assemblage of nuclear matter and nuclear politics that spanned decades of Japanese culture, but came to a head in the Fukushima tragedy, Barad writes,

All these material-discursive phenomena are constituted through each other, each in specifically entangled ways. This is not a mere matter of things being connected across scales. Rather, matter itself in its very materiality is differentially constituted as an implosion/explosion: a superposition of all possible histories constituting each bit. The very stuff of the world is a matter of politics (Barad, 2017: p. G117).

This is what I am referring to when I mention the relevance of agency as the process through which material matter comes – not just to ‘matter’ – but to have meaning. It is possible, and – I think – necessary, for actions (not necessarily decisions) of players of games to have impacts on the outcome of not only play sessions, but also to extend outwards into the depths of history. While I’m not proposing this as an essential criteria for every game, I think it is an essential step for games to take if they are to be understood as an art form and, what is more, if understanding game agency is not to be limited to only the fictional or rule-based world of a game at hand.

To make the impact of actions clear, I think it is essential that a game strike the balance between player actions and universal outcomes. Few games have struck this balance well – many place the player in too essential a role; in a place where the course of history rests on their shoulders (the Assassin’s Creed series, for instance). In this position, players are given the opportunity to play with this digital mediation of history like a God, rather than simply being ‘of’ the world. I don’t believe it’s possible to really experience agency in this context as our actions take on an absurd quality. I think we know as humans that it is uncommon for one being to have so much power. It is for this reason that I want to turn to The Return of the Obra Dinn. Its balance of mundane gameplay with sweeping supernatural and ultimately complex social history fulfils a vision of Baradian agency extending throughout time and space in a political and ethical manner.

The Mystery of the Obra Dinn

Playing Pope’s nautical mystery game, one thing becomes clear quite quickly: very little is given back to players for their actions (at least, in the conventional sense of agency). Indeed, to paraphrase the declaration from the game that gives this paper its title, players are to take exactly what the game gives them and to expect nothing more. Return of the Obra Dinn tasks players with exploring the wrecked trading ship (or ‘East Indiaman’) in the year 1807 when it suddenly reappears in the docks at Falmouth, England, after it was mysteriously lost five years prior. Players must navigate through the ship that is increasingly open for exploration, attempting to uncover the circumstances that lead to the ship’s abandonment. To that end, players have at their disposal an enchanted pocket watch that allows them to observe the final moments of the deceased’s lives: on approaching one of the game’s many corpses, pressing the appropriate key on their keyboard or clicking the button on their mouse, players can listen to the last words (or, in some cases, sounds) of a crew member’s life, before they are given the chance to explore their last moment of life, in the form of a tableau, frozen in time. Players must use deductive reasoning to guess the names of the crew and clarify the circumstances of their death.

The ‘flashback’ – for lack of better word – that gives this paper its title occurs near the beginning of the game, and relays how Captain Robert Witterel lays waste to mutineers. When the mutineers exclaim that they intend to take the captain’s hidden treasure, Witterel retorts, “You bastards may take… exactly what I give you” before firing on and killing one William Hoscut, the ship’s first mate.

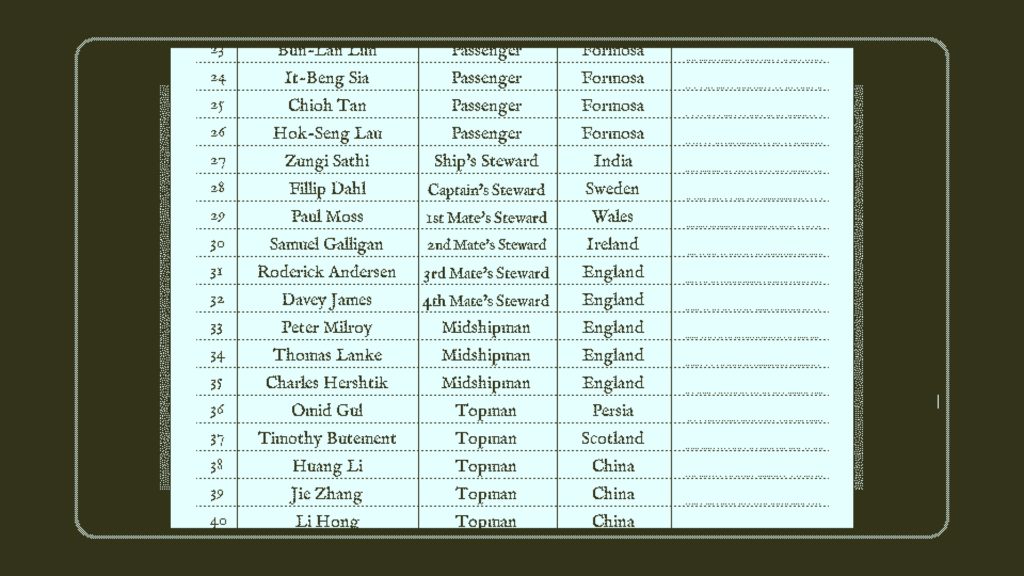

To someone who has not played the game, Obra Dinn may sound like an engaging adventure filled with murder and piracy. However, like Captain Witterell, the game also ‘gives’ players very little, and certainly not what one might have been expecting. Unlike in similarly nautically themed games, such as Assassin’s Creed IV: Black Flag (Kiekan, Guedson & Ishmail, 2013), Return of the Obra Dinn does not place players in control of another swashbuckling pirate, out to solve a mystery for treasure, love, or the pirate code; the player does not take part in sword fights, sailing ships, or any form of ‘pillaging’. Rather, in Obra Dinn, players take control of an East India Company inspector working within the insurance and claims office. Their motivation (the avatar is either male or female) for undertaking this enterprise is that they received a letter from their employer, asking them to carry out a full inspection of the ship (Image 1). It is only once they have boarded the ship that greater depth is given to their journey: the Chief Inspector has been given a book, presumably by their employer, that once belonged to the ship’s former surgeon Henry Evans. Inside the book, Evans includes a letter asking the Chief Inspector to investigate the mysterious circumstances surrounding the vessel before returning a completed account of the mystery to Evans in Morocco: the only mention of a reward of any kind is that if the player is able to complete the mystery they will learn the contents of a hidden chapter of the book.

Image 1: The call to action

Image 1: The call to action

Admittedly, there are many reasons why one might enjoy Obra Dinn: in order to ‘hook’ players, the game employs a remarkably distinctive aesthetic, achieved through the combination of high-definition audio recordings (including voice actors, ambient creaks and waves and period correct music) and, of course, the game’s unmistakable dot-matrix graphics filter. Beyond this, the core mechanic of using a ghostly pocket watch to engage in a literal form of ‘memento mortem’ – remembering death – by travelling into the mind’s eye of deceased crew members is evocative of a rich legacy of ghost stories and nautical lore. However, before long, players will come to realise that the seemingly banal motivation of an insurance assessment was not a ruse but is our intended purpose; players are restricted from intervening on the course of events or in affecting any change upon the world of the game. Instead of taking an active role in the story, the player must simply attempt to piece together an account of the relationships and actions that took place prior to the chronological beginning of the syuzhet, and fill in the blanks in the book they were given by Evans: for each death the player witnesses in a flashback, they must attempt to fathom who the person was, how they died and who killed them, using only the audio and tableau’s as sources of information. Players must use deductive reasoning to guess the names of the crew and clarify the circumstances of their death. On entering their guesses into the log book, players are told if they are either right or wrong, after every three guesses they make. Although some forms of death are so similar that it will not make much difference whether the player guesses that the deceased was ‘drowned by the beast’, ‘mauled by the beast’, ‘eaten by the beast’ etc. (all of these are considered ‘correct’ by the game), the player can only ever be correct or incorrect. The motivation of the avatar is not personal, they are not attempting to change the course of history – they are, quite simply, doing their job.

Those familiar with Lucas Pope’s previous game, Papers, Please (2013), an equally renown success, will know his distinctly unconventional design. In Papers, Please players take control of a border control officer in the fictional dictatorship of Arstotzka and must examine those wishing to cross the country’s border. Limiting the player’s freedom, placing them in a seemingly mundane, bureaucratic role within a world that is implied to be nuanced, complex, and full of autonomous actors with a range of motivations, provides an unusual spin on many game design doctrines. However, unlike Obra Dinn, in Papers, Please players have the distinct feeling that their actions – the decisions they make about the individual immigrants within the fictional world – are of increasing consequence, ultimately as a trigger for revolution or else further enforcement of the dictatorial regime. Jason Morrissette puts this in the following terms claiming the game “leverages its repetitious gameplay and bleak narrative to represent a debate that shapes the lives of millions of people around the world on a daily basis, whether the player chooses to bring glory to Arstotzka or risk it all for a better tomorrow” (Morrissette, 2017). There is no such engagement within Obra Dinn. The choices players make do not decide the fate of any of the characters onboard; they simply do or do not solve the mysteries presented by using the available clues, the outcome of which is minimal. There is a wonderful discord at play in Obra Dinn as players continue to evoke presumably ancient magic to transcend time and space in order to – anticlimactically – better estimate an insurance payout.

Agency on the Obra Dinn

On beginning the game after reading the intertitles that appear in the form of perfunctory letters outlining the mysterious nature of the Obra Dinn (a newspaper clipping describing that the “good ship Obra Dinn” is “lost at sea” and the orders from the Chief Inspector’s employers requesting an insurance assessment), the player is free to explore the ship. However, all that awaits the player is a corpse and two locked doors. The player can climb up and down a ladder leading to a small dinghy that brought the Chief Inspector to this location; they can wander freely for as much as they so choose; however, without further assistance, or some new means of expanding the space they find themselves in, the player is bound to these confines. Reflecting on Murray, Aarseth and Wardrip Fruin et al’s definitions of agency established earlier in the paper, we can read this opening state as an intentional disavowal of the tenets of agency as a convention of game design. Unlike Murray’s suggestions of what generates agency, there is an extremely limited number of player options and the impact of our choices is minimal – as established, our actions cannot change the history we see in any meaningful way; we are only permitted slight variations in how we record the past. Similarly, the objects, characters, setting and so forth of the game do not support the player in their activity as either Aarseth or Wardrip-Fruin et al. suggest they should. The game is very evidently a game and no new elements of the game will emerge to help a player through it should they get lost or stuck. When it is not being prompted to action by player engagement, the computer system is almost unnervingly inert.

It may seem trivial to focus on the initial setting of a game, when players are unable to do much of meaning. However, I want to frame this process, players initially discovering their boundaries on the ship, as itself a form of agency in Barad’s formulation of the term. Although players discover they are restricted, this act of discovery is an expression of co-constitution and agency on both sides of the player-system relationship. As the player exhausts their possibilities (contrary to Bogost’s notion of the possibility space) so too does the machine reinforce these limitations. Understanding this as agency requires a slight shift in mentality, away from notions of objects and distinct actors and towards a shared form of agency that is created prior to the becoming of apparent ‘things’. This form of discovery between player and machine is, in my mind, rather different from the collaboration suggested by Wardrip-Fruin et al. The computer system is not upholding the player’s expectations – it remains resolute. Rather, I think it is possible to see this process as analogous to the processes of scientific measurement, such as the labelling of photonic energy as either particle or wave, depending on the configuration of the measuring apparatus used. This kind of diffractive process, defined by Barad as an agential ‘cut’, can be read as a moment when “the apparatus enacts an agential cut – a resolution of the ontological indeterminacy – within the phenomenon” (p. 175). The players are not just exploring, they are ultimately involved in creating the Obra Dinn, in co-operation with their computer, Lucas Pope (and so on, and so on).

Of course, one might rightly assume that it would be possible to say this of many so-called ‘walking simulator’ games that share qualities with Obra Dinn. In restricting the ways in which players can act, a seemingly different focus must emerge from play. Indeed, Melissa Kagen (2018) suggests that walking sims “force a player into relative passivity, a state at odds with the interactive agency prized in videogame design”. However, there is a reason for my choosing Obra Dinn over Myst (Cyan, 1993), Journey (thatgamecompany, 2012) or The Stanley Parable (Galactic Cafe, 2013) to name but a few. Put simply, there is a unique quality to Obra Dinn that caught my attention – the fusion of seemingly meaningless actions with the production of a wide-reaching impact. This is not a common quality within many walking simulators. Within Myst, for instance, the player is not simply a hapless insurance investigator whose actions have no bearing on the game world – rather, the anonymous stranger the player inhabits comes to play an essential role in the resolution of the game’s plot as they must either become captive on the mysterious island or enable the escape of one of the game’s central characters. Similarly, Bo Ruberg (2019) has pointed out the restrictive nature of the game play as many of these games limit the potential impact of their narratives. In their paper on Gone Home, for instance, Ruberg reflects on how the game’s straight paths restrict the potential for queer play and reflect the underlying normativity of the game itself. Obra Dinn, by comparison, seems purposefully designed to prevent the creation of linear paths and even allows several different possibilities in the recounting of the various crew members’ fates.

This is not to say the quality I identify in Obra Dinn is entirely unique to it. The Stanley Parable, for instance, can be read in wonderfully illuminating ways and Kagen’s article on Firewatch draws attention to a positive example of a form of ‘queering’ that is achieved through walking simulator design. Indeed, Firewatch could have been used to make a similar point to the one I am attempting to make here: it similarly restricts the actions a player can take (“There’s a reason it’s called Firewatch and not Firefight” Kagen writes) but – counter-intuitively – in doing so, it says a great deal about the cultural-political surrounding context of the game. In being relegated to watching, rather than fighting, the game – Kagen argues – critiques the concept of hyper-masculinity that is so popular throughout digital gaming as a medium. This is an excellent example of the kind of ‘agency’ that I think we can identify within games; however, I have chosen Obra Dinn for its specific, explicit, far reaching commentary on global political and historical contexts, as well as for its supernatural elements suggesting a kind of boundless agency, extending even beyond the comments on gender and culture suggested by Firewatch.

Given then the almost unique appeal of Obra Dinn, its uniquely limited-yet-impactful agency and the fundamental insignificance of our character on the game world, I want to return to how agency is removed from the player or even from the digital actors (following Barad, “in an agential realist account, agency is cut loose from its traditional humanist orbit” (p. 177)) and recast as preceding ‘things’, giving rise to phenomena that produce apparent things. As I have highlighted, when exploration of the Obra Dinn is accepted in this intra-active manner, the core gameplay loop becomes a process matter making.

However, while exploring the empty ship can be understood as a form of ‘spacetimemattering’ in Barad’s terminology, of co-constitutively making the ship in material terms, I believe that as the game progresses, this matter-making becomes a process of meaning-making. This starts small at first: perhaps even in the first time players are exposed to the concept of ‘Obra Dinn’ (a strange and exotic sounding concept to a native English speaker), the title of the game. Players then further generate semiotic constructions of the phrase when exposed to the game’s landing page that shows a simple graphic of the titular ship drifting in a vast ocean. Players then read about the ship in the brief snippets before finally being able to construct their own specific reality of the ship itself by exploring it. It is not simply that we create a ship, we understand that this is a ship within the specific lineage of the British East India company at the height of the colonial 19th century, whose journey was set to begin from England, to continue through Europe and on to the continent of Africa. The game’s title is evocative of the orientalism of the time where “othered” human cultures stirred almost otherworldly fascination – but also as the “set of structures inherited from the past, secularised, redisposed and reformed” in the orientalism that continues to inform the processes through which global politics are conducted today (Said, 1978, p. 122).

This initial invitation to begin imbuing the late crew of the ship with meaning is reinforced through the early interpersonal dynamics of the first few characters that we discover. Indeed, the first four deaths that we witness – internally, the events of the final chapter of the found book – are three mutineers murdered by the ship’s captain, and then the captain himself as he commits suicide, after apologising to the body of his wife, Abigail, for having shot her brother. The relationships players engage with here are not entirely out of the ordinary for a nautical adventure. Yet the player’s role in this is, seemingly, entirely inconsequential. We simply witness these acts and do our best to extract and quantify data from this interpersonal human drama. To an extent, we can view this dispassionate engagement with events as something akin to Arendt’s banality of evil 1: the player chooses to continue passively allowing these murderous events to unfold in service of some greater abstract ideal, bureaucratically cataloguing the details. However, there is another way to view these formative events. This exploration of the crew’s narrative can be fruitfully viewed as akin to the physical exploration of the ship. However, distinct from how our exploration reveals the material becoming of the ship, unveiling its hidden physical dimensions through our continued searching, this new form of exploration fills the ship’s materiality with meaning. We are still engaged in the process of uncovering, but now we are configuring materiality to give rise to intricate human narratives. This is as clear a depiction of the process of Barad’s agency as I can imagine one could hope to draw from digital gaming. The history and events of the ship and its crew are all always already contained within the vessel. Through the use of our cutting apparatus – our ghostly stopwatch, a proxy to the two-slit experiment or electron microscope – we engage in the reconfiguration of reality, unveiling various levels of the sediment of history, out of joint but each undeniably real within the context of the game.

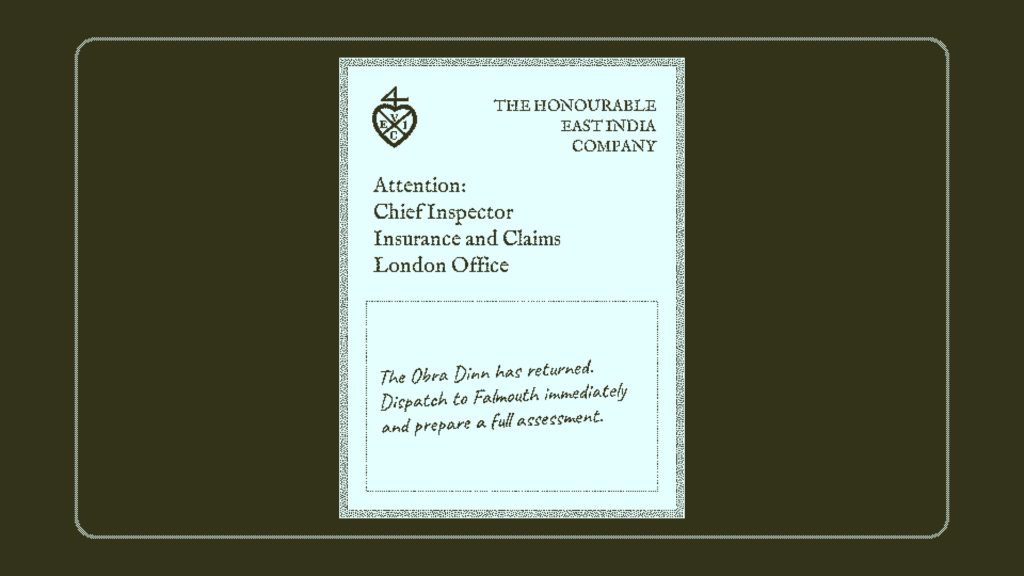

The second element of Obra Dinn that I want to draw attention to is a form of agency that is illusive and troubling: that of the role of the unknown. Most superficially, it takes the form of the various monsters throughout the game that confront the player with their horrific shapes and are the active cause of death for many of the crew. Their agency, however, is entangled with the player’s – although we can read the supernatural creatures as, perhaps, acting on behalf of the ocean or the essentialist ‘natural’ non-human, it should be clear by now that there is no need for a metaphorical actor on the part of the nonhuman when playing a game – as Wardrip-Fruin et al point out, we are constantly engaging with our non-human other when playing digital games. Both human and machine are understood being equally produced and defined through the act of play within the agential realist framework. For this reason, I am tempted to read the inclusion of the supernatural within Obra Dinn as something of a red herring. Directly following the death of the ship’s captain, early in the game, we see that the majority of the ship’s crew lost their lives at the hands of a giant kraken (the cover image of this paper). While this gives the plot of the game a certain lift, I think it also attempts to pull the player away from the more powerfully evocative forms of agency in the game. It is tempting to see the kraken as exemplary of the forms of classic agency given its ability to exact its will. However, there is a limit to how much the agency of the imagined non-human can reverberate through the material history that otherwise shapes the game. This irony is present in the game as although the memories in which in the kraken tears apart various crew members are initially terrifying, players will soon realise that they are not in any danger. They are as free to explore these memories as any others. The actions of the kraken, mermaids and crab-mounted others of the game are ultimately as consequential to the lives of the crew as the rocking of the boat, or the influence of sickness and poor sanitation.

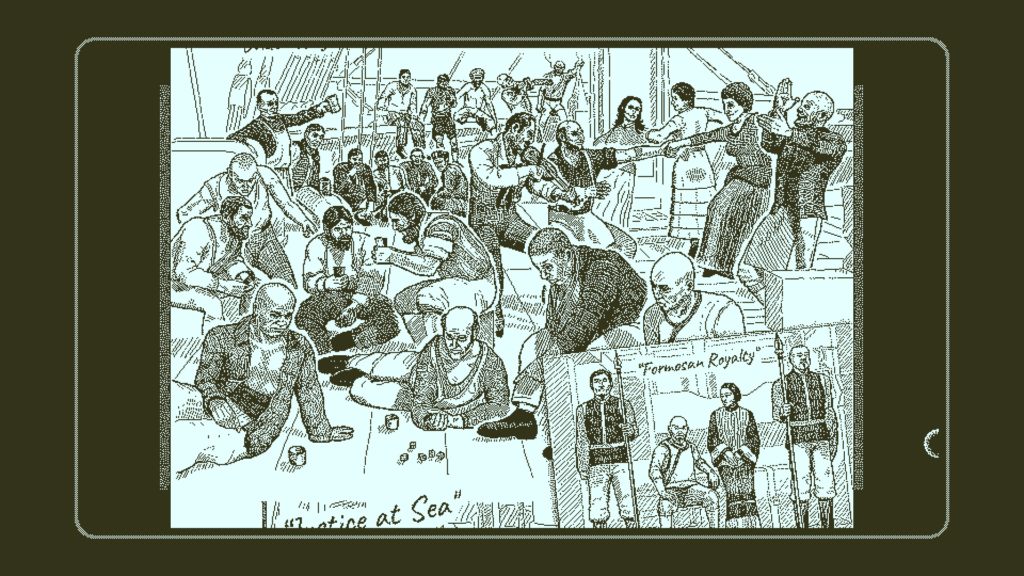

The third, and key method, by which Obra Dinn goes beyond a passing resemblance with Barad’s theories is how it stretches the implications of events throughout time and space by entangling the player in social and racial orders. Throughout the game players identify the crew based on the flashbacks they see, but also by using three depictions of the crew (image 2) and a list of their names (image 3). Although much of the drama of Obra Dinn revolves around the inclusion of supernatural elements (murderous mermaids, giant crab riders and even a monstrous kraken) rather than setting the mystery in a fictional sea, in a fictional time and therefore at a remove from human history, Pope instead embraces the complexities of human history and culture and attempts to entangle it into these supernatural elements. The crew, as you can see from the crew list, is composed of many nations and races. However, this is not done simply as an empty gesture. The crew of Obra Dinn share the racial and political tensions one would expect of the early 19th century. Indeed, even the colonial title of Taiwan as ‘Formosa’ is heavily present in the crew list.

Image 2. The engraving of the crew

Image 2. The engraving of the crew

Image 3. The crew’s manifest.

Throughout the game, we slowly discover that it is the racial and class-driven tensions between crew and passengers that stoke much of the tragedy that befalls the Obra Dinn. In an early chapter of the book, but one that is uncovered quite late in the game, players witness the murder of Nunzio Pasqua, the sole Italian passenger on board, at the hands of the English second mate, Edward Nichols. The race of these characters is important here, as Nichols murders Pasqua to cover up his own attempted theft of the ‘Formosan’ treasure. Nichols is aware that the crew on board will not question his assertion that Pasqua, an Italian, was murdered by Hok-Seng Lau, the Formosan passenger. This plays out exactly as he expects, as Lau is subsequently executed. However, this only initiates the chain of events that leads to the downfall of the ship. I find there to be direct parallels here with Barad’s writing on the ‘haunting’ of the Japanese Fukushima nuclear disaster. They assert that past events linger but that they are not immaterial; rather, the very material forces of nationalism, racism, global capitalism, resource management etc. are all entangled into the geopolitical machinations that must be navigated in the wake of such an event.

The player must similarly navigate a condensed form of time in Obra Dinn and continue to reify the troubled, entangled histories of the crew of the vessel. The Obra Dinn itself ceases to be merely a means of transportation but becomes a locus of the flux of human activity and agency amidst the swelling industrial and trade revolution that the East India Company was so instrumentally a part of. The violence witnessed here against East Asian passengers is no coincidence, given the rising threat of the opium wars on the near political horizon of the time period in which the game is set. As the player has no choice but to continually delve into the past and uncover more examples of dehumanising treatment, witnessing man’s inhumanity to man, it is difficult not to feel enveloped in the interweaving agencies of the crew members that we are, along with the machine, Pope (etc.), bringing into being, alongside the troubled imaginaries of histories of trade and colonialism that are similarly entangled with a player’s activity as a participant in this game as co-constitutive performance.

Embracing Obra Dinn as a lesson in new design experience suggests the need to move past the idea of agency as the property of independent things existing concretely within the world; instead, we can embrace the notion of apparent things only ever passingly brought forth, diffractively, through a host of universal processes. This is evident not only in the becoming through co-constitution discussed first, but also in a broader sense: the world of Obra Dinn can be understood as a complex history of entangled events, constantly coming into being. Becoming is not a matter of one entity becoming whole, but rather a chronology, an order, an existence, constantly in emergence. The world that is created is not fictional, not within our grasp or our control and yet we are part of it.

Conclusion

In this paper, I have proposed a new form of agency that is not dependent on the provision of meaningful actions for the player; greater or lesser agency is, instead, resultant from the perception of agency as a shared phenomenon that produces both the player and the virtual world they are engaging with. Obra Dinn feels like an intensely engaging experience – not because the player can make a meaningful impact upon the game world, but because the player cannot help but become sensate of the immense agency that enables the game’s world, but also its comments on real world colonialism, and the player’s place within these. What makes Obra Dinn so important for understanding this as a theory for agency is that the player is, functionally, almost entirely removed from the agency of the other actors within the game. The player cannot affect the particular history of others, and the other actors within the game cannot affect the history of the player. Yet, without the player, the histories of the characters will not unfold and the entangled web of actions and interactions between them and the world in which the game is set (a magical realist interpretation of the colonial history of the British Empire) will not emerge. I have argued that the player of Obra Dinn does not ‘have’ agency but, rather, is a part of the co-constitution of agency. Yet, this feeling of being a part of the becoming of the world, is just as rewarding as saving the world.

It is a natural conclusion to presume players have limited agency if they do not appear to be able to impact a game world in obvious ways; yet games like Return of the Obra Dinn are tremendously rewarding experiences. I suggest then, that it is perhaps our concept of agency that is flawed. In this paper, I tested the boundaries of using agential realism to discuss agency and interactivity by exploring a game that limits player agency and proposes a new intra-activity. In contrast to what we might think given Murray, Aarseth and Stang’s understandings of agency, I argue that Obra Dinn is an immensely agential experience so long as we understand agency in a distributed manner. Of course, Obra Dinn is just one game and much more work must be done to continue testing the legitimacy of this theory. However, I suggest that if agency in games is not understood as our capacity to impact on the game world, but rather as the mode through which things come to be, in accordance to Barad’s philosophy, we can envisage our actions as akin to the ebb and flow of agency as a fundamental part of the universe. This could represent a complete overhaul in how developers and players approach game design and play. If players and designers were to focus on games as the processes of creating worlds and phenomena that enable players to feel engaged in world-making processes, this would open the floor to new ideas for design, narrative and inter(intra)activity.

References

Aarseth, E. (2012). A Narrative Theory of Games. FDG, 12. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/254006015

Arendt, H. & Baer, P. (2003). The Portable Hannah Arendt. London: Penguin Classics.

Banks, J. (2015). Object, Me, Symbiote, Other: A Social Typology of Player-Avatar Relationships. First Monday, 20. Retrieved from https://journals.uic.edu/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/5433/4208

Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Barad, K. (2017). No Small Matter: Mushroom Clouds, Ecologies of Nothingness, and Strange Topologies of Spacetimemattering. In A. Tsing (Ed.) Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet. (pp. G103-G120) Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Bogost, I. (2006). Unit Operations: An Approach to Videogame Criticism. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chang, A. (2017). Green Computer and Video Games: An Introduction. Ecozon@, 8, pp.1-17.

Kagen, M. (2018). Walking, Talking and Playing with Masculinities in Firewatch. Game Studies, 18. Retrieved from http://gamestudies.org/1802/articles/kagen

Keogh, B. (2018). A Play of Bodies: How We Perceive Videogames. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Janik, J. (2018). Game/r – Play/er – Bio-Object. Exploring posthuman values in video game research. Proceedings of The Philosophy of Computer Games Conference , 1.pp 1-8. Retrieved from http://gamephilosophy.org/wp-content/uploads/confmanuscripts/pcg2018/Janik%20-%202018%20-%20Gamer%20player%20bioobject.pdf

Leorke, D. & Wood, C. (2019). Alternative Ways of Being: Reimagining Locative Media Materiality through Speculative Fiction and Design. Media Theory. Retrieved from http://mediatheoryjournal.org/leorke-wood-alternative-ways-of-being/

McKeown, C. (2018). Playing with materiality: an agential-realist reading of SethBling’s Super Mario World code-injection. Information, Communication and Society, 9, pp.1234-1245.

McKeown, C. (2019). Reappraising Braid After a Quantum Theory of Time. Philosophies. 4(4), 55. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies4040055

Morrissette, J. J. (2017). Glory to Arstotzka: Morality, Rationality, and the Iron Cage of Bureaucracy in Papers, Please. Game Studies, 17. Retrieved from http://gamestudies.org/1701/articles/morrissette

Murray, J. H. (2016). Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace (2nd, updated ed.). NY: Free Press.

Ruberg, B (2019). Straight Paths Through Queer Walking Simulators: Wandering on Rails and Speedrunning in Gone Home. Games and Culture: A Journal of Interactive Media, pp 1-21. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412019826746

Smethurst, T., & Craps, S. (2015). Playing with Trauma: Interreactivity, Empathy, and Complicity in The Walking Dead Video Game. Games and Culture: A Journal of Interactive Media, 10.3, pp 269-90.

Stang, S. (2019). “This Action Will Have Consequences”: Interactivity and Player Agency. Game Studies, 19. Retrieved from http://gamestudies.org/1901/articles/stang

Stangneth, B (2014). Eichmann Before Jerusalem: The Unexamined Life of a Mass Murderer. NY: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.

Said, E. (1978). Orientalism. NY, Pantheon Books.

Stone, K. (2018). Time and Reparative Game Design: Queerness, Disability, and Affect. Game Studies. Retrieved from: http://gamestudies.org/1803/articles/stone

Wilde, P. & Evans, A. (2017). Empathy at play: Embodying posthuman subjectivities in gaming. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, pp 1-16.

Wardrip-Fruin, N., Mateas, M., Dow, S. & Serdar Sali (2009). Agency Reconsidered. Breaking New Ground: Innovation in Games, Play, Practice and Theory. Proceedings of DiGRA 2009, pp 1-9. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242580451

Ludography

Undertale, Toby Fox, US, 2015.

Assassin’s Creed IV: Black Flag, Ubisoft Montreal, Canada, 2013.

Firewatch, Campo Santo, US, 2016.

Gone Home, The Fullbright Company, US, 2013.

Myst, Cyan Worlds, US, 1993.

Journey, Thatgamecompany, US, 2012.

The Stanley Parable, Galactic Café, US, 2011.

Mass Effect series, Bioware, Canada, 2007-2017.

Minecraft, Mojang, Microsoft Studios and Sony Computer Entertainment, Swedan, 2011.

Pokémon: Let’s Go, Game Freak and Nintendo, Japan, 2018.

Papers, Please, 3909, US, 2013

Return of the Obra Dinn, 3909 and Warped Digital, US/UK, 2018.

Author’s Info

Conor McKeown

King’s College London

conor.mckeown@kcl.ac.uk

- Hannah Arendt’s theory of the “word-and-thought-defying banality of the evil” (2003, p. 365) was the product of her observations of the trial and execution of Nazi war criminal Otto Adolf Eichmann whose actions in the Second World War included creating lists and statistics that helped facilitate the deportation of hundreds of thousands of Jewish people from Germany and eventually personally overseeing the Final Solution or mass executions of over 437,000 Jews in Hungary. Arendt’s theory, broadly speaking, can be understood as the role of bureaucracy in dehumanising and facilitating genocide and other criminal acts. Eichmann is framed by Arendt as a participant in and facilitator of this evil, portrayed as more interested in efficiency and facilitation of institutional actions than the ideology behind them. His actions are detailed but with an emphasis on the forms he made Jews sign; forms that semi-legalised their own executions, enabled their belongings to be legally subsumed into the Nazi government and account for their movements and numbers. She notes that “as far as Eichmann could see, no one protested, no one refused to co-operate” (p. 346). Reflecting on the his personality, she describes Eichmann as the kind of person “who never made a decision on his own, who was extremely careful always to be covered by orders, who—as freely given testimony from practically all the people who had worked with him confirmed—did not even like to volunteer suggestions and always required ‘directives’” (p. 329). It is even noted that Eichmann made a failed attempt to send many of the Jewish prisoners to a camp in Lódz where preparations for execution were not yet complete. However, Eichmann – Arendt informs us – took the view of this situation “that he had not disobeyed an order but only taken advantage of a ‘choice’”. Arendt later clarifies that “what he fervently believed in up to the end was success, the chief standard of ‘good society’ as he knew it” (p. 355). Although Arendt’s portrayal of Eichmann has been heavily criticised with some contending that Eichmann was an ideologically devoted Nazi (Stangneth, 2014), the theory is still of great importance for understanding agency, particularly the kind of compliant agency that is encouraged by digital games. Reflecting on Obra Dinn we investigate the deaths of each member of the crew but never attempt to use our time travelling powers to intervene in these deaths. Our interest, reminiscent of Eichmann’s reliance on forms as Ardent portrayed him, is in completing the paperwork behind the deaths of the many crew-members of the boat, perhaps motivated by some ill-defined promise of that “good society” of the East India Company and our mysterious benefactor that have tasked us with authority. ▲

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.